The first time I was tear gassed, I ran like everyone else. The piercing burn in my eyes fueled my fear, which fueled my legs to run in the only direction that existed in the moment: away. More than a thousand gathered in downtown Indianapolis protesting for the end of police brutality and systematic racism but were scattered within a matter of seconds. The “Black Lives Matter” chants turned to cries of panic.

The first time I was tear gassed, I ran like everyone else. The piercing burn in my eyes fueled my fear, which fueled my legs to run in the only direction that existed in the moment: away. More than a thousand gathered in downtown Indianapolis protesting for the end of police brutality and systematic racism but were scattered within a matter of seconds. The “Black Lives Matter” chants turned to cries of panic.

In the chaos of the running bodies was a child who had been separated from her family. She appeared to also have been tear-gassed, her eyes rimmed in red and tears streaming down her face. I helped her but I couldn’t help her. Despite all of my experience as a medical student, I wasn’t prepared for this moment in the way I wanted to be; I lacked the supplies and training but also the mindset. I felt the weight of my responsibility. I stood by her, feeling helpless until the crowd calmed down and her parents were able to spot her.

The tear gas faded, but the feeling of desperation and helplessness stayed with me. I never wanted another individual to be in the same position as that young girl again. This drove me to find a means to help in the future. I imagine it’s the same desperation that drives millions across the country to take to the streets to protest and plead for justice.

I joined a collective known as the Street Medics, a group dating back to the civil rights era, composed of volunteers with varying medical backgrounds, from novices and students, to nurses and doctors. Street medics receive training to address problems commonly found during protests—everything ranging from cuts and falls, to heatstroke, to more violent injuries from tear gas and rubber bullets.

The rules are simple: Help, but operate within your skill level. Do no harm. What draws medical students and doctors to serve is nothing different than fulfilling the Hippocratic oath we all swore to. Preserving life and alleviating suffering is not a political stance but a human one.

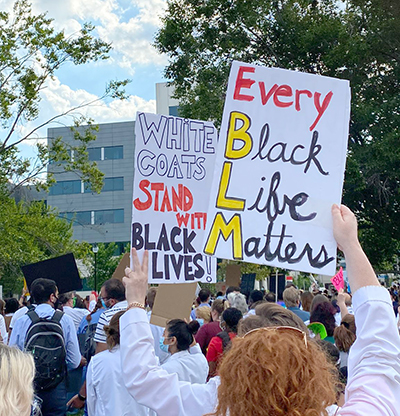

Systemic police violence against people of color has become a public health issue. After a long history of medical mistrust among the Black community, I believe now is a time more than ever for medical professionals to be visible and vocal for systemic change. In many ways, we, medical professionals, are the system. We all have to be better. For medical students, matters were certainly complicated with COVID-19 social distancing orders in place at the same time mass protests popped up across the country. Health professionals supporting this movement should not downplay the seriousness of COVID- 19, but instead should emphasize the importance of addressing systemic inequalities.

Seeing people of color cheering, clapping, and smiling as a sea of white coats marched gave me a sense of comfort knowing they felt supported, even for just a moment. My experience as a street medic was no different. My functional role of keeping individuals safe at protests evolved to a more symbolic one as the weeks passed. The instances where I provided first aid and hand sanitizer or passed out water bottles were outnumbered ten to one by other instances where I was thanked or acknowledged for being there.

I attended more as a symbol that the medical community cared, and in return, the organizers cared for us. In moments where law enforcement surrounded protesters, the voice over the megaphone boomed, “Allies to the edge, medics to the center,” directing medics to position themselves in the center of the crowd for protection. We were there to protect the protesters but in these moments they protected us. Our roles had been reversed.

As a non-Black individual, I will never fully understand what it is to be Black in America right now. I will never fully understand how many of our brothers at the MXI feel getting pulled over or walking down the street. But in this moment of role reversal, standing there surrounded by dozens who were willing to place their bodies between danger and us, I understood how solidarity felt. We all have a responsibility to return this in whatever capacity we can afford, whether it be as medical professionals, as Wabash men, or just as fellow living, breathing humans.