As the bus turns left onto Cupar Way, the usually exuberant group of pastors grows silent.

Bright colors, bold shapes, and calls for unity, love, and kindness cover the expanse of view out the right-side windows. But so does the concrete wall behind the color that is topped with several feet of fencing and barbed wire that stretches as far as the eye can see.

The bus slows to a stop. We exit and cross the street. It is one of the most popular destinations in Belfast but there are surprisingly few other vehicles. There are even fewer words spoken between us as we step up onto the sidewalk.

We have 10 minutes to walk a couple hundred yards to where the bus moved down the road—10 minutes to comprehend the generations of division, hate, spilled blood, and thousands of lives lost that led to the construction of these walls.

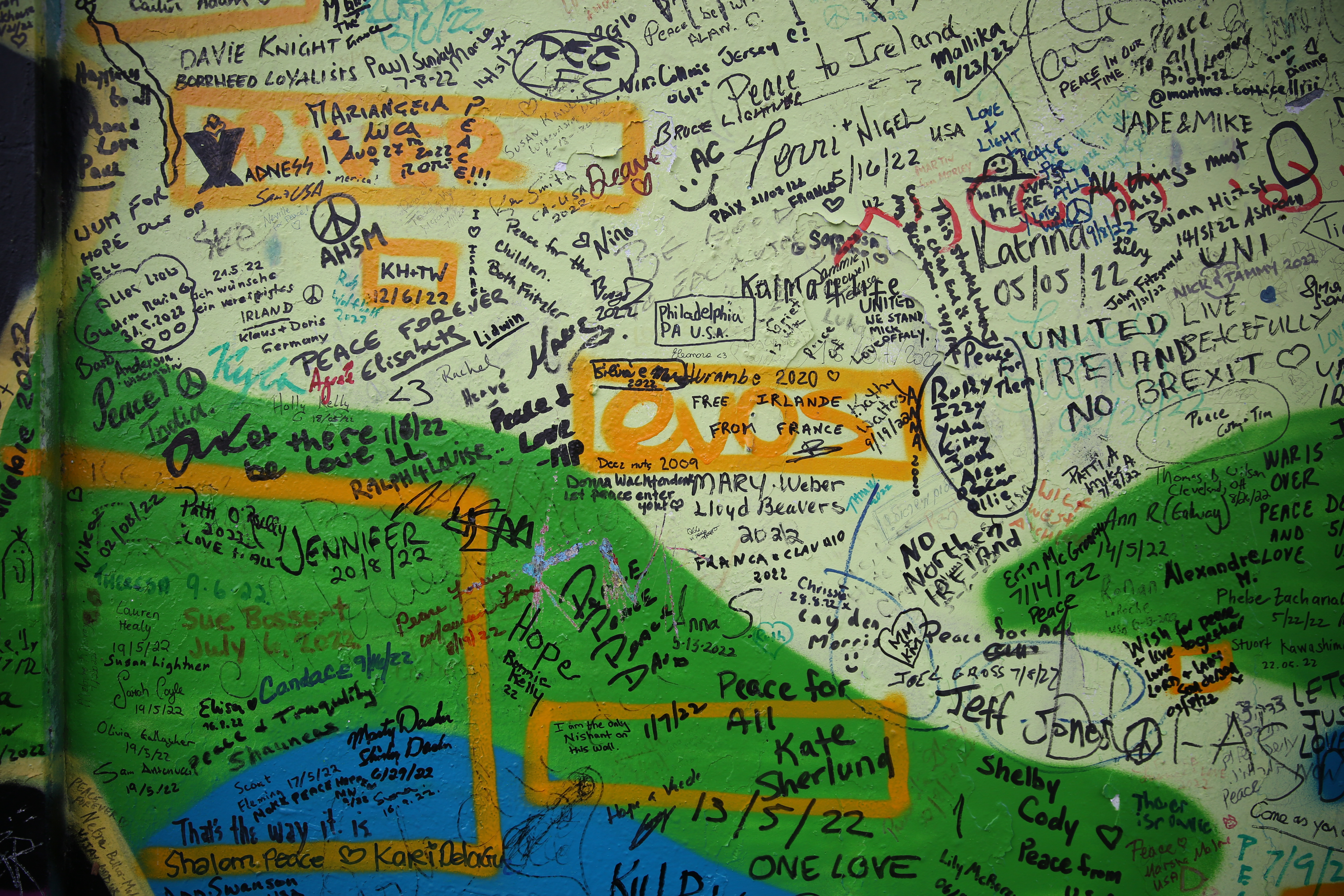

Messages scribbled in Sharpie by people from around the globe sound hopeful but are simplistic for such a complex and deeply rooted history. “Love each other; we aren’t as different as you might think.” “Through peace anything can be done.” “Peace cannot be stopped by force; it can be achieved by understanding.”

