I'm about to enter my 32nd year as a professional writer. That's a lot of words through my fingertips. But of all my work, the title and the character that I'm most identified with date back to 1972 and the start of my career: First Blood and Rambo. My idea was to put a furious Vietnam veteran in conflict with a troubled small-town police chief and dramatize a stateside, microcosmic version of the escalation in the Vietnam War. Ten years later, a popular film adaptation got rid of Rambo's fury about what he had endured and gave him a triumphant-victim mentality that appealed to audiences still in shock that America, despite all its might, had lost a war.

|

|

|

David Morrell is the author of First Blood, the award-winning novel in which Rambo was created.

|

Another change involved the relationship between Rambo and the police chief. In the film, the close ages of Sylvester Stallone and Brian Dennehy made them metaphoric warring brothers. But the novel was intended to depict a war between a metaphoric father and son. The police chief was a U.S. Marine who had received a Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism in the Korean War's Choisin Reservoir retreat. A generation later, as the novel opens, his wife has left him because of his insistent desire to have a child and her refusal to bear one. Determined not to let his personal troubles interfere with his job, he confronts a suspicious-looking stranger who is the age that his son would have been if the police chief had fathered a child when he came back from Korea.

It turns out that the stranger, Rambo, entered the military to escape a father who had frequently beaten him when he was young. In effect, the police chief has encountered a version of a rebellious son while Rambo has met still another version of his pushy father. The police chief's past heroism makes him believe that he can triumph over a fellow former soldier, but Rambo's unconventional guerilla tactics defeat and humiliate him. So the chief enlists the help of Rambo's military trainer, Col. Sam Trautman, whose first name echoes the nickname of the establishment that had made Rambo feel betrayed: Uncle Sam. Thus the archetypal pattern of the novel involves a metaphoric conflict between an embittered son and his "I'm always right" father, who gets help from the son's uncle. In the end, the son kills the father, and the uncle kills the son. Freud would have enjoyed analyzing this triangle.

"Where do you get your ideas?" I'm often asked. For me, fiction writing is a form of self-psychoanalysis. My psyche prompts me to imagine metaphoric versions of actual events that wounded me in ways I was too young to understand at the time they happened.

My father, whom I never knew, was an RAF bombardier shot down over France in the Second World War. When I was three, old enough to start drawing conclusions about the world, I couldn't understand why each of my friends had a man living with him in addition to a mother. Wasn't the natural unit only a mother and a child? When I was four, my mother couldn't maintain a job and still take care of me at home, so she put me in an orphanage, supervised by nuns. Later, my mother reclaimed me and arranged for me to live on a Mennonite farm, where I had my first experience with a male authority figure.

The farmer's name was Wilfred Schantz (it suddenly occurs to me that in First Blood the police chief's first name is Wilfred). He had a deep voice. He had a beard. He was muscular from his years of working the farm. And he had a thing about the way food should be eaten, each mouthful chewed 50 times. To a four-year-old, the logic behind this was incomprehensible. Every meal became a nightmare until I learned to count to 50. On one occasion, my refusal caused Wilfred to make a bargain with me: If he could defeat me at arm wrestling, I would agree to chew each mouthful 50 times. So, in the middle of dinner, he and I got down on the floor, his wife and daughter watching while we arm wrestled. At the time, I thought I had a chance. I'm sure he briefly gave me that illusion, only to finally and inevitably triumph. To this day, I'm the slowest eater you ever met, each bite chewed endlessly. But thanks to Wilfred, I learned that meals were a time for discussion, reflection, and appreciation of the food that someone had taken the trouble to prepare. He also taught me how to steer a tractor and fork cow manure onto the back of a truck.

When my mother eventually remarried, she took me from the farm to live with her and a stepfather, who never bothered to teach me a thing in all the years I knew him. In fact, he barely talked to me. My most vivid memory of him involves his half-open fist speeding at me, clawing my mouth open. In contrast, I eventually attended an all-boys, priest-supervised high school, where every teacher was male and where numerous versions of Wilfred Schantz molded my life.

First was Father Kirwan, the French and Latin teacher. He had a cord cinched around his robe, a black wooden ball attached to the end of it. When a student got out of line, he dispassionately gripped the student's forelock, bowed the student's head, and whapped the wooden ball against the top of the student's head. These days, that sounds harsh. In our current culture, someone would notify the police. But the truth is, the punishment hurt more than it did damage, and I needed to be disciplined only once before resolving never to act up again. Far from fearing him, I respected him immensely as a man and as a teacher. My fascination with the Latin grammar he taught was my first step in becoming a writer.

