Bruce Baker '65 and the SHOUT organization give skills and the vision to live extraordinary lives to people with cerebral palsy, stroke, and other injuries that once robbed them of a voice.

It's just past 10 on a Friday night and I'm sampling the local Augustiner Amber Lager in the Station Square Sheraton's Lobby Bar. Five guys in their late 20s have pulled their chairs into a circle next to me. They're swapping stories around the blue-green glow of their LCDs, leaning back like campers around a silicon-chip fire as Pittsburgh's downtown lights glisten through the atrium glass.

|

|

|

"A reunion of hopes and dreams": Arie Hersko of Tel Aviv, Israel, enjoys an exchange of thanks and congratulation between his cousin, Ami Profeta, and Baker at the conclusion of PEC 2003.

|

Next door in the Reflections Room, their colleagues are rocking to the karaoke. A blonde teenager with tanned midriff beneath her loose, white, cotton shirt sings "Looking Through the Eyes of Love." A dark-haired young man spins from his table to the karaoke machine, taps a keypad on his wheelchair, and delivers a high-tech version of "What a Friend We Have in Jesus." Everyone joins in on Jimmy Buffett's "Margaritaville."

This could be any conference at the city's only riverfront hotel, but customers with wheelchairs and voice synthesizers of various pitches have replaced the usual bray and banter of the late night bar scene. These computer programmers, technicians, entrepreneurs, law students, musicians, and other professionals have cerebral palsy, ALS, stroke complications, or head injuries that in any other century would have robbed them of a voice and their independence.

And none of them would be here if not for Bruce Baker '65.

Baker is chairperson of the 2003 Pittsburgh Employment Conference (PEC) for augmented and alternative communicators (AAC). He's a board member of SHOUT (Support Helping Others Use Technology), the communicators' advocacy group. And he's the inventor of Minspeak--a hieroglyphic-based semantic compaction software that is more efficient than alphabet-based programs and has raised the voices of thousands around the world by giving them a fast, easily learned way to communicate.

This 10th anniversary session is a dream come true for Baker and his colleagues. Almost all of the presenters at this conference are users of AAC devices who have found their vocations. Other AAC users have come here to learn how to follow in their footsteps.

"There's no conference like this one," says speech and language therapist Colleen Haney, who led the introduction of AAC devices to Pennsylvania school kids in the 1980s and 90s before settling in Boca Raton, Florida.

At most conferences, the academics and speech "professionals" take the podium.

"But this one is for the AAC users," Haney says. "It's their chance to be in the limelight: they are treated as equals, as professionals. And they couldn't have had these hopes and dreams before Bruce and SHOUT were able to bring all this together."

Making "hopes and dreams" happen is a full time job for Baker, who also is an adjunct professor at the University of Pittsburgh, president of his Semantic Compaction, Inc., and a consultant for the Prentke Romich Company that produces the AAC devices that run his software.

But for the next three days he'll serve as moderator, tutor, and occasional troubleshooter for the 100-plus who have come from around the world to learn how to get their piece of "the American dream"--independence, a vocation, friendships, and family.

Baker exudes warmth, concern, and intensity, but as a conference MC, he's a stickler for staying on schedule. Presenters need a confidence-boosting experience; but Baker also pushes them to rise to professional standards expected in the marketplace. He knows that if AAC users are going to gain employers' respect, they'll have to walk the walk and talk the talk--even if they use wheelchairs. Most of them are up to the task.

SHOUT's new executive director, Jennifer Lowe, is an AAC user herself--a point of pride for the group. She introduces the theme of the weekend: the strategies they must learn and the partnerships they must establish to find employment.

Snoopi Botten is already well-known in these circles for his music, which he composes and sings using his AAC device. A street musician in Minneapolis, he has recorded two CDs, and he wraps up his presentation with a song.