The Peace Wall on Cupar Way is one of several built in Northern Ireland in the 1970s as an attempt to separate the Catholic republicans and nationalists who desired a united Ireland from the Protestant loyalist and unionists who wished to continue allegiance with Britain.

In 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was signed, bringing an end to the most overt violence and discrimination. But since that time the number and length of peace walls built has doubled. And to this day, the streets have iron gates that close every night so no person or vehicle can pass to or from Falls Road and Shankill Road in Belfast. The blocks between the two roads saw some of the worst violence of “The Troubles.”

With the signing of the Agreement nearing its 25th anniversary, some in Northern Ireland believe it is time for the walls to come down. However, that is not the sentiment of the overwhelming majority. There are still many on both sides who believe the walls must remain in place. One never knows what “they” would do to “us” given the opportunity.

THE TEN DAY STUDY TOUR and the culmination of two years of learning together, placed the 14 early-career pastors in the latest cohort of the Wabash Pastoral Leadership Program (WPLP) in the middle of the island’s struggle to heal and move forward.

“Sometimes by going out of our own context, we’re able to have eyes to see more clearly what is actually happening in our very own context,” says Libby Davis Manning, director of WPLP.

“We visited cities with such deep divisions. The city of Belfast, for example, is deeply divided between Catholics and Protestants, between Irish and English,” Davis Manning continues. “We can begin to have eyes to imagine what is the long-term ripple effect of the divisions in our own communities now, if they are not tended to.”

The Random House American Dictionary: Pocket Edition defines peace as “freedom from war, trouble, or disturbance.” That’s Belfast now—no war, no trouble, no disturbance—just walls. The American Heritage Dictionary: Second Edition goes a little further in its definition and adds “harmonious relations; public security order; inner contentment; serenity.”

Peace on either side of the stone walls is defined differently by each person, family, and community that has been affected. The personal stories the pastors encountered through stops in Dublin, Belfast, Ballycastle, and southwest Ireland reflect generations trying to emerge into a time of “after.”

The parking lot and adjacent blocks just outside the doors of the Museum of Free Derry is where Michael Kelly and 13 others lost their lives on January 30, 1972, when a peaceful protest was disrupted. That day came to be known as Bloody Sunday.

Huddled around a small group of tables with the pastors, John recalls with gruesome detail the day of his brother’s death. The two of them, teenagers at the time, left home against their mother’s wishes. The boys were separated until John’s friends dragged him to the scene of Michael’s dying body. Michael’s blood spilled out on his own hands as John held him during the last moments of his brother’s life.

He says he no longer carries anger. He has made it his life’s work to seek justice for his brother’s death. Even prosecution and imprisonment of the solider who took his life, John admits the outcome would not change, and perhaps he will never feel as though his justice can ever truly be achieved.

We were introduced to Eugene who lost three brothers when his home was stormed and littered with bullets, literally splitting one brother in half.

A then-young British solider, John, told of being on his way to meet friends at a pub when it was bombed just before he and his girlfriend arrived. The explosion caused the building to collapse killing three of his commrads.

Beryl’s husband was murdered as he walked out the door to his car to go to work. Beryl recalls that that night in her bedtime prayer, her three-year-old daughter Gail said, “There were two bad men that came with guns and killed my daddy. Can you please make them into good men?”

Alan’s wife and father-in-law were killed when an explosion descimated the family’s butcher shop along with several other businesses on the street. He shared, “If I forgave them, my mother-in-law would never forgive me and I don’t want to damage that relationship. It’s not worth it for me.”

Each person the group encountered came from different backgrounds but their stories were all the same—violent and tragic deaths of loved ones.

With this in mind, the pastors spent a few days north of Belfast just outside of Ballycastle at Corrymeela. The residential retreat center is focused on peace and reconciliation. It intentionally creates opportunity to bring disparate groups of people around the table for conversation—including many groups and individuals throughout the height of The Troubles. Its ideology, “Together is better,” believes while our histories and identities may be different, it’s the sharing of our stories that can help bring down walls.

