The World Food Program brings relief to more than a half-million people terrorized by rebel forces in a conflict that has killed thousands, destroyed communities, and robbed the Acholi people of their children.

Richard was just nine years old when he was taken from his village by the Lord’s Resis-tance Army (LRA), a rebel force that has terrorized northern Uganda for the last 19 years. Brutalized into serving the LRA, the boy witnessed and committed innumerable atrocities. One of an estimated 30,000 children abducted since 1990, Richard was constantly on the move, running through the bush across northern Uganda and in and out of Sudan. Finally, during a clash with the Ugandan army, he was shot in the leg and left behind by his fellow fighters.

Richard was just nine years old when he was taken from his village by the Lord’s Resis-tance Army (LRA), a rebel force that has terrorized northern Uganda for the last 19 years. Brutalized into serving the LRA, the boy witnessed and committed innumerable atrocities. One of an estimated 30,000 children abducted since 1990, Richard was constantly on the move, running through the bush across northern Uganda and in and out of Sudan. Finally, during a clash with the Ugandan army, he was shot in the leg and left behind by his fellow fighters.

"That was the luckiest thing that ever happened to me," says Richard, now 17.

How long that luck will hold is an open question in a region still reeling from what the United Nations has termed one of the world’s "forgotten crises."

Take the road north out of Uganda’s capital, Kampala, and for about three hours you drive through some of the most fertile land in Africa. Shady banana groves give way to fields bursting with ripening corn and cassava; fresh green shoots thrust upwards through the rich, red earth, and creepers wind their way along branches and up the telegraph poles and wires to form looping canopies over the road. The villages are bustling, with eye-stinging cooking smoke drifting from busy food stalls and mounds of produce piled up on the roadside—a permanent market in full swing.

Then the road dips sharply and you are crossing the Nile, a white, foaming torrent, cascading towards Lake Albert, some 50 miles to the west.

And everything changes. It is as though you have crossed a border—and indeed you have, though it is not a frontier recognized by any authority. You have just entered the territory of operation of the Lord’s Resistance Army.

The land is no less fertile here, and if you are driving in the middle of the day, there are still plenty of people tilling the fields close to the road. But venture more than a couple of hundred yards away from the roadside and the fields give way to wilderness. Even in broad daylight, no one is going to take the risk of working out of sight from the Ugandan army patrols. The road leads through several villages, long abandoned, with trees and bushes growing in the middle of roofless structures. Some of the buildings, such as schools, remain intact, with chalk writing still on the blackboards. But they, too, are empty. By mid-afternoon, the people are off the land and back on the road for the long walk back to protected camps.

No one stays out at night.

A war of staggering brutality

Their fear is well grounded. Led by a former altar boy, Joseph Kony, the LRA has no clear political agenda, other than a determination to overthrow President Yoweri Museveni and a vaguely professed aim for society to live by the Ten Commandments. Its method of achieving this has been to wage a war of staggering brutality, officially directed against the Ugandan government, but in practice against its own people, the Acholi of northern Uganda. Villages are burned to the ground, their adult inhabitants hacked to death. Those left alive are often horribly disfigured, their lips, ears, or noses cut off by the rebels.

Their fear is well grounded. Led by a former altar boy, Joseph Kony, the LRA has no clear political agenda, other than a determination to overthrow President Yoweri Museveni and a vaguely professed aim for society to live by the Ten Commandments. Its method of achieving this has been to wage a war of staggering brutality, officially directed against the Ugandan government, but in practice against its own people, the Acholi of northern Uganda. Villages are burned to the ground, their adult inhabitants hacked to death. Those left alive are often horribly disfigured, their lips, ears, or noses cut off by the rebels.

But the greatest impact has been on the children, more than 30,000 of whom have been abducted. The boys are trained to become fighters and to carry out the same atrocities that they saw committed against their own families. The girls are forced to become "wives"— meaning sex-slaves—for the commanders.

Almost two million people from the four districts of northern Uganda—Gulu, Kitgum, Lira, and Pader— have been displaced by the conflict. They have abandoned their homes for the relative safety of congested, unsanitary camps, where they are at least protected by the army.

I first came to northern Uganda early in 2003, to Gulu district, and I was shocked and bewildered by what I saw—that so many people could have their lives totally disrupted by so few rebels. In Gulu alone, more than 460,000 people are living in camps, unable to provide themselves with a livelihood and dependent on food rations from the United Nations World Food Program (WFP).

But bad as things were, there was a tiny glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel. There was a faint hope that the LRA, worn out by years of fighting in a hopeless and senseless cause, was looking for a way out. In the months that followed, the process of negotiation got under way and a number of rebel commanders came out of the bush. There was even talk of a peace agreement being signed at the beginning of 2005.

I started to prepare for a second visit to Gulu. This time, I hoped to see and to support efforts towards post-conflict recovery. It would be a slow and complicated process, with a great deal of continuing fear, suspicion, and resentment, but at least the killings and abductions would stop.

Dusk empties the streets

Unfortunately, the forecasts were overly optimistic. When I got to Gulu for my second visit in September 2005, I found the war still going strong. Rebel activity had declined, but had not stopped altogether. The people were still living in fear.

I interviewed the rebel commander who had been negotiating the peace agreement for the LRA. He had recently defected from his comrades in the LRA in fear of his life. Even in Gulu town itself, which wears a cloak of normality in daylight hours, with shops, restaurants and businesses apparently flourishing, the onset of dusk empties the streets as people scuttle home and lock their doors. And for thousands of children, their homes near Gulu town are not considered safe enough. Their parents prefer to send them to special shelters, behind high wire fences, where they sleep head-to-toe in crowded tents or disused classrooms, safe at least from the abductors.