Irene Hohn trains others to use AAC devices, and she recalls leaving the group home of one of her students and being tackled by a woman "who thought I was retarded and was trying to escape!" Her wry delivery of the tale brings howls of laughter, but such incidents are surprisingly common, as many mistake the physical impairments inflicted by cerebral palsy as mental retardation. AAC advocate Ray Peloquin urges users to educate police and other first-responders about augmented communication.

"The days of tokenism and employers hiring people with disabilities to clean toilets at McDonald's must become a thing of the past," proclaims Prentke Romich Company remote troubleshooter Anthony Arnold. "Yet while it's wonderful to dream about the job you want, don't pass up opportunities that may lead you there."

"No one is going to come to you and tell you they have a job for you," adds another presenter. "You have to go get it and prove your value. Ultimately, AAC users must be our own best advocates."

With more than half of all jobs obtained through social networking, establishing connections is more essential than ever. AAC devices give users the tool to tap into those networks.

"You can ignore someone in a wheelchair sitting right next to you," Baker says, "But when that person says, Othello,' it's pretty hard to overlook his humanity."

Moments later, a high-schooler using a wheelchair pulls up next to me. I glance at him, smile, and nervously look away. I can hear him tapping a keyboard mounted on his chair.

"Hello," the voice from the keyboard says. New AAC devices offer users a selection of voices to fit the user based on gender and age. Some offer digital sampling, and cosmologist Stephen Hawking's electro-voice even has a British accent. Chat groups have called it "sexy."

This young man's voice fits him well as he looks me in the eye and asks, "How are you?"

"Fine," I answer. There's something ridiculous about that response as it hangs in the air. He tells me his name Kyle and I notice he's wearing a speaker's badge.

"When's your presentation?" I ask.

He attempts to vocalize the answer--a technique many AAC users employ when able for short responses.

"Tomorrow?" I interpret. He nods. Through his device he tells me he's from Freeport, about 70 miles away, and he'll be going home tonight with his mom.

"Will you be coming back?"

"Of course!" he responds. Later, I'll find out that Kyle Glazier plans to become a lawyer and was a speaker at the 2000 Democratic Convention. Today he just smiles at my truly stupid question--if he's presenting tomorrow, of course he'll be back!

"Nice to talk with you," he says in his electro voice. "See you tomorrow!" He laughs and whirs off.

Driving to Bruce Baker's house from Station Square requires a sharp eye for approaching streetcars and a sheet of directions 20 lines long. Bruce provides the latter, handwritten, along with a detailed map and his phone number, to each of 40 or so guests invited to a special after hours gathering at 840 Rolling Rock, just a couple streets up from Wabash Road.

Baker and his associate, Bob Conti, have been preparing this conference for weeks, and Bruce just spent the last 12 hours hosting it--and he's got two more days to go.

But he seems reinvigorated by this party as he enthusiastically welcomes me at the door and introduces me to Barry Romich and Katya Hill, who have stepped away from the noise and grills downstairs to fix their vegetarian food. A woman reaches through the door of a kitchen and hands Baker a phone; a conferee has gotten lost trying to find the house, and the linguist will have to talk him in.

Barry Romich is president of Prentke-Romich, the assistive technology company with an exclusive license to Baker's Minspeak program and a catalog full of computer/voice synthesizers, ranging from beginner's devices like the $600 Chatbox and $2,195 Springboard to the top-of-the-line Pathfinder at $7,995.

Romich recalls the genesis of their partnership, soon after Baker had completed research for his doctoral dissertation. Setting out to study the attitudes of able-bodied people toward people with physical disabilities, Baker befriended several "subjects," finding those with cerebral palsy to be "the most interesting and insightful people" he'd met.

"Ironically, the condition which caused them to have these insights also prevented them from being able to express those insights easily," Baker wrote. His objective language masks the impact these people had on him. Their idiosyncratic attempts to reach out to the world required up to 30 minutes to complete a single sentence. Even using more advanced letterboards to spell out words was painfully slow, and hardly conducive to conversation with mainstream society.

