LESLIE HUNT WAS LIVING the latest version of the American Dream when her father had a nightmare.

LESLIE HUNT WAS LIVING the latest version of the American Dream when her father had a nightmare.

The vision came to Steve Hunt ’76 during Leslie’s run last spring as the "token artist girl" on season six of Fox Television’s top-rated American Idol.

The specter wasn’t Idol judge Simon Cowell ripping the 25-year-old singer-songwriter to pieces in front of the 41 million viewers who tuned in to see who would become the next Kelly Clarkson or Carrie Underwood in the pantheon of pop music superstars.

Nor was it an anxious image of his daughter missing a note or otherwise melting under pressure. Having battled lupus since being diagnosed with the autoimmune disease as a child, Leslie has taken on more daunting foes than Cowell and his sidekicks.

She brings up the nightmare during my dinner with her and Steve on the porch of the El Pacifico restaurant in Chicago’s Logan Square historic district on a warm summer night in August.

"It was me in this really sleazy outfit, strutting out on stage and looking into the camera and saying, ‘Hey, baby.’ "She laughs.

"Like this competition had completely changed you," he says.

"Like I had become this sleazeball — all Hollywood slime and nothing of substance," Leslie says.

"I told her about that dream a few days before her appearance as one of the 24 finalists," Steve recalls. "I knew she would laugh, and I hoped it would help her keep her sense of humor during a very intense time in her life. And she knows she is nothing like this affected ‘drink your own bathwater’ type of person that I dreamed she suddenly became!"

Flying to Los Angeles to try out for American Idol was more impulse than decision for Leslie. She had never even seen the show.

"I guess I was kind of naive," Leslie says. "I had this ‘what’s there to lose’ attitude."

More than 10,000 singers from around the country auditioned, and Leslie, packed into the Rose Bowl as contestant number 73560, made the first cut—one of 174 to reach "Hollywood Week." Then she made the Top 40, and her rendition of Carole King’s "Natural Woman" earned her a spot among the Top 24 semifinalists.

The emotional stakes ratcheted up with each success.

"I auditioned on a whim, but I developed such high hopes," says Leslie, who has been performing since she was seven years old. Her smoky singing voice belies her 25 years, willowy build, and girl-next-door prettiness. "I wasn’t cocky about it. I just know what I possess, what I’ve been given."

What Leslie Hunt has been given is a soulful voice that can deliver Patsy Cline’s "Crazy" or Gershwin’s "Summertime" on one stage, slide through her own introspective ballads on the next, and then move you with "Amazing Grace" at Arches National Park (courtesy of YouTube) on the next.

She told Idol audiences that, if she won, the first people she would thank would be her parents, "for instilling in me the gift of music."

She dedicated her performance to her late grandfather.

"He was the definition of unconditional love," she said in the clip shown before the performance. "That’s what I carry with me on the stage."

She hit her mark in front of the cheering studio audience and 41 million viewers to sing "Feeling Good," knowing she was taking a giant step toward the dream her father dared not chase—the dream of playing music full time, making a living at her vocation, avocation, and passion.

Back Home in St. Charles, Il., Steve Hunt was calling everyone he knew, telling them Leslie was on television, and encouraging them to vote for her. By day, Hunt is vice president of the architectural division of Northfield Block, the company his father had owned since 1983.

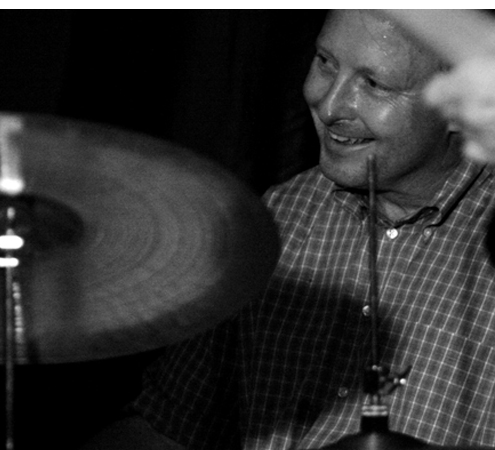

By night, Hunt is "one of the wonders of the world’s drummers."

That’s how Chicago jazz historian and critic John Litweiler describes the former Wabash music major in the liner notes of his group’s latest CD, Extraordinary Popular Delusions. Hear Hunt's jazz and see photos here.

"He has such great sensitivity for ensemble texture and for exactly where to accent," Litweiler writes. "His gestures sound so natural and so necessary."