Then there was Father Graf, who taught woodworking. In a crowded room filled with power tools, horsing around could be life threatening, so this priest made sure we listened. If he thought we deserved it, he made us bend over until we touched our toes. Then he dispassionately whacked his belt across our taut buttocks. One blow was enough. Most of us had tears in our eyes when we straightened. Harsh? I suppose. But no one ever got hurt in his classes because of goofy antics. He died in a white-water boating accident, trying frantically to save a fellow priest.

I'm not advocating that teachers beat their students. But I keep wondering why I have fond memories of Wilfred Schantz, Father Kirwan, and Father Graf, all of whom disciplined me, while I feel only bitterness toward my stepfather, who clawed me. What makes the difference, I think, is that the first three men didn't let emotions control their conduct. They punished in the same way they taught calmly. With strength that they wore comfortably, they communicated. They made me understand what was expected of me. And somehow (this was mysterious) they made me want to be them.

|

|

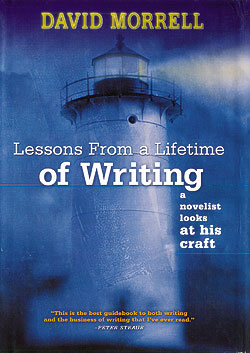

| David Morrell, author of First Blood, looks at the craft of writing in his new book. |

I eventually encountered other teachers who raised my level of ambition: Stirling Silliphant, chief writer for the legendary TV series Route 66, made me want to write stories as exciting as his were; Larry Cummings, my college literature instructor, taught me that it was normal to research and write a couple of 3,000-word essays per week; Philip Young, the great Hemingway critic, was the reason I decided to go to graduate school to become a professor; and Philip Klass, whose pen name is William Tenn, taught me just about everything I know about writing and introduced me to my agent.

None of this would have happened if I hadn't been desperate to find a father. And then, in the course of things, I became what I was searching for: a father. First to a daughter, Sarie, and five years later to a son, Matthew. Plenty to think about. The way our parents raised us programs us to treat our children in the same fashion. Sometimes, it takes awareness and will power to break the pattern. Thus, from the get-go, I was determined not to replicate the violence and indifference of my step-father. Instead, my goal was to be my own version of Wilfred Schantz, Father Kirwan, and Father Graf. To make clear what was expected in the social contract of our home. To indicate the penalty if the social contract was broken (the penalty was usually the withholding of a coveted privilege). To show respect and approval when the social contract was upheld.

Wishing someone had done it for me, I gave my son survival tips whenever I saw the opportunity, the two of us against the mysterious dangers of the world. I'm reminded of a long car trip that Matthew and I took from Iowa City to Chicago, where he'd won tickets to a Cubs game. En route, we stopped for fuel and needed to use the men's room. Standing next to each other at urinals, I directed Matthew's attention toward the flush levers. "Guys come in here all day, relieve themselves, zip up their pants, and then use one of the hands that held themselves to press that lever and flush the urinal."

Twelve years old, Matthew stared at the lever. "It's covered with germs?"

"Kind of even looks like it, don't you think?"

"No way I'm going to touch it."

"Use your elbow to press the lever," I said, referring to a lifelong habit I'd acquired on my own.

"What?"

"You're wearing a long-sleeved shirt. What difference does it make if you get some germs on the elbow?"

I fondly recall the way he grinned at me, a son thrilled that his father was looking out for him, teaching him secrets.

Three years later, Matthew was dead from a rare form of bone cancer known as Ewing's sarcoma. During his final days, unconscious, he needed to wear diapers, which I changed, reminded of when he'd been an infant. Not long afterward, my panic attacks started, and months later, when I finally managed to force myself to write again, I discovered that the focus of my fiction had shifted. Whereas I had earlier written about a metaphoric son searching for a metaphoric father, now Matthew's death led me to explore the reverse: a metaphoric father's search for a metaphoric son.

But in nearly all my books, the "son" has a desperate need to be taught, and the saving grace of the "father" is that he instructs. What my imagination is trying to dramatize, I think, is that children know intuitively it's a big scary world out there and that they subconsciously realize they need to learn ways and rules of surviving. If you're a boy, you want your father (metaphoric or actual) to be your guide, not your dominator. You want him to be strong, but to have calm strength, not only with you but with others. You want the sense that he's your teacher and, if the situation calls for it, your protector. You want to respect without being frightened. To teach and protect, the equivalent of what women call nurturing--I've come to believe that a man can't do better.

David Morrell is the author of First Blood, the award-winning novel in which Rambo was created. He holds a Ph.D. in American literature from the Pennsylvania State University and was a professor in the English department at the University of Iowa until he gave up his tenure to devote himself to a full-time writing career. His numerous best-selling thrillers include The Brotherhood of the Rose, The Fifth Profession, and Extreme Denial (set in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he lives). In his memoir, Fireflies, he discusses what his son's death taught him. His web site address is www.davidmorrell.net.