Tom Kometani ’56 stood at the edge of a dried-up Northern California alfalfa field in 1988 and struggled to find his bearing

Tom Kometani ’56 stood at the edge of a dried-up Northern California alfalfa field in 1988 and struggled to find his bearing

The 12’ x 20’ room he’d lived in as a seven-year-old boy with his parents and three siblings had disappeared. The army cots, bare light bulb hanging from the ceiling, and potbellied coal stove that never gave off enough heat had been hauled away or destroyed.

Long gone were the communal bathhouse, the latrines, and the military-style mess hall, the clanking of metal utensils against tin trays. Gone, too, were the sentry towers where soldiers stood guard over more than 18,000 Japanese American men, women, and children.

Forty-five years later, all that remained of the Tule Lake War Relocation Center—one of the most notorious Japanese American internment camps—were a few old foundations and the skeleton of the Men’s Project Jail—the camp’s prison within a prison.

The one unchanged landmark was the jagged profile of Castle Rock, the mountain Kometani had sketched as he gazed out through the barbed wire more than four decades earlier

"I used to draw that mountain all the time," the retired Bell Labs chemist says. "I remember just what it looked like from our barracks."

So Kometani and his wife Janet walked through the shriveled alfalfa until the profile of the mountain the man saw with his eyes matched the image in his memory.

"It was here," he announced, staring across the open ground at the promontory more than a half-mile away. This was the place where Tom Kometani and his family lived after being taken from their home in Auburn, Washington, in 1942. This was the place where, as the son of a man stripped of his livelihood and his civil rights, Kometani lost his own sense of being an American.

And this is how he got it back.

Tom Kometani rarely complains. It’s partly his nature, partly his father’s teaching. He considers his family lucky compared to those Japanese Americans forcibly taken to the Santa Anita racetrack in California, where four to six people were crammed into the stalls once reserved for horses.

Within months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, soldiers removed Japanese Americans from "exclusion zones" up and down the West Coast in accordance with President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Almost 70 percent of those were American citizens; many were escorted amidst scorn and threats from their neighbors.

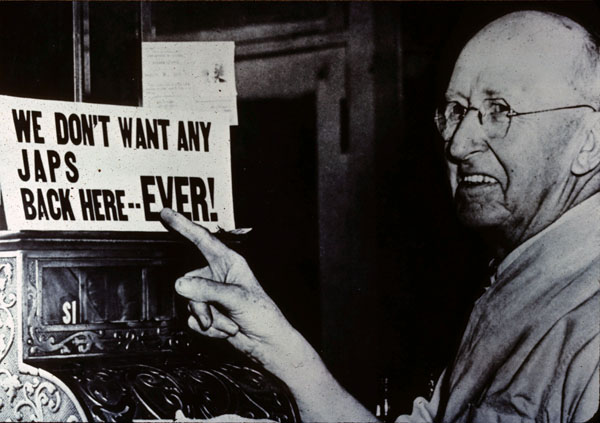

Kometani displays a photograph of people holding up "Get Out!" signs as Japanese Americans are trucked away. He says newspapers stoked the fires of fear and prejudice. He shows the front-page headlines of a 1942 California newspaper. "Ouster of All Japs Near" reads the tag for the story on internment camps. Another headline reads, "Allies Face Japs in Java."

"One story reports on Japanese Americans, the other on the enemy in the war. But in the newspaper, they’re all ‘Japs,’" Kometani says. "I still cringe when I hear that word."

Tom Kometani’s father, Kizo, immigrated to the United States at age 13. Tom’s mother was born in Bellevue, Washington. But "whether you were eight years old or 85 years old, if you had one-sixteenth Japanese blood, you were taken away," Kometani says.

In the spring of 1942, soldiers posted a notice in the Kometani’s Auburn neighborhood giving the family only a few days to sell or rent at sacrifice prices the house and service station Kizo Kometani had worked half a lifetime to earn.

In the spring of 1942, soldiers posted a notice in the Kometani’s Auburn neighborhood giving the family only a few days to sell or rent at sacrifice prices the house and service station Kizo Kometani had worked half a lifetime to earn.

"My dad called us around the table and explained we would have to leave our home, and that we were only allowed to take what we could carry with us.

Deemed "a threat to national security" along with 120,000 other Japanese Americans, they were taken first to the fairgrounds outside of Fresno, California, then on to Tule Lake.

"The first seven years of my life, I thought I was an ordinary American boy. I’d go to school, salute the flag, say the Pledge of Allegiance. I didn’t think there was any problem with us.

