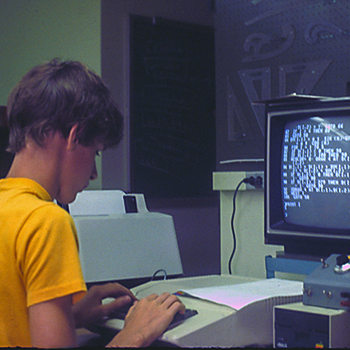

In the early 1980s, at the dawn of the microcomputing age, Chris Zimmerman, son of Emeritus Professor of Chemistry John Zimmerman, could usually be found in the Wabash computer lab on the College’s Apple II. He was a teenager at the time, but like the college students around him, he was largely learning how to program on his own.

“I grew up on campus,” Zimmerman says. “Dad was there all the time, so it was a comfortable place for me to be. I felt at home there.”

“I grew up on campus,” Zimmerman says. “Dad was there all the time, so it was a comfortable place for me to be. I felt at home there.”

As his interest and skills developed, he progressed from simple programming to assembly language, and he teamed up with his father to produce educational software to help chemistry students understand ideal gas law and chromatography.

“These were pedagogical aids for Chem 1,” Zimmerman explains. “It was an animation of gases moving around. You could play with factors like volume and temperature and see how those play together.”

Zimmerman went on to Princeton University, earning a degree in computer science in 1988. He worked at Microsoft for nine years before he and his business partner, Brian Fleming, founded Sucker Punch Productions in 1997.

They used their technical expertise to carve a niche in a very competitive field. Like so many others, they largely learned to program by making games, but they had limited experience in the space. They knew how to engineer big, technical projects.

“A lot of the companies making games had grown out of a garage culture,” says Zimmerman. “We felt like our experience could be useful. We started up a game company and hired people who had experience in games to do modeling, animation, and textures.”

Video games have an average play time of somewhere between 30 and 50 hours. That’s a lot of content. For example, in developing Ghost of Tsushima, 150 people worked on the game for six years.

“We have to create all of it,” Zimmerman says. “It’s like making a movie if you were making 25 of them. It’s a lot of work to create the content that provides 50 hours of fun for the player. There is nothing in the game that doesn’t have three or four of our developers touching it.”

Beyond putting smiles on people’s faces, Zimmerman enjoys the immersive action of playing a game. It’s not passive. The player isn’t simply watching, but making things happen. From the production side, he loves the creativity that is built into the process.

“You can see something real,” says Zimmerman, who resides in Bellevue, Washington. “What we’ve been able to do with technology is super crazy. One of the things that drew me to computer science is that it’s infinitely creative. Every second of your work day, you're creating things from scratch.”

Zimmerman isn’t shy about how his time at Wabash and that being a professor’s kid were special.

“It’s not only until you get a little older that you get the perspective of ‘Oh, wait, that was a bit out of the ordinary,’” he says. “Of course, it was special. It absolutely gave me a head start. As soon as I touched a computer, I had a connection.”

Had it not been for David Maharry’s required class in computer science, Nathan Fouts ’97 might never have carved out a 25-year career in game design. He nearly failed it.

“I just wasn’t getting it,” Fouts says. “When Dr. Maharry asked what was happening, all I could say is ‘I don’t know. I’m trying.’ He said, ‘Let’s see how the labs go.’

“I just wasn’t getting it,” Fouts says. “When Dr. Maharry asked what was happening, all I could say is ‘I don’t know. I’m trying.’ He said, ‘Let’s see how the labs go.’

“I don’t want to spoil the ending, but I pulled that grade to a C.”

Fouts aced the labs because, as he says, they finally got to actual programming. It was something he’d never done before, but he found himself really interested.

The first assignment was to write a text-based spell-checking program from scratch in Pascal. The second, a box-moving assignment, introduced him to graphics. The object was to draw the box and move it without hitting a line segment, similar to the Operation board game.

“This was very cool,” he says. “I worked on that assignment for a week. I told my roommate, ‘I think I’m making a video game.’ I went nuts with that program, constantly in the computer lab for that one tiny project. After that, I was obsessed.”

What he remembers was the sense of possibilities.

“It was the exploration of unknown worlds,” he says. “When I’m playing a game in the digital world, there are infinite possibilities in this little box with the screen. It felt almost like access to a human mind. There was competition and exploration, and that felt really good.”

Even before graduating, Fouts was building his own games and selling them via shareware. After Wabash, he spent six months in a programming job with a chemical company.

Then he got his break into the gaming business—Running With Scissors, a video game company in Tucson, Arizona. Those shareware games he designed at Wabash sealed the deal at the interview. When he showed off his work and was asked what part of it he designed, Fouts answered, “All of it.”

He later landed a gig with Insomniac Games, the company responsible for Spider-Man for PlayStation 4 and 5. Fouts worked on a number of noteworthy games, including Resistance: Fall of Man for Sony and PS3, and developed expertise in gameplay mechanics and player controls.

“I specialize in action games,” he says. “I make specifically unique experiences.”

In the mid-2000s, Fouts decided to go on his own, and founded Mommy’s Best Games. Don’t be fooled by the name; he designs a very specific type of game: classically driven first-player shooter games.

