CLICK TO ENLARGE

"Within those smoke stained walls, it occurred to me that the first stories I heard were not Salinger or Kerouac, certainly not Thackeray or Dickens, but were stories that were told with an elbow on a truck bed, one leg crossed behind the other and boot pointed toe down into the gravel."

Magazine

Summer/Fall 2002

Unlikely Haven

It was just supposed to be a photography assignment, but when he chose

the local “biker bar” as his “cultural geography project,”

Kyle Nickel found unexpected friends who reminded him of where stories

live, and why they matter

By Kyle August Nickel

'03

nickelk@wabash.edu

We Wabash

men who still run our hands on the smooth banisters of Center Hall, who

walk beneath the old limbs of the arboretum so many times a week that

we take them for granted, who do not yet have lamb skins on our walls,

we are prone to delusions of grandeur. Those who have gone before us have

left a legacy of professional success. Our inheritance is an expectation

of greatness, and I am no less of a calculated dreamer than any of my

classmates. So it was odd for me to find this place, this unlikely haven.

It was just supposed to be a photography project. Get in, get the shots,

and get out without having my Wally skull beat into the bar. The first

trip I made to this place I wasn't certain of achieving anything more

than getting in. I went back, and went back again, and eventually, I found

a table to call my own and people remembered my name. I was no longer

an imposing photographer, but a guy who happened to take pictures. In

the absence of the uncertainty and suspicion my camera first caused, a

wonderful thing happened: people told me stories.

I sat alone sometimes. The bartender, Davey, walked by and said, “Sittin’

with all your friends are you?” I smiled and he laughed as he slapped

me on the back. I stared off into the smoke stained murals of Canadian

wilderness painted on the walls and listened as folks sat down with me

for a minute to say hello.

Lil’ Bit quit her job, was selling her house, and moving to Arizona.

Bob rode his horse into town that morning and hitched her up to the dumpster

right outside the back door.

Coxy was telling someone “You just tell that girl of yours that school

is her job.”

Les showed me a trick with the matchbook on the table and tells me there

is no better way to travel than in a boxcar.

And more often than not, the stories turned to motorcycles. Who wrecked,

who bought, who sold, where, when, and all the adventures the highway

gives up, all told and retold with beautiful passion.

If I could, I'd tell you that on Friday nights we all mount up on our

Harleys, that we are rouges and knaves and I wear black leather chaps

worn thin from a thousand open road miles and broken beer bottles. I'd

tell you that one time; the boys and me blew off work for a whole week

and rode out to Mesa Verde to drink whiskey with the rattlesnakes under

the stars. I'd tell you it meant something when Coxy called me "brother."

I'd tell you I fit in. The truth is, if this is Easy Rider, I'm Jack Nicholson,

a wannabe.

At some point I realized that the soil beneath my fingernails was different

from the oil and grease beneath their own. These people have steel beam

bones, high-octane blood and unstoppable V-8 four barrel hearts that beat

on and on and on. I have creek water in my veins, a skeleton of hickory.

My clock is set to sowing and harvest and I am certain I don’t have

the strength to re-set it to shifts. Maybe farmers and factory workers

are not so different. We don’t dissect our stories.

Within those smoke stained walls, it occurred to me that the first stories

I heard were not Salinger or Kerouac, certainly not Thackeray or Dickens,

but were stories that were told with an elbow on a truck bed, one leg

crossed behind the other and boot pointed toe down into the gravel. The

tales I love most are not printed anywhere, but linger in some ghostly

memory of a hay wagon or canoe, are still being told in the cattle barns

and open pastures of my childhood. There is no adequate means to retell

the tales I heard in this place. The laughter at just a certain moment,

the pause to light a cigarette a sentence before the conclusion, the lips,

the voice, the face of the teller, there are no keys on the computer for

these things. There are photographs.

Wild Bill looked over at me and fixed his stare. I didn’t know him

yet then. This is before I know he is completely mad, homeless, former

prisoner, gold miner, lumber jack, magician, before our long talks of

East Africa and British imperialism, before he recalled the Kant and Spinoza

he read in prison, before he talked to trees and rocks and other things

of mother Earth. He was just bright eyes and quick gestures. I was scared

again, like the first time I went there.

“I’m Wild Bill,” and he stuck out his hand.

We talked a while and I told him about my photography project. He looked

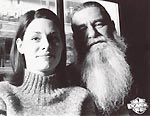

baffled that I would be taking pictures there. As evidence, I point to

the bulletin board above his head where a print hangs of Peg kissing Coxy

while her sister holds a knife to his chest length white beard.

“Why here?”

“Don’t know, interesting place I guess.”

I wanted to tell him, but how could I find the words for this wild-eyed

stranger when I could not yet articulate it to myself? The abundance of

narrative without theory or criticism, how these boxcar journey tales

and bootleg whisky memories survive with such elegance in the absence

of analyzation- how could I tell Wild Bill that his face told the story

far better than my words could ever hope for?

When I was drowning in my delusions of grandeur, when the most important

things in the world seemed to be to find the meaning of a poem or work

of literature and all the word counts, foot notes, and proper citation

that search requires, I found a place that reminded me where stories comes

from. The aspirations of greatness that flutter like leaves reaching for

the clouds were reminded that the roots are not in pages, but on tongues.

I was reminded that stories do not live between two covers; stories live

on lips.

What

are your thoughts?

Click

here to submit feedback on this story.

Return to the table of contents