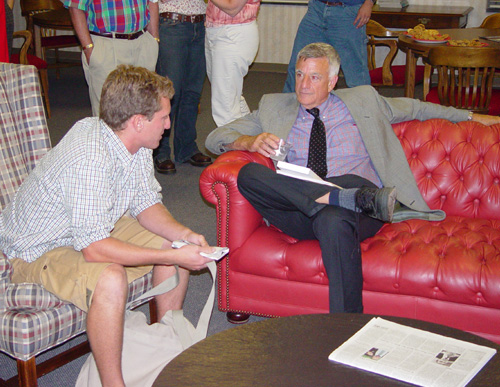

Wolfe discusses the transformation of American religion with Wabash students. |

Introduced by former graduate school classmate and Wabash political science professor Phil Mikesell ’63, Wolfe said that when asked what attracts them to their religious faith, many say they are drawn by tradition and age-old rituals “that have never changed—a rock we can attach ourselves to in such a changing, dynamic society.”

“But there is a way in which our religious traditions in America are modern and ever-changing,” Wolfe said, referring specifically to the more conservative Christian denominations.

“While Judaism is tradition, in Christianity, authentic belief in God is central, and if tradition runs up against belief, tradition loses. The very notion of being “born again” rejects tradition for the authenticity of faith.”

“If we look at religion as tradition and doctrine, we miss a great deal of how it is actually practiced,” Wolfe said. He was most surprised by the time he spent in churches in the fastest growing sector religious practice—the Pentecostal movement—including mega-churches and Vineyard and Calvary Chapel congregations with up to 5,000 worshippers.

“I was struck by the innovative nature of religion in America,” Wolfe said of the Christian rock music, video and Powerpoint displays, and weekly small group gatherings to nurture intimacy within these larger congregations. “When your mission is to get as many people into church as possible, you have to match the dynamic nature of the culture around us.”

“Individualism and personalism have re-shaped American Christianity,” Wolfe said. “Even in Catholicism, being a passive recipient is no longer acceptable. Young Catholics want a personal relationship with God. They ask, ‘Why would I need a priest, when God is already here with me, when He already understands me?”

But the most crucial way religion has changed, Wolfe said, is that the growing evangelical movement takes seriously the commission to bring others to Christ, but lacks the confidence to approach others and proselytize in the way earlier evangelists did. So we’ve seen the growth of “lifestyle evangelism,” where believers say: “If I live the best life I can, others will see the glow and follow.”

An offshoot of this approach is “servant evangelism”, outreach projects that benefit an area or group in the hope that non-believers will be introduced to Christ through the good works of His church. In this approach, non-believers are surrounded with the ambience of salvation, without being directly confronted them with Scriptures and the traditional invitation.

Wolfe quoted the pastor of one such church: “If you’re going to reach people with servant evangelism, you’ve got to make people feel good, be positive and upbeat.”

“I think he’s on to something—witnessing has to adapt to the culture,” Wolfe said. “I think we ought to admire forms of religion that want to appeal to real people in their real lives and in real times, as opposed to holding to an image of what we think religion is supposed to do for us.

“Take this sermon from one of the most conservative churches you’ll find in the United States: ‘Sex is a beautiful thing. You should anticipate it. You should enjoy it. It is not evil. At the risk of sounding crass: men are microwaves, women are crock-pots. It takes just seven seconds for a man to become aroused. But for a woman, foreplay begins when you wake up in the morning. It takes all day for a woman.’

“Contrast this view with that of Augustine, or with the image we might have of Pentecostals in the 1920s denouncing dancing and kissing bees, and this is indeed a transformation.”

People who write about religion seem oblivious to these recent adaptations and the dynamic nature of American religious practice, Wolfe said. And that includes both those who support the practice of religion as well as its secular critics. Both sides tend to draw from the same misperceptions, Wolfe said, framing believers as aliens within their own culture.

“These are not “saints” separating themselves from society,” Wolfe said—a statement some believers might find “damning with faint praise.” “Most believers are not dogmatic, not divisive or sectarian.”

“There’s no shortage of feeling alienated from society in America. If you talk to secular critics, they tell you that America is the most religious society in the world and that they, as unreligious, are the untolerated minority. Talk to religious people and they’ll tell you that America is the most secular society in the world. So there’s no monopoly on persecution.”

Wolfe said the American Civil Liberties Union “had gone too far separating Church and State.”

“If we see people as they’re actually practicing, we can tone down some of the polarized debates,” Wolfe concluded. “We can tone down divisive rhetoric and focus on the issues that truly challenge us today.”