Baker knew from his study of hieroglyphics how one symbol could contain a wealth of meanings, depending on context. Could this ancient wisdom be blended with technology to give these people a way to speak that was efficient and flexible enough to connect them with the rest of the world?

"Every time Bruce would talk with me he'd mention how a hieroglyphic-based system could help people communicate," Romich remembers. "So I was interested but I don't think I realized what a breakthrough this idea was, or how much potential was there."

Baker returns and picks up a large book with an aged leather cover.

"I need to show you my oldest acquisition related to hieroglyphics," he says. "One of history's greatest acts of linguistic sleuthery was the translation of the Rosetta Stone by Jean-Francois Champollion." He pronounces the name in a flawless French accent.

"This treasure is a first edition of his work," he says, opening the book. "And these are the original diagrams of his translations of the Rosetta Stone."

Baker's living room would make a museum curator drool. As he speaks, every object--from a museum-class trilobite and wooden parrots carved in Brazilian rainforests to a late Hudson River School painting--becomes a window into its creator. A comment I make about this "liberal arts approach to collecting" brings Wabash professor Jack Charles to his mind.

"When I think of my work in linguistics, I think of him," Baker says. "Every kid is interested in hieroglyphics, I guess, but learning how to decipher them in Jack Charles' class is what really struck the spark."

Baker's most treasured possession here is a photograph of himself with his mother, Jessie. She lived here until her death in 2002 at age 93. Twenty-one years earlier, when her son needed money to get Semantic Compaction off the ground, Jessie put up the necessary $15,000. Baker quit his job, sold his house, cashed in his retirement insurance, and plunged into developing the Minspeak concept fulltime.

"She said, 'Go for it!'" Baker recalls. "She knew that an insight like this doesn't come more than a couple of times in a lifetime."

Her basement became the fledgling company's office, and the former physician's assistant did the taxes and accounting for Semantic until she turned 82, living long enough to see her son's insight blossom into a multi-million dollar company serving thousands.

Baker has to clear his throat when he speaks of her. Gliding his hands over a first edition of James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as Young Man, he says it was Jessie who awakened him to the pleasure of collecting.

"When I was six years old, my mother bought me this," he says, cradling a children's book titled Dolly Madison's Surprise. He opens it and smiles. "She said it was a first edition, and that if this book ever became famous, this particular example would be very valuable."

My tour ends when four more friends arrive at the door.

"Guten abend," Baker says, welcoming Christian Herrmann and his mother, just arrived from Germany. He speaks with practi-cally paternal pride of Christian's progress with his Pathfinder device, pointing out that Christian is tri-lingual--French, German, and English. Christian jokes that his Pathfinder is more fluent than he is.

I leave for my hotel room recalling Baker's words: "that class with Jack Charles really struck the spark." The Wabash professor beloved for his intellectual curiosity, his fascination with different cultures, and his nurturing of community would have enjoyed warming himself by the fire his former student has made of that spark.

"Have you ever wondered what it would be like not to be able to communicate?" asks 19-year-old Sara Brothers in an American Speech, Language, Hearing Association publication. "You feel, you think, you understand the words, yet you cannot speak them. You are furious and you have to hold it in; or you are extremely happy and can't show it."

Dr. Bob Segalman, a research analyst for the State of California who spoke for the first time in public at his Bar Mitzvah more than 40 years ago, says that to imagine what it's like to communicate with impaired speech, try making airline reservations over the phone with an apple in your mouth.

But silence has more sinister implications. Musician Snoopi Botten told the University of Minnesota's Resonance magazine that his earliest childhood memory is of being sexually abused by his adopted father. Those outside the family saw a child with a room full of toys, and Botten, who has cerebral palsy, couldn't tell them that "every time my dad abused me, I got another toy. I had so many toys I hardly fit in my bedroom."

Contrast Botten's experience 20 years ago to those today of the students in the Chatterbox Club of Spokane, WashingtonÑa support group of young AAC users who meet monthly "just to have fun."

Part of that fun is singing, and Snoopi Botten is their inspiration.