Hunt carries that same natural ease into conversation. Once the percussionist of the groundbreaking free jazz quintet Hal Russell’s NRG Ensemble, Hunt now plays with former NRG saxophonist Mars Williams and bass player Brian Sand-strom, as well as keyboardist Jim Baker. The group has a standing gig every Tuesday night at Hotti Biscotti, a bar/coffeehouse/music venue on Fullerton Avenue in the historic Logan Square District on Chicago’s near-west side.

Divorced and remarried to his new wife Polly (Leslie and her sister, Lauren, sang

at the wedding), Steve now has six daughters. He has returned to live in the house he grew up in in St. Charles — a home that has always resonated with music. His brother, Jeff, directs the 34-voice St. Charles Singers. His brother, David, who owns the town bookstore, also sings in that choir, along with his youngest sister, Jennifer.

"I love to sing, too, though I’m not near their level," says Hunt, who began singing in the church choir when he was four and was good enough to tour with the Glee Club during his Wabash years. He has sung in various rock bands, but percussion has been his favorite entre to music since grade school.

"I listened to a lot of Beatles music growing up, and in sixth grade I wanted to be the next Ringo," he remembers. "I tied together two toy drums between a TV tray stand, my three friends made cardboard guitars, and we had our first (and only) gig for the end of year sixth grade party. The class voted to see and hear us lip sync along with Beatle songs and have our party inside, instead of playing kick ball!"

"That same year, the school choir instructor, Mr. Stoffel, needed someone to accompany the singers on snare drum.

"That same year, the school choir instructor, Mr. Stoffel, needed someone to accompany the singers on snare drum.

"I really liked drumming, so I raised my hand exuberantly, and he picked me."

By eighth grade, he was the drummer for the Brass Leaf Quartet, earning $8 per night playing Dixieland jazz on the stern-wheeler that plied the Fox River. The trombonist in that band, Jim Masters, is still among his best friends.

"We’d play and the music would just permeate everywhere across the water," Hunt recalls. "The boat owner would tell us, ‘Soft and sweet, fellas; soft and sweet.’"

After high school and a semester at a conservatory, Hunt transferred to Wabash as a music major. There he met pianist/composer Eric Johnson ’76 (pictured above, playing piano with Hunt during their Wabash years).

"We were like soul mates," Hunt says of Johnson, who with bass player Kyle Jones ’78 and saxophonist Andy Murduck ’78 were the core group led by Johnson during his Wabash days. The summer after his graduation, Hunt moved with Johnson, Jones, Murduck, and manager/enthusiast Alex Betz ’78 to Bar Harbor, Maine, where Jones’ family had a house.

When Hunt’s father’s business associate died of cancer, Max Hunt offered his son a job with the family business. Steve took the offer, but brought the band with him.

"We lived in a house outside of St. Charles," Hunt recalls. "I was the only one with a full-time job. Eric was writing music and playing all the time.

They were playing gigs as the Eric Johnson Quartet.

"It was the best of both worlds," Hunt recalls.

Then Murduck was killed in a car accident in the spring of 1977. Johnson moved to New York, Jones returned to Maine to become an attorney and state legislator, and Hunt married Anne Voigtmann, a voice performance major at Indiana University whom he had known since high school in St. Charles.

"I had the best of both worlds when I played with Eric and Kyle, and I have the best of both worlds now," Hunt says. "I can play the music I want to play, not weddings on the weekends or stupid

private parties where I’m playing background music. I can’t play all the time, but when I play, I play music that is meaningful to me."

Leslie Hunt was steeped in that music.

"Family gatherings were all-out sing-alongs, mostly around the piano," Leslie recalls. "I was always singing."

And she was always encouraged.

"It was around the time The Little Mermaid came out. I’d be singing downstairs, and Mom and Dad, knowing I was within earshot, would say, ‘Wow! Doesn’t she sound just like Ariel?’ I got all cocky

about it!"

The basement was a musical recreation room.

"We had a keyboard I’d play, Mom would play bass, and Dad would shout out chords to me while he was playing the drums with my sister Lauren on his lap. We had all these microphones set up, and friends would come over and we’d sing."

In those days her musical influences weren’t Dad’s jazz but the cartoon show Jem and the Holograms.

"We’d dress up in all this hard-core 80s garb, wear blue eye shadow, and Mom would tape us on the video camera while we looked right into it." Leslie can still sing the title song, though not without laughing.

In fifth grade she and her sister were among six kids chosen from 600 to performed in Kenny Rogers’ Christmas show.

"We ran around in fake snow and Kenny Rogers appeared out of this gift box, and we all said, ‘Ooohhhh, Kenny Rogers.’"