Irish for “lumpy crossing place,” Corrymeela sits on a lush green cliffside overlooking the coast—the beautiful landscape and hospitality of the place in direct contrast to the difficult exchanges that often take place there.

Ray Davey established Corrymeela in 1965 after he witnessed the bombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war in World War II. He grappled with the senselessness and destruction of conflict. His work, even as a prisoner of war, centered on building community and belonging for all people regardless of religious beliefs, political affiliation, background, or identity.

Alex Wimberly ’99 serves as the current leader of the Corrymeela community. The religion major recalls a line from Religion Professor Bill Placher ’70: “The best way to show our love to the whole world is to love with a peculiar passion some little part of it.”

The line serves as an anchor Wimberly holds on to even 3,700 miles away from campus. Corrymeela and the 11,000 people it hosts annually make up the little part of the world he is currently loving “with a peculiar passion.”

“It is a place where we are honestly trying to learn from one another. Trying to work through our differences and our conflicts,” Wimberly says. “That’s when we’re doing well. It requires a lot of honesty about how incomplete we are

without other people. And anytime we project ourselves as having the answer, or being the hero in the story, we’ve really lost our way. We know the next encounter with the next person is an opportunity to learn more about the world, about God, and ourselves. It gives us a more complete picture of our interdependence with each other.”

Every morning at Corrymeela begins with 20 minutes of silence. It’s a time of reading, prayer, meditation, reflection, or writing.

“Silence is such an equalizer. We can all enter into silence,” Wimberly says. “For some of us silence can be very disturbing. For others of us it is really important to have time where we’re listening rather than trying to do or be—where you’re simply receiving the moment as it comes. And silence lets us stop, pause, and allows us to tend whatever is resting with us or not resting with us.”

Like peace, silence is not always as simple as it seems. Silence can be loud or it can allow us to hear more clearly. Sometimes silence is used as a weapon, or it can be lovely and restful. Silence can be a defense, an offense, or signal complicity—either on purpose or inadvertently.

“Toxic silence is that oppressive pressure to conform to a certain way of being or to look away or disengage,” says Wimberly. “The toxic silences of Northern Ireland have allowed things to carry on in the church’s name, in God’s name, in the community’s name. That has done a great deal of damage. Too many remain silent and complicit.”

Fear of saying the wrong thing or of introducing more conflict often leads to silence—saying nothing at all.

“The work of WPLP is to help our pastors understand critical adaptive issues in their local communities so they can theologically reflect, diagnosis, then act—saying and doing the next right thing,” says Davis Manning. “We’re looking at conflict transformation, reconciliation, or relationship accountability, so that over time, we might lead more thoughtfully in the divisions that effect our local Indiana communities. We ground our WPLP program in Heifetz’ Adaptive Leadership theory, and we learn that there is no obvious technical answer to the adaptive challenges facing us. It’s hard to know what the right thing to do or say is in the midst of this acceleration of change and pain and chaos that we’re in, but say something. Don’t say nothing.

“As we’ve seen in the Ireland and Northern Ireland context, once violence is introduced to a place, it’s a tool that is used over and over again,” she continues. “The study tour, I pray, equips early-career clergy to encounter silence, be agents of reconciliation, agents of hearing each other’s story, agents of setting space for understanding across differences such that violence isn’t an outcome for the deep divisions in our Indiana communities.

“Sometimes it takes us leaving, in order to see again.”

The Wabash Pastoral Leadership Program began in 2007 and is funded by Lilly Endowment Inc. Since then, 105 pastors who serve congregations in 32 Indiana counties and represent 18 denominations have participated in the Wabash program. Directors of the program have included Raymond Williams H’66, Derek Nelson ’99, and currently, Libby Davis Manning.

During their two years as participants, the cohorts study themes relevant to their communities throughout the state by engaging in conversations with influential leaders, including small-business owners, school superintendents, social service directors, judicial officers and hospital administrators, in order to understand the complexity of the challenges facing Indiana communities. Topics have included community well-being, demography and race, the economy, education, hunger and poverty, the justice system, healthcare, conflict resolution and the environment.