"The problem is getting everyone to start singing at the same time, but we're getting better," one Chatterbox member says. Look out, SnoopiÑhere we come!"

And then there's a parent's perspective:

"When you have a child who cannot speak, you may never get the privilege of hearing the words every mom waits to hear from her child," writes Mary Bradley, whose son, David, was born with cerebral palsy and is learning to communicate using Minspeak. "But just recently, after David awoke one morning, he wanted to say something on his Vanguard device, and the words that came out were 'I love you.'"

|

|

| Randy and Brenda Kitch's first date was a Halloween dance. "And my first thought was, thank heavens, he loves to dance," says Brenda. "Randy taught me to be myself. 'Just be yourself,' he told me. 'People should see that.' |

The centerpiece of day two is a town meeting moderated by Randy Kitch, a consumer advocate for North Bay Regional Center in Napa, California, and a longtime friend of Baker's. Manipulating his AAC device with his toes, one bearing his wedding ring, Kitch has been a professional in the disability field for 28 years and is a rapid communicator with a quick wit.

"I am from California, but let me reassure you--I'm not running for governor," he says as more than 40 of his colleagues line up their chairs for the meeting.

SHOUT chairman John Bernard says these meetings have become a mainstay of the conference because everyone gets the chance to practice their speaking skills.

"We couldn't have held such a meeting when we started 10 years ago," Bernard says. "Not enough people had enough skill with the devices and the technology had to improve. Now we have folks integrated into the workforce and coming back to teach others how it's done. It's a real barometer of the progress we've made."

"The breakthrough came at the meeting where the theme was sexuality," recalls SHOUT board member David Bostick. "People had a chance to talk about something that meant a lot to them, saying things they probably had never said publicly before."

Rick and Irene Hohn have been married for eight years, and Irene says that "without an AAC device, there is no marriage."

"Communication is the key to any relationship," she writes in Sex and the Disabled: Myth or Reality. Irene leaves little doubt that "reality" is the proper answer.

"I enjoy surprising Rick," she says, and her husband concurs.

"Being married to Irene is quite an adventure. She adds spice to my life; she keeps me young."

"Rick is a wonderful man, very loving and gentle, a good provider and full of a few surprises himself," Irene says. "He is a very determined man, in spite of his handicap. And he's a doggone good kisser."

"It's not easy for two people in wheelchairs to kiss," Rick says. "But we've got it down to a science."

Wayne Roup, of York, Pennsylvania, tells of speaking to 1,300 third-grade kids. "A child asked if my brain was coming out of my head-stick, and why was I so 'wiggly,'" Roup recalls. "I am glad he asked me, because how else are people going to know the truth."

All the technology in the world won't overcome the final barrier AAC users face. Baker calls us the "temporarily-abled"--TABs for short. He says most of us, at some point, will suffer some sort of disability.

"You could have a car accident, spinal injury, or a stroke, and they send you home--no one tells you how to have sex with your own wife. You came into the hospital a person--you leave as one of 'them.'"

He practically spits out that last word, recalling a college he visited where his hostess assured him he'd have plenty of help when he met with disabled students there. "We have a woman here who has plenty of experience with them; she's very good with them," Baker recalls her saying. "It was as though people with disabilities are another species!"

|

|

|

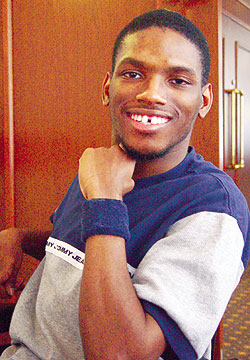

Kevin Williams: "I want to be on the cover of GQ--the GQ 'Man of the Year' who slobbers and uses an AAC device."

|

Meet Kevin Williams, a 24-year-old software developer who recently graduated from Kent State University with a degree in computer science. He's been using Minspeak-based AAC devices for nine years, and he's pretty fast. Once I get over my nervous tendency to fill with my own words the time it takes for Kevin to tap in his responses, the conversation is refreshingly relaxing--a deep-breath in a world addicted to speed. Kevin's not immune.

