Look out Lutherans and Norwegian bachelor farmers--Greg Britton's take on Minnesota is reshaping the world's view of the Midwest.

| |

|

Publisher Greg Britton '84 is "at the leading edge of a demographic trend, challenging stereotypes about the Midwest," publishing books that are "resonating with readers far beyond that region."

|

So why is the Minnesota Historical Society Press (MHSP) publishing the "searing" memoir of a Korean woman? Or an anthology by young Hmong writers from a culture that didn't have a written language until 1950? Or the memoir of an elderly Ojibwa man who survived indifference and brutality in the rural state foster child system of the early 20th century?

The October 27, 2003 Publisher's Weekly says that MHSP Director and Publisher Greg Britton '84 is "at the leading edge of a demographic trend, challenging stereotypes about the Midwest," publishing books that are "resonating with readers far beyond that region."

Britton says he and his team "publish books about ordinary people in extraordinary situations."

"That's a much more interesting story to me than an extraordinary person who tells me about a life that's actually pretty mundane," Britton says. "I'm not particularly interested in publishing the memoir of a famous politician or leader. And though I love the Minnesota of Garrison Keillor, I don't want to publish that story, either. There's this whole other Minnesota that's surprising to people, stories waiting to be told."

So we get The Packinghouse Daughter by Cheri Register, who grew up in a small town about the size of Crawfordsville that was practically torn apart by a meatpacking strike in the 1950s.

We read in Baghdad Express about the misadventures and inner conflicts of Joel Turnipseed, a U.S. Marine and philosophy major in the first Gulf War whose books outsold all expectations.

Jim Heynen's The Boy's House comes closer to what readers expect from a Minnesota press. But these short tales of Heynen's rural boyhood read like parables--illuminating, sometimes disturbing, sometimes hilarious, often moving, and imbued with mystery.

| |

|

"We publish books about ordinary people in extraordinary situations. That's a much more interesting story to me than an extraordinary person who tells me about a life that's actually pretty mundane."

|

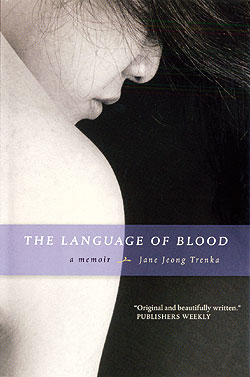

Jane Trenka's The Language of Blood uses an engaging array of genres and forms to reveal her life as a Korean girl adopted by repressed conservative Minnesota Lutherans who mean well but decide that "the best thing to do in this rural town is to never mention to Jane that she's adopted, never mention the word 'Korea,' and completely deny her birth culture."

"At a certain point," Britton says, "she looks in the mirror and realizes that she doesn't look like every blonde-haired Swede in town, and the book is about her coming to terms with that. It's also a pretty angry book--a real indictment of well-meaning Minnesota 'nice.'"

"I think that a lot of people are surprised to see that book coming from us. But I want people to pick up our books and be surprised--even shocked. I don't want to give them standard historical society fare. I want people to be surprised by our books, may be see part of themselves there and transformed by them."

Britton is quick to point out that 60 percent of the MHSP list is quite unlike these more literary titles, including popular history books such as Minnesota History Along the Highway and 75 Great Moments in Minnesota Sports. The former Wabash history major with a University of Wisconsin master's degree is no less enthusiastic about these works.

"They are popularized history--good history packaged to reach an audience that would probably rarely pick up a history book," Britton says. "Part of publishing is pulling people in--baiting the hook and reeling in the reader--and I love that part. It's what teachers do--trick or entice students into teaching themselves something. And that's part of our mission at MHS."

But The Language of Blood, Baghdad Express, and other "literary" titles on the list are gaining MHS national recognition and critical praise while earning Britton the honor of "Minnesota Publisher of the Year."

"We didn't invent 'the New Minnesota'--Minnesota has been changing`` for decades and will continue to change," Britton says. "We're just pointing it out in a way that other people aren't showing yet."

But Britton had to see it for himself first. A serendipitous first day in the state, along with skills honed during his Wabash days, brought that vision into focus.

"In 1980, I didn't just come to Wabash College--I really moved to Crawfordsville," Britton says. You won't hear that from many Wabash students or alumni.

"I got a library card, I moved off campus as soon as I could, and I walked everywhere. I was jazzed by the local history, the local lore, and really interested in how this place got here, who moved here, who lived and died here, and the meaning of it as an economic place, a political place, a cultural place."

So Britton walked the railroad tracks.

"What I learned in Crawfords-ville and at Wabash, from teachers like Peter Frederick, was how to read a streetscape, how to think about a place, to understand where the railroad tracks go. I used to walk the tracks here, and you see a city very differently if you walk along the tracks instead of just cross them."

Arriving in St. Paul more than a decade later, Britton got his view from "along the tracks" when he stepped into the downtown license branch on the first day of his new job.

"I was standing in this long line, it was a Wednesday morning. There was a Hispanic family in front of me. In front of them was a Somali man. In front of him was a Hmong woman. You had the choice of taking the driver's license exam in many different languages. As I was looking around at this ethnically diverse crowd, I thought, I may be the only Anglo person. I may be the only native-born person in the room.

I was approaching the front of the line, listening to all the different languages, when the clerk said, 'Driver's license please.'"

"I pulled out my Wisconsin driver's license, and she picked it up and smiled.

"'You're from Wisconsin. You're an immigrant. Welcome to Minnesota.'

"And I realized she was right. I'm not from here. So I feel as though I came to Minnesota as an immigrant as well, and I try to look at the place through that lens."

In a state rich with immigrants' stories--whether they are fourth-generation Norwegian farmers, second-generation Hmong urbanites, or displaced Ojibwa Indians--that epiphany was a windfall for a publisher. Britton and his creative team aggressively seek out works from these diverse groups by taking full advantage of what Britton calls "an amazing creative hothouse" of literary activity in Minneapolis- St. Paul. The metro area is home to three small nationally known literary presses, a university press, the Loft Literary Center, and a community of writers, poets, and publishers who share a common passion for the written word.

| |

|

"When I travel to small towns I see them being bleached out by this corporate monoculture of Wendy's Subway, Wal-Mart--they're all starting to look alike . . . Regional distinctions that exist now will be gone in a generation, and one thing we can do is capture them and put them in a place that's lasting."

|

Britton's MHS Press is in the thick of it and thriving, driven by his mission to tell important stories and bring history and a "sense of place" to all those he can entice to pick up his books.

"When I travel I see small towns being bleached out by this corporate monoculture of Wendy's, Subway, Wal-Mart--they're all starting to look alike. And one of those things we feel evangelical about is the importance of regional distinctions that exist now but are fast disappearing," Britton says. "They'll be gone in a generation. One thing we can do is capture them and put them in a place that's lasting."

MHSP will continue to do that by telling stories of "ordinary people in extraordinary situations," something Britton is reminded of when he goes home at night to his wife, Marlene Meyer, who works as a family therapist for the county school system.

"She was telling me about a single father who has a full-time job, and a child with health problems; he's doing everything right, but they are homeless, because he has decided to buy health insurance for his son, and the choice is home or insurance. It's heartbreaking. Increasingly, that's the sort of choices parents have to make. It reminds me that there is a different Minnesota, a different America out there. It has always been a place of many different experiences and struggles, and that's a better story, and a much more important one."