At first light, the children head for school, which could mean a walk of up to five miles, as nearly 90% of Gulu’s schools have been abandoned and relocated. At the end of the school day, many of the children return straight to the shelters, perhaps not seeing their parents for days on end. For these "night commuters," as they are known, family life is a thing of the past.

The only way to keep people alive

To get an idea about life outside the main towns, I drove for about an hour due north of Gulu, in the direction of the Sudanese border, to a huge camp for displaced people at a place called Pabbo. We traveled with a WFP food convoy, bringing the monthly ration for half of the camp’s 45,000 inhabitants—425 tons of corn, pulses, oil, and a highly nutritious corn-soy-blend, fortified with vitamins and minerals. Another convoy would travel to Pabbo the following day, carrying food for the other half of the camp’s population. Our convoy was escorted by 60 Ugandan soldiers in an assortment of trucks and armored vehicles. The men were armed with assault rifles; one of the trucks had been equipped with an anti-aircraft gun, which, the commander assured me, was highly effective against attack from the ground. WFP convoys like these are crossing northern Uganda six days a week, every week of the year. That’s the only way at present to keep people alive.

To get an idea about life outside the main towns, I drove for about an hour due north of Gulu, in the direction of the Sudanese border, to a huge camp for displaced people at a place called Pabbo. We traveled with a WFP food convoy, bringing the monthly ration for half of the camp’s 45,000 inhabitants—425 tons of corn, pulses, oil, and a highly nutritious corn-soy-blend, fortified with vitamins and minerals. Another convoy would travel to Pabbo the following day, carrying food for the other half of the camp’s population. Our convoy was escorted by 60 Ugandan soldiers in an assortment of trucks and armored vehicles. The men were armed with assault rifles; one of the trucks had been equipped with an anti-aircraft gun, which, the commander assured me, was highly effective against attack from the ground. WFP convoys like these are crossing northern Uganda six days a week, every week of the year. That’s the only way at present to keep people alive.

Conditions at Pabbo camp are appalling. It is a sprawling mass of grass-thatched, round mud huts, jammed together between mountains of garbage and open sewage ditches. When it rains, the ditches overflow and many of the huts are flooded with contaminated water. Cholera outbreaks are frequent. And with pools of stagnant water providing perfect mosquito breeding grounds, malaria is a major killer. Cooking is done inside the huts on open fires. As a result, it is common, particularly in the dry season, for the grass roofs to catch fire and for the flames to spread from hut to hut.

The camp has one small health clinic, with a long line of people—mainly women with small children—waiting outside. There’s not much the nurse in charge can do. The only drug in his dispensary is quinine, which can provide some relief against malaria. Other than handing out quinine, all he can do is diagnose and advise. A growing number of patients are suffering from HIV/AIDS—there is no official figure for HIV prevalence in the camps, but it is estimated to be at least twice has high as the official national figure of 7%. There is no treatment available here.

The one thing the people at Pabbo have going for them is that they are not hungry. The most vulnerable among them—nursing and pregnant mothers, small children, the elderly, and those infected or affected by HIV/AIDS—get a full food ration every month from WFP. All the others—who are assumed to have some access to cultivation or other means of livelihood—get a 50% ration. And this system applies to all across the 135 camps in northern Uganda.

No memories of normal life

Gradually, things are getting better. The government has begun a "decongestion" process: where the security situation allows it, people are being moved from huge camps like Pabbo to smaller, less crowded centers with better conditions. Most important of all, these centers are closer to the inhabitants’ own land, allowing them to work their land and produce food for themselves, rather than remain dependent on WFP.

This should allow WFP gradually to move away from general food distribution to development projects aimed at helping northern Uganda get back on its feet when this conflict finally ends. WFP has already taken significant steps in this direction through its school-feeding operations and supporting school gardens and tree nurseries.

WFP is also supporting vocational training projects for former LRA fighters to help them assimilate back in society.

And they are going to need a lot of help.

And they are going to need a lot of help.

Some were abducted at such a young age that they don’t remember their parents or even the name of the village they came from. They are also terrified of being ostracized or persecuted by their communities.

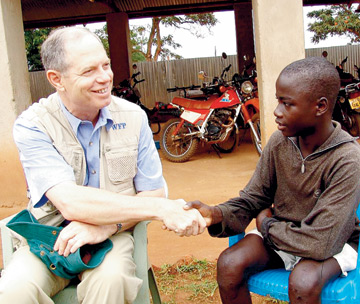

At a rehabilitation center in Gulu, I met two of these young people. Richard, whose story began this article, and Nighty, now 14. Abducted when she was 11, Nighty still found it difficult to talk about what she had been through. But her eyes told of the horror as her fingers picked constantly at the hem of her shirt.

For the children and young men and women of northern Uganda, there are no memories of normal life. They simply do not know what it is like to go to school, work, eat and sleep without constant fear.

The LRA is generally believed to be falling apart; there are thought to be only about 600 fighters left out in the bush, or so say former LRA commanders who have given themselves up. Many of these fighters are not even in Uganda, but in southern Sudan or the Democratic Republic of Congo, adding to the confusion, complication and uncertainty of the situation.

But even this small number is enough to terrorize the entire population of a region the size of Indiana. The peace agreement may be just around the corner, but recovery and reconciliation will take many more years to come.

The people of northern Uganda are going to need all the help they can get. And teenagers like Richard and Nighty—their childhoods stolen and memories haunted —deserve no less.

WFP (the United Nations World Food Program) is the world’s largest humanitarian organization, working in over 80 countries around the globe. Michael Stayton is currently chief of staff for the executive director of WFP, headquartered in Rome, Italy.

Contact him at michael.stayton@wfp.org

Photos by WFP/Janine D'Angelo