"Then came the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the world fell apart for us."

Kometani still recalls the looks on the faces of his fellow internees when they first arrived at the camp.

"People were shocked. We entered a barbed-wire compound between guard towers with searchlights and sentries with machine guns. It was as though we were being put into prison."

First at Tule Lake, and later when they were moved to a camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, the Kometanis struggled to keep their family together and provide the illusion of normal life. The fact that Tom Kometani looks back on many of his days in the camps with some fondness pays tribute to his parents’ efforts and a boy’s imagination."

Yet he can’t forget the chaos of having to line up for everything, the alarm he felt reading warnings that he’d be shot if he walked outside the fence, and the barracks without running water.

He remembers how cold it was in the makeshift schools, and the strange ironies of planned patriotic activities.

"Every Saturday morning we would march with the American flag, as if we were Americans who just happened to be cooped up in this place."

There were sporting events and Boy Scout outings. Kometani recalls a particularly strange Cub Scout program.

"It was a minstrel show. We were all in black face doing hand motions and singing, ‘Oh Susannah.’ It never occurred to me at the time that this wasn’t the right thing to do. I remember them burning cork and rubbing it on our face."

But after the family was moved to the Heart Mountain camp, scouting provided one of Tom Kometani’s favorite moments.

"My father and I went on an overnight camping trip, within the confines of the camp, of course. He and I slept in the same tent. It was the first time I was able to have my father all to myself. That is a wonderful memory for me."

Heart Mountain also had a small pond that, when frozen over, became a skating rink.

"We ordered skates for me from Montgomery Ward," Kometani remembers and smiles. "I was never very good, and they didn’t fit very well." He jokes, "I’ve got bad ankles today, and I still kind of blame them on those skates

"There was an old swimming hole there, and after we swam, we’d take along raw potatoes and cover them with mud, then throw them into the coals of the fire we built. You had to have the right coals." Kometani laughs. "I remember eating some potatoes that were kind of raw."

But even in the midst of such boyhood adventures, the sense of shame and confusion lingered. Kometani holds up a 1942 photograph of a Japanese American boy looking up at American GIs holding weapons.

"The first time I saw this picture, I identified with that little boy, because that’s the angle I saw things from then. Soldiers guarding us, wearing combat gear, carrying guns. I remember thinking, These are American soldiers, and I’m an American. Why are they guarding me?"

Kizo Kometani had his own way of coping with the humiliation, powerlessness, and shame he felt being imprisoned in his adopted country.

"At Heart Mountain it got very cold and there wasn’t always enough coal for the stoves. So when the trucks would come to dump the coal, people would riot as they scrambled for the largest chunks. Dad, being somewhat

"He drew himself into the picture. He’s the man standing over the empty bucket. He’d wait until everybody got theirs, and then gather what was left."

By 1945, all of the War Relocation Centers had closed. Some of the last residents of the camps, mostly the elderly, were evicted, and found themselves homeless, jobless, and virtually penniless.

The Kometanis were among the fortunate—Kizo Kometani had found work earlier in Marengo, Illinois, where the president of the Curtiss Candy Company recruited men from the camps to work on his farms and in his factories in Chicago.

For then nine-year-old Tom, freedom from the camp was a mixed blessing. The farmhouse in Marengo was in poor repair with a hand pump for water, no indoor bathtub, and an outdoor toilet. In a way, it was more primitive than the camps.

"In the camps, I had friends to play with, so, for me, the toughest part came after we left. I thought people on the outside considered me unworthy of being an American, that they considered me the enemy. I started questioning my own identity; I hated being of Japanese extraction. Kids called me ‘Jap.’ It was a tough adjustment.

But there were kindnesses as well.

Gladys Hance, his teacher at the one-room schoolhouse, would often pick up the Kometani children as they walked to school. She invited them to attend the First Baptist Church in Marengo.

"Dad was a little hesitant at first—we were traditionally Buddhist. But he was open minded, and the nearest Buddhist temple was in Chicago, so all four of us kids would be picked up by Bonnie and Don Marshall every Sunday for church and Sunday school.

"I learned later that there had been some discussion about us before we came to town. We were the first Japanese Americans most of them had ever seen in person. We were like the enemy living amongst them. They kept referring to us as ‘those Japanese who live nearby.’

"But the people from the church stood beside us and welcomed us, and that took courage. I owe a lot to those people in Marengo."

Still, his father’s warnings stayed with him.

