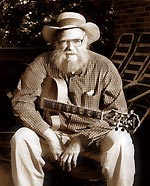

Page Stephens

"Better One-Handed Than Most Guitar Players Put Together"

When Page Stephens isn't debunking, he's plunking. On the guitar, that is.

His interest goes back to his Wabash days, when he helped found the Wabash Folksong Club, which brought to campus some of the leading folk and guitar acts of the 1960s, including the powerful Delta blues man Son House and folk music legend Doc Watson.

But his real guitar hero is his fellow Wabash alumnus, Amos Garrett '64. Garrett attended the College for two years before diving into the music world full-time, playing with Ian and Sylvia Tyson's The Great Speckled Bird, one of the first country rock groups that changed the direction of pop music.

"Amos and I were both Kappa Sigs, and the first time I heard him play his guitar -- an old Goya flat top which he probably has forgotten he ever owned -- I learned that there was much more to playing the guitar than I ever realized," Stephens says.

If you were anywhere near a radio in the '70s, you probably remember Garrett for the famous guitar break on Maria Muldaur's "Midnight at the Oasis," and he's since recorded with more than 150 other artists, including Jesse Winchester, Stevie Wonder, Emmylou Harris, and Bonnie Raitt.

Garrett now makes his home in Turner Valley, Alberta, and tours with his band in the U.S. and the U.K. and has a large and loyal following in Canada.

"The reason that Garrett's name floats along the periphery of pop music instead of the front lines is because Garrett eschewed mainstream rock to make consistently interesting music," a writer for Scene Magazine wrote earlier this year. Guitar Player calls Garrett "one of the most lyrical and original guitarists playing today."

Page suggests you check out Garrett's web site.

Magazine

Summer/Fall 2002

A Skeptical View

of the Skeptic

Think devils in the door and psychic prophecies are anything other than

coincidence? Page Stephens ’65—and a million dollars—say

“You’re on!”

By Erik W. Dafforn

’91

It was

like a scene from William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist...almost. A

house with a young girl. An evil presence terrorizing her. An exhausted,

desperate family soliciting experts to rid the house of wickedness and

restore order and sanity to their lives.

Here, though, is where the similarities end. The young girl’s soul

had not been the target of the possession. Instead, she said, evil had

taken aim at her new bedroom door. The devil, or at least his image, lay

in the wood grain itself, and it was giving her the creeps.

In this less-than-chilling adaptation of the tale, the would-be exorcist

was not a young cleric—far from it. Page Stephens ’65, one of

the men called in to deal with the devil in the door, would look more

at home on stage with ZZ Top than in the priesthood. The girl’s parents,

trying to assuage their daughter’s fears, called Stephens, along

with his friend Rick Rickards. Even over the phone, Page had a pretty

good idea what he would find when he arrived, and he was right. The door

was a “split veneer’ type: Hewn of a thick plank of wood sliced

along the plane, the door’s left and right sides were mirror images.

This random configuration created a symmetric design on the door that

the girl mistook for the image of Satan.

Not that it wasn’t an interesting coincidence.

“It was a gorgeous devil, believe me,” Page recalls. “Horns,

a gaping mouth,” he trails off, then charges back with an unapologetic

summary: In his experience, the truth behind most paranormal events is

adolescent fantasy.

Page Stephens, a dyed-in-the-wool, part-time debunker of the paranormal,

full-time adversary of absurdity, and would-be blues guitar sensation,

graduated from Wabash with a history degree and entered the Ph.D. program

in anthropology at the University of Illinois. “I decided,’

he reflects, “that history did not give me enough insight into the

nature of human thought.” He then took his doctorate to Cleveland

State University to teach in its anthropology department.

Gaining his doctorate and even teaching anthropology for years didn’t

seem to quench Page’s thirst for the elusive “nature of human

thought.” Beyond his anthropological studies, nearly two decades

ago he co-founded Cleveland’s South Shore Skeptics, an organization

“dedicated to science education and the investigation of paranormal

and pseudoscientific claims.” Health concerns forced his departure

from administrative duties a few years ago, but he’s better now,

and he still maintains close contact with the group.

Opinions vary on the origin of Page’s skeptical roots, Professor

Joe O’Rourke, however, offers some perspective, describing events

from when Page was a student at Wabash almost 40 years ago: “I recall

during a snowfall, he backed [his car] into the middle of street and killed

the engine. Skeptical of his ability to start the car, he simply abandoned

it and set off on foot for class. The car sat there most of the day as

I recall, creating a permanent detour.”

In addition to his own South Shore Skeptics, Page deals regularly with

the James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF), a non-profit group that

attempts to promote critical thinking by disseminating “reliable

information about paranormal and supernatural ideas so widespread in our

society.” Like Page, the JREF doesn’t mind claims—only

claims without proof. As a result, the organization has an ongoing challenge

to the public, offering a cool one million dollars “to anyone who

can show, under proper observing conditions, evidence of any paranormal,

supernatural, or occult power or event.” Setting a good example for

other promising skeptics, Page is responsible for $2000 of that million

in the event of anyone winning the challenge.

Budding spoonbenders and alchemists, however, should take special note

about the “One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge.” At the

bottom of the application rests an understated warning: “Please be

advised that several claimants have suffered great personal embarrassment

after failing these tests.”

A 1999 article in Cleveland Scene supports that advice. In the article,

Jacqueline Marino tells the tale of “Mr. Blau,” a curiously

pseudonymous, self-diagnosed telepath in his late fifties who claims to

have been on the sending end of psychic messages since he was a teenager.

