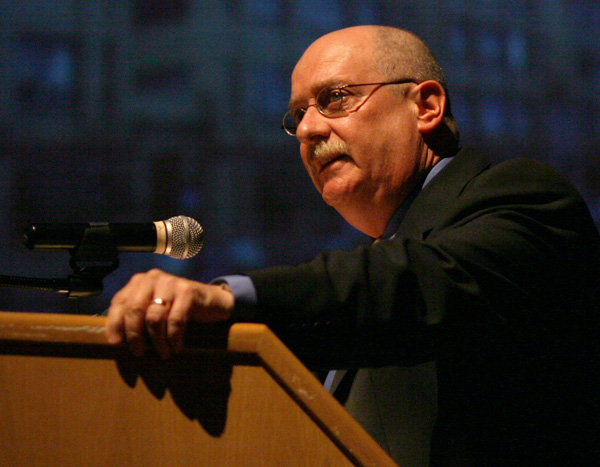

Professor Greg Huebner is the first art professor given the high honor of presenting a LaFollette Lecture. He’s also the first to step to the Salter Hall podium and declare he won’t be giving the LaFollette Lecture, after all.

Professor Greg Huebner is the first art professor given the high honor of presenting a LaFollette Lecture. He’s also the first to step to the Salter Hall podium and declare he won’t be giving the LaFollette Lecture, after all.

"I would feel more comfortable if you could suspend the thought of it being the 29th LaFollette Lecture and instead think of it as the First LaFollette Performance Art," Huebner told his faculty and staff colleagues, students, alumni and Wabash trustees as he introduced the aptly named "Life at a Half Bubble Off Plumb: Rethinking Truth, Beauty, and Jumbo Shrimp."

(See a photo album here.)

Following a light-hearted introduction by last year’s LaFollette lecturer, mathematics professor J.D.Phillips, Huebner began his artful performance with words projected over the Salter Hall stage.

"Any work of art is the sum of an artist’s life experiences, ability, and craft up to the point of the work’s creation. Therefore, whenever a student asks me how long it took me to complete a particular painting, I always respond, ‘my entire life.’"

And for the next 50 minutes, dozens of slides, and references to numerous disciplines in the liberal arts, Huebner talked the audience through the creation of his most recent painting, interspersed with autobiographical sketches of how he became the artist he is today and what inspires that work.

"The artist has absolutely no choice in the matter. You create and you make art. It is who you are and what you must do," Huebner said. "And it begins at a very early age. Growing up I was constantly making things and looking for new materials to create things."

He recalled his machinist neighbor whose "garage was like a wonderland for a boy like me. Dave Hohaus was like a second father to me, and we spent hundreds of hours working on his projects and my own."

His interests veered from tinkering to art in grade school, when in exchange for being allowed to bring a TV into the classroom to watch his beloved Chicago White Sox in the World Series, he volunteered to "do the art" on his teacher Sister Ramona's bulletin boards for the rest of his fifth grade year. He enjoyed it—both the process and the praise he received. Even after his drawing for the Easter Week bulletin board of Christ driving a 1957 Chevy convertible to heaven was rejected by Sister Ramona, he noticed that she seemed to be fighting back a smile.

Huebner took classes at the Art Institute of Chicago—his first formal art training—the summer of his sophomore year in high school.

"For the first time I had actual artists teaching me and I was surrounded by other students who were seriously interested in art. It was a wonderful experience."

At 16, he began to consider art as a vocation. But even so, he chose to attend a liberal arts college.

"I have always felt that a liberal arts education was the perfect environment for educating artists," Huebner said. "Art springs from a keen observation of the world around us, and the humanities present unlimited sources to help the artist understand what he or she is observing.

"Art comes from deep within our mind and soul, from the meeting place of the reasoned, the felt, and the observed, where knowledge becomes true understanding," Huebner said.

At first his painting was more realistic, but when he was 20 year old he encountered the paintings of Kazimir Malevich, a pioneer of geometric abstract art.

"From my first contact with Malevich I moved steadily toward non-objective abstraction," Huebner explained.

"Through non-objective abstraction I was able to find my own voice. To quote [art critic] Mel Gooding, "It was what could not be seen that mattered."

That search for the unseen has driven a career of almost four decades and more than 500 paintings.

That search for the unseen has driven a career of almost four decades and more than 500 paintings.

"Abstract painting is about love, birth, death, and all the great ecstatic experiences of being human," Huebner said. "It is like those first wild marks we make as a child, which announces to the world, "I am here! You don’t have to paint a figure to express human feelings. When I paint I am organizing moments of feelings and these moments of feelings become issues of color, light, shape, airiness, weight, lyricism, or even violence."

And as an artist in pursuit of the unseen, Huebner likes these words by abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning: "What you do when you paint is, you take a brush full of paint, you get paint on the picture, and you have faith."

"Since 1990 I have viewed my own painting as a visualization of my spiritual self," Huebner said.

That "self"—the twelve-foot-tall painting whose creation he’d documented in his lecture—was perched in the Little Lobby after the lecture. Huebner’s audience—professors of the sciences, social sciences, and the humanities—milled around it, experiencing a visual echo of the first LaFollette Lecture to be delivered by an art professor. The final product of the First Annual LaFollette Performance Art.