Nearly 13,000 men died at the Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia during it s 15 months of operation, often at a rate of 100 men per day.

Nearly 13,000 men died at the Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia during it s 15 months of operation, often at a rate of 100 men per day.

Thomas Asbury Gossett was one of the survivors. Captured twice by Confederate armies, the great-grandfather of the late Andrew K. Houk Sr. ’37 wrote in 1885 a memoir of his imprisonment, describing in harrowing detail the horrors of the camp.

Wabash Archivist Emeritus Johanna Herring, who transcribed Gossett’s handwritten pages in 2005, finds the diary rare among the many accounts written of the Andersonville prison.

"Other Andersonville diaries were often written after the experiences and there was a tendency for authors to exaggerate the horrors they experienced so the diaries would sell better. They also tend not to describe the positive acts of Southerners toward Federal troops," Herring says. "The Gossett diary was also written after the experience, but it seems to be fairly balanced between detailed accounts of the extreme hardships he endured and the kindnesses of the ‘enemy,’ when they occurred."

Some edited excerpts:

Captured

We surrender gracefully and march toward Lee’s headquarters…over the same ground which not an hour ago we had driven these rebels.

A Georgian desperately wounded and almost ready to die lay in our path. One of our guards noticed he was his brother. Our guard’s feelings were overcome. The man who had faced danger from Fair Oaks to Gettysburg, broke down at the sight of a dying brother. Our captors moved us on, allowing the man to remain with his dying brother.

The night we remained at Lee’s headquarters was spent in social chat with our guards. Jokes were given and taken, songs were sung, trades were made, stories of the war were told etc. and all passed off pleasantly. We have often thought of the kind treatment we received at the hands of Lee’s men, compared to that which we received afterwards. Today I honor the men a great deal more highly who faced us in battle, than those who remained in the rear and robbed and killed and starved us in their prison pens.

Arriving at Andersonville

No part of our country could surpass this part of Georgia for its tall, graceful, long leaf pines. We found numerous pine knots that we used to burn during February and March; they gave out considerable heat with a very black smoke which…thoroughly covered us. We never got rid of it as long as we remained at Andersonville.

When I first entered Andersonville, only that portion of the stockade north of the stream and bog was completed. They were at work on the south end, and they drove stakes at short distances from each other and about 20 feet from the stockade. A guard was stationed whose duty was to arrest any prisoner who might cross to the space between the stockade and these stakes. The punishment was bucking and gagging, or hanging up by the thumbs.

My especial friend, David Sanders, saw a piece of pinewood which he wished to possess lying near the stockade. He crossed the forbidden ground and the guard ordered him to halt. The patrol was called. Sanders was taken near the south gate, bucked and gagged [a piece of wood tied in his mouth, another piece of wood behind his knees, then tied so that he could not move]. He was placed on the sand in a sitting posture, but the heat and pain so overcame him that he fell over on his side in which position he was left for half a day. None of us dared remonstrate for fear of meeting the same fate. Up to this time Sanders had enjoyed good health, but from this time on his health declined until death ended his suffering.

The Dead Line

The stakes I have mentioned were capped with a lathe and this formed the celebrated dead line. The guards stationed in their sentry boxes were ordered to shoot down without warning any man who passed this dead line and every guard who killed a Yankee was allowed a furlough for 30 days. Reckless shooting was no uncommon thing.

A member of my own regiment, Maurice Prindeville, was thus shot in the night when asleep and while lying at least 10 feet from the dead line. The bullet took effect in the top of the head tearing the skull to pieces. We were so thick on the ground that it was almost impossible for a bullet to enter the stockade without hitting someone. I have no doubt but some men crossed the dead line on purpose to be killed and thus put an end to their sufferings, choosing to die a quick death by the bullet rather than a slow one by starvation and disease.

Sergeant Howard

Sergeant Howard was young, intelligent, and of a very lovable disposition. His form was almost as delicate and handsome as that of a girl. He had been wounded through the thigh [in battle] and placed in one of our field hospitals. The wound was healing nicely, but the rebels captured the hospital and brought Howard to Andersonville.

He had succeeded in bringing with him some soap and a sponge which he used to dress his wound. Under his treatment and the help we could render, his wound was almost healed.

He had succeeded in bringing with him some soap and a sponge which he used to dress his wound. Under his treatment and the help we could render, his wound was almost healed.

Dr. Rowzie had been changed from our ward and a young upstart sent in his place. When that doctor saw the wound he demanded then to dress it. Howard begged him not to do so, as he was afraid of getting gangrene, but the doctor was inexorable. Howard then asked him to use his (Howard’s) sponge, saying that the doctor had been using his sponge on gangrene sores and by that means he would communicate the disease to him. The doctor replied that there was no danger and to work he went, Howard begging all the time for his life.

Gangrene set in, the flesh on Howard’s leg was eaten to the bone, and the poor fellow died, a victim either to ignorance or pure hellishness. I attributed it to the latter.

Tell it to our children

The dead wagon came to remove a body for interment. This was an army wagon and was in charge of [burying] Negroes. These dead were pitched into the wagon as cholera hogs at the north are handled, until the wagon was full, arms and legs sticking out from the promiscuous heap.

A great many corpses were so far gone by putrefaction that the flesh slipped from the bone, the stench was almost intolerable. They were then driven to the cemetery where a long trench had been prepared. One man would then be placed in the trench, then another by his side, but with his head in the opposite direction. At the head of each man is a stake with a number placed on it. In such a manner were over 13,000 of our brave boys buried at Andersonville, GA. Allowing three feet to be occupied by each dead man when laid side by side, it would take a trench over seven miles to hold the dead. Suppose in Indianapolis the people should die off in nine months to the amount of 13,000—the papers of the world would announce the terrible catastrophe in significant headlines.

Can you blame us who saw and endured this suffering for heralding to the world the terrible scenes enacted here? We want the world to know the facts; we want every loyal man and woman to know the facts; we want that vast host of people in the South, who were honest in their convictions about secession but who did not approve of such work, to know the truth about the matter. We want unborn generations to know who the responsible parties were and for what purpose done. We will tell it to our children with an injunction that they hand it down to those coming after them. God grant that such scenes and such suffering may never be witnessed again on this continent.

Read more of the Thomas Gossett Diary.

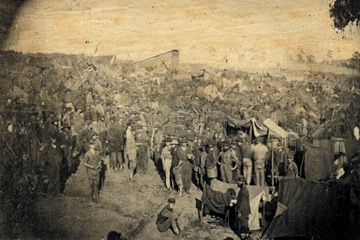

Photo: Prisoners gather for rations, Andersonville, 1864