Fouts designs the games and handles all of the art—sketches, animations, scale, and colors. The business side is his responsibility, too. He manages cash flow, while identifying industry trends and receptive publishers.

“It’s gratifying, for sure,” he says. “Honestly, it’s just fantastic. Think how much easier it is to acknowledge that games are worthwhile than it was 30 years ago.”

Fouts’ next game, one he has been developing for four years, will be released in June.

The idea that Adam Phipps ’11 would ever attempt to design games was not on his road map, but in 2021, while in the throes of caring for his newborn son, he woke in the middle of the night remembering a dream in which he and his brothers were playing a game with alchemists, potions, and tokens. As he wiped the sleep from his eyes, he realized that wasn’t a game he had ever played before.

“It was a cool idea,” Adam says. “I stumbled to my computer. I knew I needed to write it all down or I’d forget it.”

When he woke up the next morning, 80% of the structure of the game—Alchemist’s Gambit—was there. He just needed to refine it—to take the time to figure out how the game was going to work.

That’s how Peach Goose Games came to life, the game-building partnership of Phipps and his wife, Julia. Both work full-time Wabash. He is the website editor and broadcast engineer. She is academic administrative coordinator to the Fine Arts Center.

That’s how Peach Goose Games came to life, the game-building partnership of Phipps and his wife, Julia. Both work full-time Wabash. He is the website editor and broadcast engineer. She is academic administrative coordinator to the Fine Arts Center.

Long before these high school sweethearts connected, Adam and Julia had been into games. Julia’s family played a lot of board games and card games. Adam’s immersion into games was similar with his family. Then in high school, friends introduced him to Settlers of Catan, the multiperson board game that inspires players to trade, build, and settle.

“It became one of my favorite games,” Adam says. “That’s really where it kicked off for me.”

The enjoyment continues to this day for both as they work together to build and play games of their own ideas.

Adam leans into the rules and how players build something together.

“I love that when you play a game, you essentially engage in a new world,” he says. “You establish a set of rules, by which you all abide, and for whatever timeframe, these rules give you a sense of friendly competition.”

Juila appreciates the sense of community and the idea of collaboration.

“I love games because they bring people together,” she says. “You come in prepared for the moment, play the game, and then you’re done. It’s a block of sacred time to spend with your friends or family.”

The Peach Goose Games partnership is a perfect match. Julia is the tactician, playing the game for feel and theme. Adam is the strategist, analyzing the mechanics.

“I play quickly and creatively,” she says, “as opposed to Adam, who will sometimes spend three minutes on a turn making sure he’s crunched all the numbers in his head.”

That creative push and pull has led to something they enjoy doing together.

“For me, it’s a hook,” Julia says. “I will play a game multiple times because I’m interested. But the rules have to be easily digestible. It can’t take 20 minutes to explain, and then you play for 20 minutes. That’s not fun.”

“The gameplay has to have multiple paths to victory,” Adam says. “Present players with options that make them feel like they can choose path A, B, or C and have an actual shot at winning.”

The goal is to create a game that keeps players coming back. It may take hundreds of hours to get it ready to be shared with others. Aside from the craft of the game or the player experience, the baseline question becomes, “Is it fun?”

“I have three solid designs that I’ve poured a lot of time into developing,” he says. “There are also nine other ideas on the table, but none of them have excited me enough yet. As soon as we start to test, we’re going to find out, is it fun enough? Because if it is, that’s when the hard work really begins.”

The process starts with building a prototype, writing a rule book, and sharing the game with friends. If the feedback is good, there are game conventions to share ideas and play with other designers, like Protospiel and Unpub. Regular meetups with other designers can also aid development.

If things progress positively, maybe the game gets pitched at a large conference like Origins Game Fair, PAX Unplugged, or Gen Con, but not before the design is strong, the graphics are on point, and the sell-sheet eye is catching. Then the elevator pitch is sharpened in preparation for publishers.

Peach Goose Games has pitched three games to date: Alchemist’s Gambit, a cooperative, “pay-it-forward” engine builder for two to four players set in Renaissance Italy; Boil Over, a fast-paced, family-friendly card game in which prep cooks try to impress the head chef; and Festival of Favors, a worker placement game for two to five players who compete as lords and ladies hosting a festival while the king passes through the region.

“Last year, I found that Alchemist’s Gambit was about 30 minutes longer than publishers were looking for,” Adam explains. “That’s kind of a bummer, but it means that my game is ready; it’s just waiting for that right spot to rotate around.”

Julia had a similar experience with Boil Over. She pitched it to four companies last year at Gen Con. All four declined, but two told her that the game was close, that a few tweaks were needed.

“I love to percolate on an idea,” Julia says. “It’s fun to identify the problem and figure out how to solve it.”

Game designers call this process polishing. It takes time to get those final elements in line so the pitch is perfect.

“The first 90% is easy,” Adam says, “but you spend a lot of time getting that other 10% done to pitch it. For so many ideas, the other 10% isn’t completed, because I haven’t figured out how to polish it off just right.

“I have found a lot of energy to continue designing and pushing through changes to get in front of publishers,” he continues. “I know the idea I’m working on is worthwhile and it is going to be published when the time is right. It will deliver something no one has ever seen before.”