"People could die out here."

Samana, Dominican Republic (AP)—Tropical Storm Jeanne hovered near hurricane strength as it plowed through the northeastern Dominican Republic on Thursday, prompting thousands to flee their homes a day after pounding Puerto Rico and killing at least three people. More than 8,200 Dominicans were evacuated and took refuge in shelters set up in schools and churches, officials said.

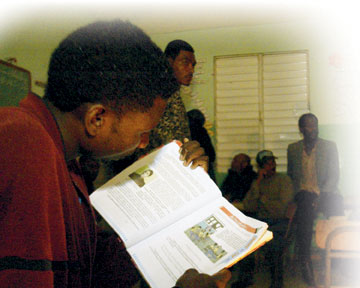

"I had to come here because at night this becomes scary," said Mario Vasquez, a 40-year-old farmer who crowded with 150 people into a school in blacked-out Samana. "People could die out here.

The fear in Miguel's eyes told me we were in trouble.

Debris and rocks flew through the air while palm trees and telephone poles were crashing onto the country road we were traversing. Gusts of horizontal rain blasted our jeep like ocean waves, reducing visibility to zero for seconds at a time. The wind seemed to come from all directions, clanking and howling as it cannon-balled into our jeep and shoved it sideways across the pavement inches at a time.

"Miguel, we've got to get out of this," I yelled to my photographer, who was driving.

Miguel flashed a look at me.

"Where the hell are we going to go?" he yelled back.

Our day had started out easy, even boring. We had spent hours driving around the northeastern peninsula of Samana in the Dominican Republic, waiting for Hurricane Jeanne to smash into the island. But it never seemed to arrive. We even thought that perhaps we had chosen the wrong location. Maybe it would hit another part of the island?

Jeanne was the third hurricane I had been assigned to cover in September in what would prove to be one of the worst Caribbean storm seasons in years. With my previous experience, I had come to the conclusion that predicting where a hurricane might hit is just about impossible. The beasts have minds of their own.

Meteorological experts use fancy satellites and send robot planes into the storm to collect data, but the best they can do is predict a hurricane's immediate route-which is always changing. This time they had predicted Jeanne would hit Samana.

Government officials in the capital of Santo Domingo had declared Samana in a state of emergency. Radio and television stations were urging people on the peninsula, known for its aqua-blue beaches and lush vegetation, to leave their houses and get to shelters. Stores closed and windows were boarded up.

Miguel and I interviewed a woman who was helping her elderly father tie down the zinc roof on their wooden hut, a typical construction in one of the country's poorest regions.

"We are all afraid of what's coming," 17-year-old Julie Acosta told me as she wound the rope though holes in the roof and tied it to a palm tree.

I asked her if she and her father would go to a shelter, knowing their hut would never survive a hurricane.

"I don't know," she said. "We have to protect our things."

"Maybe the hurricane won't hit here after all," I told her as I looked at my watch. It was 4 p.m. Miguel and I had already paid for a hotel in the town of Las Terrenas and sent our editors photos and text of people preparing for the storm. All we could do now was wait.

"Let's take a drive and see what's happening in other areas," Miguel suggested.

We decided to go to the town of Samana on the other side of the peninsula. Since it was only 25 miles, we calculated a quick trip and return before dark. We never made it back to Las Terrenas.

The rural road through the small mountains was lined by hundreds of palm trees that popped through thick tropical plants. There were hardly any cars on the road-every few minutes we saw somebody on horseback or passed men leading donkeys carrying goods.

When it began to rain about 15 minutes into the trip, we didn't worry. It had been raining on and off all day, normal in the tropics.

Then the sky went black. Within two minutes, the light rain became a raging gush and the lazy palm trees were shaking violently in the wind. A telephone pole fell about 50 yards ahead of us; Miguel swerved left to avoid the collision. The wind seemed to be getting stronger by the second. A sense of shock and sharp self-criticism pierced us: the hurricane had arrived and, thanks to our foolishness and impatience, we had no place to take refuge.

"Pull over," I yelled so Miguel could hear me over the roaring wind. "We've got to get out and find shelter before something smashes us."

"You're crazy," Miguel screamed. "We'll keep moving until we find someplace safe."

SAMANA, Dominican Republic (AP)—In Samana, a north-coast Dominican town where the storm stalled for some 10 hours overnight, people ventured out of a shelter into the calm of the storm's eye thinking it had passed, only to be attacked by hurricane-force gusts driving horizontal sheets of rain. Jeanne tore off dozens of roofs in the town of concrete homes.

It slammed a man riding a motorcycle into a telephone pole, killing him instantly . . .

Then it started raining. We hoped the precipitation might be just a small tail of the original hurricane. But soon the thundering wind and sheets of water battered us again, and the darkness left us with no peripheral vision to see the objects falling all around us.

Suddenly something smashed into our windshield, shattering the glass into spiderweb-like matrices and sending Miguel and me into a full panic. We screamed every obscenity we ever knew at each other, rolling down our windows to stick our heads out to see as we frantically pushed on into the darkness.

Even with my head outside, the wind and rain made me feel like I was trying to see something underwater in a chlorinated pool. The next flying object to strike where our windshield had been might just take off one of our heads.

"Slow down! Slow this damn thing down," Miguel yelled. "I see a light over there."

I looked out Miguel's window. About 50 yards off the road was a small beam being turned on and off. I pulled the car over and we ran toward the light. As we approached, a door with a steel screen opened.

"Hurry, get in!" a voice told us. The door closed behind us, lowering the hurricane roar a few decibels.

"I saw your headlights and thought 'What are those crazies doing out there?'" the man, about 35 years old, told us. "I decided to flicker my flashlight in case you needed help."

Miguel and I were panting and speechless. This man had saved our lives, or at least kept us from severe bodily harm. "Thank God," I managed to say. "Thank God for you and your light."

I sat down on the stone floor and put my face in my hands. If I hadn't been so jittery I might have cried right there. How could we have fallen into this situation again?

We spent all night on the floor on this man's stone garage next to his wife, his three kids, and about 12 others the man had seen in need and beckoned in with his flashing light. I thought about the women I had interviewed at our last shelter, their young children, all the people walking on the road. I wondered if they felt terrified, as I had, when the storm started anew. How many had made it through the night? Would any of the government agencies show up to do a body count or help survivors rebuild?

The storm let up around 5 a.m., but Miguel and I didn't dare move until daylight, two hours later. Over the next two days, our job would be to make sense of all that had happened to the people in Samana. The destruction had been major: thousands of homes obliterated, dozens of roads impassable, an entire season of crops ravaged and at least 25 dead according to authorities, though Miguel and I knew the real number had to be much higher. Government agencies hadn't even shown up until about 15 hours after Jeanne's passage.

The people of Samana had lived a nightmare. For me, Elizabeth Javier, a 12-year-old Miguel and I interviewed the day after Jeanne passed, summed up how hard waking up from it all would be.

When we saw her, Elizabeth appeared lost as she stood where her family's living room used to be. The storm had blown off one wall of their small wooden house and the entire roof, scattering chairs, mattresses, cooking utensils and clothes across the yard. Elizabeth said her mother had decided to walk through the streets looking for people who would help. I doubt then, as I do now, that she ever found anyone.

"I don't know what we are going to do," Elizabeth said, on the verge of tears. "I don't know what we are going to do."

Peter Prengaman is an Associated Press correspondent based in the Dominican Republic. Contact him at: pprengaman@ap.org

Photos by Miguel Gomez