"Is speed an important issue to you? Do conversations feel too slow?" I ask. "Is this frustrating for you?"

"Until there is something that taps directly to the brain, it will always seem too slow to me. But this is a lot better than my old letter board."

Did having this device help you socially in college?

"People overlooked me and rushed by at first--until I showed my personality and ideas. The thinking of the whole university changed as I got out more and talked to people and they got used to my voice."

So you had to aggressively pursue conversations with people?

"Yes. You have to be aggressive because people won't come to you. They don't know what the heck this is, or how to interact, so to make them feel better you go to them. They say: 'Oh, okay, I can speak with him and not be embarrassed--he's as smart as I am.'"

That seems very generous, very patient of you.

"I have to be patient. But it's not generosity. I'm part of your society, and to be able to get what I need from you and to show you that you can depend on me, I have to speak to you."

You could just say,"to hell with these people who won't even look at me."

"How does that benefit me? I will be isolated like so many people with disabilities. I don't want to sit at home and watch TV for the rest of my life. I want to be productive.

"I want to show the world that people who use AAC are like anybody else. I want to be on the cover of GQ. That is my goal--to have a feature article in a major magazine about the style and drive of this successful multi-million-dollar computer company owner. I'm the GQ 'Man of the Year' who slobbers and uses an AAC device."

We both laugh.

"My domain name is 'llslim'--that stands for 'leaky lips slim.' If you don't take some pride in every quality you have, you won't have pride in any quality you have."

It was the most memorable moment of the 1999 Academy Awards ceremony. The film King Gimp won the Oscar for best documentary, and the film's star was so excited that he fell out of his chair. That was Dan Keplinger, a Baltimore artist born with cerebral palsy. Keplinger says that "most people think 'gimp' means someone with a lame walk. But 'gimp' also means a 'fighting spirit.'"

Advertising executive Richard Ellenson remembers when HBO broadcast King Gimp. His son, born with cerebral palsy, was two years old, and Ellenson and his wife watched the documentary in tears. Ellenson says he's honored to introduce Keplinger and the screening of King Gimp, the evening's entertainment concluding the conference's second day.

"As we watched Dan's life," Ellenson says, "we really understood for the first time that our son would not just live, but that he would live an extraordinary life."

On the conference's final day Professor Susan Balandin of Australia's University of Sydney surprises Bruce with a proclamation naming him an honorary faculty member. Baker, whose theoretical work in language representation is studied in universities worldwide, is touched by the gesture and accompanying ovation.

When PEC 2003 wraps up at noon, Baker is exhilarated and exhausted. The slight tremble in his fingers has become more pronounced as conferees and family members line up to shake his hand, and say goodbye until next time. Colleen Haney, who worked hard alongside Baker to bring AAC to many of these people, is overjoyed.

"For me, this is a reunion of hopes and dreams," she says. "Bruce and the SHOUT organization have given people the vision of living a normal life, or better. I come back to this conference and see people who were learning this technology when I was here in the schools, just catching the dream. Now they have jobs, some are married. It's so rewarding."

I meet Randy and Brenda Kitch on the way to the checkout desk and ask if I can take their picture. I mention that I'm writing a story about Bruce and his work. Randy taps his touchpad with his toes and fixes me in his gaze.

"Do him justice," he says.

It's a challenge I've not met. As moved as I was listening to these voices, as much as my own ears have been opened, I can't find the words.

But Richard Ellenson has. A father knows what this work means for his son, who is just beginning to use an AAC device.

"We live in a world searching for its center," Ellenson told the AAC users at the screening of King Gimp Saturday night. "We live in a world looking for its humanity. And everyone in this room has insight, intelligence, and depth. You need to go out of this place and deliver that to people."

Thanks to Bruce Baker and his colleagues, they will.

Read more about Minspeak at www.minspeak.com.