The JREF works with local skeptics groups to run preliminary tests and

works as a filter for the million dollar challenge, and Mr. Blau appeared

before Page Stephens and the rest of the South Shore Skeptics to prove

his talent and take a step toward claiming the prize. Unfortunately for

Mr. Blau, it didn’t work out quite the way he hoped.

The test was set up so that Mr. Blau would be able to implant a thought

into a “receiver”—an eager and hopeful volunteer from the

South Shore Skeptics. Coin tosses, seen only by Mr. Blau and the testers,

would determine whether Mr. Blau would mentally “touch” the

receiver on his left or right shoulder, after which—if the receiver

actually perceived the message, he would raise that hand. Out of 100 coin

tosses, Mr. Blau needed to correctly convey 66 to his receiver to pass

the test and be sent on for further testing by Randi and others at the

JREF.

He got 48. “Essentially,” Page says, “it came out slightly

below chance.”

Were Mr. Blau and his receiver happy with that score? “Well, they

accepted it,” Page recalls, as if they had a choice.

“Debunker’ is a contentious term with which many skeptics find

themselves labeled. “We’re looking for any outcome we get,”

Page says, noting that their only agenda is uncovering the truth, whatever

it is. They’re not out to prove, specifically, that anything doesn’t

exist; they just want its existence proven scientifically. According to

Page, numbers aren’t as conclusive as people would like to think,

so third-party evaluations, like those carried out by the South Shore

Skeptics, are necessary. “I could make up a test that would give

me whatever result I want. We do it honestly.”

Still, within his group he uses the term “debunker” with a sort

of defiant pride. “They don’t like it, but I tend to use it

anyway.” After all, he asserts simply, “if there’s bunk

out there, what do you do? You de-bunk it.”

Page doesn’t limit his debunking to official South Shore Skeptic

meetings, or even to normal waking hours. One night, his wife, Penny,

had an asthma attack and needed Page to take her to the emergency room.

Fortunately, the ER had been empty nearly all that night, and the doctor

saw her quickly. As she received her treatment, Page found himself with

some idle time and decided to discuss with the staff a matter of socio-medicinal

lore that had plagued him for some time.

“Is it really true,” he asked, “that when the moon is full,

the emergency room is packed full of wild cases?”

“Oh, yes,” they all agreed, adding clichés about full

moons and their ability to bring out weirdoes en masse. When Page was

satisfied that they had achieved consensus, he asked, “Have any of

you looked outside lately?”

Apparently none of them had, because they would have noticed that on that

particular night the moon was full, yet the emergency room, except for

Page and his wife, was totally vacant.

With the exception of impromptu occasions like the emergency room, Page

rarely challenges others’ beliefs on their own turf. You won’t

see him, for example, interrupting a church sermon or pulling the beard

from a department store Santa Claus. “I don’t pay much attention

to religion, oddly enough. I’m just not religious. I don’t dislike

people who are religious.” He steps in only when he believes that

people—either individually or collectively—could be hurt by

believing something he feels is dangerous.

He does get a bit defensive, however, when backed into a corner. When

learning of his skeptical nature, people routinely and sternly ask him

whether he’s an atheist, with surprising results. “‘No,

I’m not an atheist,’ I tell them, ‘I’m not an a-Santa

Clausist, not an a-Easter Bunnyist either.’”

Quoting his pal Rick Rickards, Page believes that “you can never

define yourself in terms of things you don’t believe in. There are

billions of things out there that I don’t believe in; it would take

me forever to say ‘I’m an a-this, and I’m and a-that.”

So why do people insist on believing things when objective testing—or

even a little informal observation—would prove them false? Why does

so much of society have a strange and devoted attachment to believing

things belied by logic?

“Don’t ask me,” Page laughs. “I haven’t figured

that out yet. I quit trying.”

It’s probably frustrating to guys like Page that astrology is more

popular than ever. Psychics have tremendous mass-market appeal, regularly

appearing on talk shows such as “Larry King Live” and “The

Montel Williams Show.” Opportunistic fortune-tellers, despite occasional

wranglings with attorneys general and disclaimers decrying “for entertainment

use only,” continue to thrive on late-night television and the Internet.

Despite the efforts of Stephens, the South Shore Skeptics, the JREF, and

other like-minded individuals and organizations, it’s not clear that

reason is winning the battle.

But it’s not about winning, at least to Page. He learned long ago

that even when presented with facts that refute certain concepts, many

people just don’t care. Regarding the ability of skeptics to convince

people or at least get them to think, he seems resigned.

“I don’t know what our conversion rate is,” he laments.

“I’d hate to guess.”

On its surface, his answer is benignly humorous; at its depths, it offers

a glimpse into how deeply his philosophy has infiltrated his personality.

He really would hate to guess, because his guess might not stand up to

the analysis that he would demand of a concrete answer. When asked what

his mentors at Wabash—icons such as Eric Dean, Norman Moore, Paul

McKinney, and Joe O’Rourke—might think of his pursuits, he replies

with a dogged “you’d have to ask them.”

Page often meets simple questions head-on with replies that begin “I

have no idea...” or “There’s no way to know...”—questions

that beg only the mildest form of speculation or guesswork. True, this

seems unlikely coming from a man whose novella-length rants on the Wally-L

email list have caused more than one alumnus to concede his point rather

than admit he hasn’t read Page’s whole argument.

So what’s next for Page? How long will he keep up the challenge?

How far must the next dogma peddler run to escape his wrath?

We’d hate to guess.

What

are your thoughts?

Click

here to submit feedback on this story.

Return to the table of contents