We honor the past not by repeating what these men of our history did, but when we attempt to live as they lived, to dream as they dreamed. They were pioneers; they demand that we be pioneers.

We honor the past not by repeating what these men of our history did, but when we attempt to live as they lived, to dream as they dreamed. They were pioneers; they demand that we be pioneers.

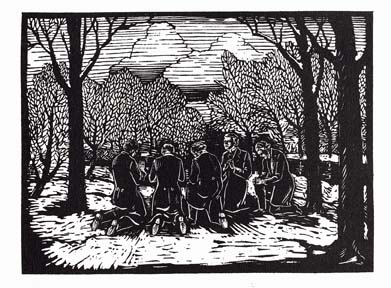

All Wabash men know the story of the founding of the College, when a small group of Presbyterian ministers knelt in the snow on November 22, 1832, to pray.

I do not think there were long prayers that day. The snow was cold, and there was work to be done.

So the founders of Wabash stepped boldly into the future. There was great need here, they felt, for a college in the Wabash Valley. In the founding document of the College they described their work: "Resolved, unanimously that the Institution be at first a classical and English High School, rising into a College as soon as the wants of the Country demand."

As soon as the wants of the country demand. What a telling phrase.

How did these men respond to those wants of the country? The first president of Wabash, Elihu Baldwin, came from a prominent church in New York City, lured to the presidency by the promise of great deeds. He spoke on July 13, 1836, and his first sentence lays out the program that has occupied Wabash College ever since. Elihu Baldwin said, "The object, fellow citizens, for which we have assembled most appropriately invites our thoughts to the subject of liberal education."

From that time through Andy Ford’s founding of the Center of Inquiry in the Liberal Arts and to this day is a solid line of commitment, passion, and a deep sense of the importance of the liberal arts.

Even beyond the classroom, the heart of the liberal arts quest affects us in every way, most notably in the Gentleman’s Rule and the articulation of the Wabash College mission: a Wabash man will learn to think critically, act responsibly, lead effectively, and live humanely.

At Wabash, liberal education is not a package to be acquired, nor a problem that is solved, but a constantly renewed question, a disposition of the heart and mind as much as a curriculum. The liberal arts mark a way of being in the world, topped off by the Gentleman’s Rule. The men of Wabash own this rule. They recognize that in the defining terms of "citizen" and "gentleman" lies a lifelong project of critical thinking and exploration of ethics, art, and culture reaching for a complete understanding of what it means to be a man.

The dream of the founders of Wabash was uncommon; it was uncommon at its origin because while the founders were men of deep faith, they firmly grounded Wabash in a commitment to be an independent college dedicated to the liberal arts.

An uncommon dream even then, but if anything the dream of the men of Wabash has become even more uncommon as we have endured as one of the few liberal arts colleges for men. Our mission is more relevant than ever, and our service to the common good of nation and world cries out as we articulate this Uncommon Dream for the Common Good.

Let us recast the founders’ questions: What do the wants of the country now demand? What do the wants of the world now demand of Wabash College, of Wabash men?

Let us recast the founders’ questions: What do the wants of the country now demand? What do the wants of the world now demand of Wabash College, of Wabash men?

When throughout the United States boys and men often lag behind in their achievement of higher education, can Wabash and its success in the education of men provide solutions?

We have more to learn, we have much to teach.

When, in cultures around the world, masculinity is viewed more as a pathology than a virtue, Wabash has guided men to the realization of what it means to be a leader and a gentleman.

We have more to learn, we have much to teach.

When the fraternity system at many colleges is in disarray, and Wabash has found ways to enrich the responsibility of men living the fraternal ideals in new and profound ways.

We have more to learn, we have much to teach.

When sports are increasingly professionalized as an apprenticeship to a high-paying career or trivialized into mere exercise or fitness, Wabash athletics offers models of being an athlete and a man, the virtues of the team, and the highest ambitions of sport.

We have more to learn, we have much to teach.

When colleges throughout the country are working hard to draw men from the broad diversity of American life and from around the world to their campuses, we’re proud of the success and growth of our Malcolm X Institute of Black Studies; the proven record of Unidos Por Sangre; and the new life in our growing international student populations—the ways in which the education of all is enriched by the cultivation and honoring of difference.

We have more to learn, we have much to teach.

When throughout the country we wonder about the teaching and learning in the liberal arts, Wabash—through the National Study of Liberal Arts Education and the Center of Inquiry in the Liberal Arts, and the pioneering Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning in Theology and Religion—has much to teach ourselves and the larger world about the age-old questions:

What is the knowledge most worth having?

How do we know that we know?

How must we live?

We have much to learn, and much more to teach.

The best way I know to fail is to live in fear of action.

Tradition at Wabash does not mean inertia—a repetition of the past. We honor the past not by repeating what these men of our history did. They were pioneers; they demand that we be pioneers. We honor them most not when we try to do only what they would have done, but when we attempt to live as they lived, to dream as they dreamed. We honor them most when we embrace our time and our age with the vigor, the energy, the pride, the confidence, and the willingness to fight harder for what is right.

Wabash has a tradition, but that tradition also is paradoxically a tradition of change and innovation.

Men of Wabash, we can shake the world. Men of Wabash have done so for 175 years, and we must do so in the future. We will find a way to be engines of equality in a world of inequality; to be agents of peace in a world at war; to be makers of complexity and careful thinking in an age that wants to replace thinking with slogan saying. We can exude empathy and caring in place of selfishness and obliteration. In a world that cares less about reason, we fight for discourse and argument. In a world that values popularity and acclaims notoriety, we fight for the praise and the honor that comes to good men worthy of respect. In a world of inhumanity, we boldly proclaim our commitment to live humanely.

We are a small College, and many in America and in the larger world may neither note nor care what we do here, but the world needs Wabash and our education. The wants of the country demand our achievements and our leadership. A lot is riding on our good work.

So men of Wabash, I turn to you in hope, with courage, with all the powers and energy I can muster, and I promise you that together, my brothers, we will carry this College we love so well to new heights of service, new heights of honor. We will ask the difficult questions of our times, and we will never tire. In our uncommon dream—the uncommon dream of Wabash College—lies the common good of our country and our world, and we will pursue that dream with our whole heart, our whole mind, and our whole spirit.

Wabash Always Fights.