“Early career pastors are great gifts and resources to the entire community. Pastors have a particular way of seeing, of being, and have a deep skill sets in relating,” says Libby Davis Manning, director of the WPLP. “We hope that early career clergy, together in conversation with local civic leaders, can engage in rich conversation around the adaptive challenges that are present in that community. And by having these different people—all of whom care deeply about the wellbeing of that place, can begin to pose and offer new responses to the adaptive challenges that are before us. Not one sector can solve the adaptive challenges by itself. But together thoughtful pastors and wise local leaders can engage these pressing adaptive challenges and find new life-giving adaptive solutions.”

At the conclusion of year one, the group participates in a study tour within the United States. And at the end of year two, they take an international study tour. Cohort Seven studied immigration with travel to San Antonio and McAllen, Texas and peace and reconciliation in Ireland and Northern Ireland.

“We host study tours, for early-career clergy to invite their creativity and their imagination to set it on fire, to set it ablaze,“ says Davis Manning. “So that we can return to our Indiana communities full of hope and possibility, filled with new questions to ask, new respect, or renewed respect for the leadership that exists so that all of us can care well for the places in which we live and serve and work.”

Reflections from Cohort Seven on the most recent study tour:

“We say, ‘I’m afraid they are going to become a threat to us or our power.’ We react in fear. The church, in particular, has the language to speak to our unifying identity—that in Christ we are more than a particular identity that we come from. It gives us the language to see the image of God and the ‘other.’ If we can see the other as having more in common with us, then we are less afraid or less likely to react in ways that fear brings out in us.”- Thomas Horrocks, Beechwood Christian Church, French Lick

“I keep coming back to the the story of the children singing outside the room as the peace talks broke down. That’s the perfect analogy for what the church should be. It should be the voices singing as things break down and reminding us to come back to the table over and over and over again.”- Michelle Walker, St. Paul's Episcopal Church, LaPorte

“We went to a pub in Ireland one night. We asked three gentleman sitting at the bar how they experienced The Troubles through the 60s and 70s. The answer was, “We didn’t at all. It meant nothing to us because we stayed away from it.” That’s how a lot of individualistic people approach life. ‘I don't even have diversity in my neighborhood. Why do I need to learn more about this?’ It reinforces the necessity to create connections between your community and communities that have more proximity to these issues.”- Jorden Meyers, Director of Ministry Services, President’s Office at the Evangelical Covenant Church

“We’re conflicted about conflict. One of the things Ireland showed me is how important it is to address conflict before it spirals out of hand in the community. Community by its nature has conflict. One of the things I struggle with, especially because of the Northern Irish context is the role of clergy in that conflict. There was a lack of voice from the clergy in a positive way. There were some pretty strong examples of negative voices in that situation. I struggle with that balance between allowing the community that I serve to work out conflict, and also where I say, as a member of the clergy, and the spiritual leader of the congregation, this is a justice issue. And this is unjust.”- Quincy Worthington, Westminster Presbyterian Church, Munster

“One of the concepts I came away with the idea that we're better together. Congregations exist because we believe we're better together—that our faith is not just me and Jesus. That extends out into the ways we are present in our communities.”- Ryan Bailey, Resurrection Lutheran Church, Indianapolis

“I stepped into a living postcard in Ireland. I was struck by the obscene beauty of it all. But underneath, there’s a current of conflict and strife. It’s easy enough for us to pretend that everything’s alright in our own personal lives, our families, or the congregation. We can think everything looks great. Like Ireland, everything was great, but underneath, there's so much more. How do we pull at the strings of that conflict to bring it out?”- Kara Bussabarger, Director of Volunteers, Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep

“One person wrote on the wall in Belfast, ‘Look after each other.’ How do we look after one another? How do we broaden the understanding of who is the ‘each other’ we’re talking about? We put up our artificial walls around the people we like. But that’s not how God sees the world.”- Erik Allen, Messiah Lutheran Church, Brownsburg

“Peace doesn't necessarily mean a lack of conflict. Peace means a deep and abiding care for the well being of a place, of a people—the interconnection of the people in a place. It is something faith leaders seek and tend to in their work of stewarding God's hope fort he world. It is not a straightforward simple reality. It is instead a long, slow, disciplined, methodical, messy journey of paying attention, listening, and adaptively leading, which we know we won’t fully live into on this side of the kingdom. And yet, the work is still to aspire towards it.”- Libby Davis Manning, WPLP Director