"He’d say, ‘Don’t ever disagree with anyone unless you’re absolutely certain that you’re right.’ There weren’t many times I was absolutely certain about anything," Kometani says and laughs. "So I didn’t disagree with anyone."

That philosophy seemed to serve him well in post-World War II America, even through his Wabash days. That is, until Professor of Chemistry Ed Haenisch rarely soft-spoken—confronted the amiable, well-liked chemistry major.

"He said, ‘Tom, you’re too quiet. You don’t have to be nice all the time. You’ve got to speak your mind.’

It would take 30 years for those words to finally sink in.

Kometani was in his 40s—a quiet, amiable man and a successful chemist at the Bell Labs, living in a mostly white suburb in Warren, New Jersey—when the American Citizens League began to get a foothold in its efforts to gain redress for the civil rights violations committed during the war.

About the same time, Kometani noticed that people who had always considered his kids "just like everyone else" seemed to experience a subtle but undeniable change in attitude as they reached dating age.

Reading about the poor conditions in the camps and memories of his own experience there of the indignities his parents had suffered began to converge. He realized that his father’s "don’t rock the boat" philosophy had not served him well. Ed Haenisch’s words came back to him. He had to speak out.

"The more I learned, the more I wondered, How could this happen in a country where the Constitution guarantees our individual rights? Kometani became an active lobbyist for a bill apologizing for injustices against Japanese Americans and granting reparations to the 60,000 surviving internees—a legislative battle others had begun in the late 1960s.

As a leader in the New York chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League for almost 15 years, Kometani lobbied legislators, testified before Congress, and appeared on ABC’s Nightline and the MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour.

He lost friends along the way.

"Some people I thought were friends didn’t like my speaking out. But for every friend I lost, I found many others who appreciated my efforts and stood right by me."

In 1980, Congress formed a commission to study the issue, and in 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, apologizing for the injustices and providing a redress of $20,000 for each surviving detainee. As important, President Reagan made a formal apology to the survivors. Kometani attended a reception at the Capitol the day the bill was signed.

In 1980, Congress formed a commission to study the issue, and in 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, apologizing for the injustices and providing a redress of $20,000 for each surviving detainee. As important, President Reagan made a formal apology to the survivors. Kometani attended a reception at the Capitol the day the bill was signed.

"It was one of the greatest days of my life," he recalls. "Finally, the government admitted it had made a mistake and actually gave reparations. And that token amount was important—without the dollars, the apology would have been buried in the Congressional Record somewhere."

Kometani struggles to keep his emotions in check when he remembers that moment.

"I was very proud of being an American that day. I felt that this was the America that is and could be, and that day was proof for me. Part of the genius of the Constitution is that it can accommodate changes in attitude. It can accommodate justice."

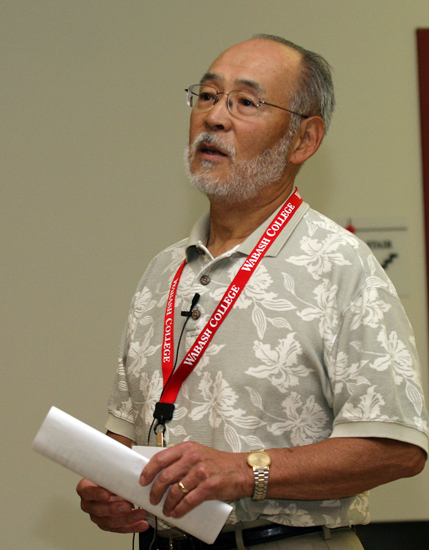

Now 72 and living in Washington, the state he was taken from as a child, Kometani returned to Wabash last June to tell his story at the College’s Big Bash Reunion Weekend. He spoke in Hays Science Hall, which has a reading room dedicated to his mentor, Ed Haenisch. It was the first time most of his Class of 56 classmates had heard about his experiences in the internment camps. He hadn’t been eager to talk about it during his Wabash years.

But many of his classmates thanked him for telling the story that day. Ed Haenisch would have been proud.

For Kometani, reclaiming his sense of being an American meant more than accepting an apology from the President; he believes he has a responsibility to speak out when necessary. He told classmates he was wary of some provisions of the Patriot Act. He’d noticed something eerily familiar in the public’s response to Arab and Muslim Americans in the days following the attacks of 9/11.

Tom Kometani knows firsthand what it’s like to bear physical resemblance to the enemy. It’s burned into his heart and mind as indelibly as that jagged profile of jagged profile of Castle Rock he used to draw as a boy.

"The price of our freedom is vigilance," he told his classmates. "Don’t think it couldn’t hapen again."