In seventh grade she appeared in a year-long run of Fiddler on the Roof in Chicago. In her late teens, her musical influences ranging from Billie Holliday to Joni Mitchell to Nina Simone, she was making a demo CD for Sony. Her dad played vibes on one of the tracks.

But the carefree, creative childhood had a catch.

"I was diagnosed with lupus when I was six-and-a-half, so when I was a kid there were a lot of limitations," Leslie says. "For me, the symptoms were extreme photosensitivity and full-body arthritis. I’d get scabs all over my face if I spent any time in direct sun—I could only go out in the shaded back yard after 3 p.m. I had friends, but not a lot of kids wanted to hang out with someone who couldn’t come outdoors until the sun went down.

"I had to learn to entertain myself."

The basement music room was her refuge. She began writing songs in grade school, and today carries a digital recorder, capturing words and musical phrases, later to be shaped into songs.

"Scrawling out a version of me," as she sings in her 2004 CD From the Strange to a Stranger.

The arthritis still flares up if she doesn’t get eight hours or more of sleep, but two years ago she began taking the anti-malarial drug Plaquenil, which has greatly reduced her photosensitivity. That newfound freedom has its hazards. A reaction to a yellow fever medication during a visit to Brazil last year was nearly fatal.

"I told myself that if I survived that, I could survive anything," she says. "It was time to really go after life, to take a risk."

Less than a year later she was auditioning for American Idol.

Steve Hunt watched his daughter’s American Idol semi-finals performance with pride, wonder, and frustration.

"It’s a new dawn. It’s a new day. It’s a new life," Leslie sang, delivering Nina Simone’s signature song, "Feeling Good."

"She nailed it," Steve Hunt says. "She sounded so good. Her version was fully valid, fully real."

But Randi Jackson called it "a little on the kitschy side." Paula Abdul liked it, but her inarticulate ramblings are often little more than fodder for Cowell’s acidic remarks.

The record executive turned to Leslie. "You’ve been whacked by three or four very big voices [that performed before you]," he said. The camera caught her reaction. Her expression was part startle, part disappointment. She listened to the words that, for all practical purposes, eliminated her from the competition.

"I’m watching this and, as proud as I am of her, I was getting very frustrated with the fact that the judges just didn’t get her," Steve says. "And the judges’ comments have a lot to do with how people vote."

Leslie drew millions of votes from viewers, but not enough to propel her to the next round.

"I feel she really didn’t get the visibility on the show that she deserved," Steve says. "Had she gone even one more week, the outcome would have been completely different."

She’ll laugh about it now, but the experience still stings.

"Think about a national rejection," she says. "Or think about America not wanting to see you week after week. It’s a strange feeling. Like you’ve become a has-been before you’ve had a chance to show anybody even one-percent of what you’re capable of."

"And it would be one thing if the judges gave me any practical advice," Leslie adds. "Given that I am attacking a career in this business with every bone in my aching body, perhaps I could have learned something, had they said anything but, ‘I wasn’t feeling it.’"

I point out that four million people did vote for her, and that such an affirmation is more than most of us will ever get.

"I never thought about it that way," she says. "In some ways, it’s good I didn’t make it. I might have lost my ability to trust my own vision. It could have taken away whatever integrity I have. It really wasn’t my vision at all."

What began as a personal quest to promote her career is becoming a good thing for millions whose struggle Leslie knows well.

"It’s brought me some great opportunities locally, particularly with the Lupus Foundation. I’m playing several events for the them here in Illinois, but the guy who is setting up the event in Florida sees it as something bigger, something nationwide."

Six months after her final appearance on Idol, she’s put together a new band with some of Chicago’s best players, is at work on a new CD, is performing to larger audiences, and is seeing new purpose for her work. During an interview before the semi-finals, she told a reporter that her "real objective is to be in a position to help the Lupus Foundation."

And that’s exactly where she is.

BACK AT EL PACIFICO IN CHICAGO, it’s the night of the CD release party for Steve’s band. Father and daughter are recalling Leslie’s early songwriting.

"Do you remember the first song you wrote?" I ask.

"I was seven or eight," she says. "It was all about why you should be kind to all your stuffed animals, even the ones you hate."

She sings a verse of it, and Steve leans toward her and harmonizes on the chorus. They laugh, and Leslie instructs me not to print the lyrics in this story.

She’s been searching for a drummer for her band, and when I suggest her dad, they both laugh again.

"I’ll always have a thing for jazz because of what I learned from my Dad," Leslie says.

"And I did play drums on the stuffed animal song," Steve says.

"The Hunt Band," Leslie says. "We never took it on the road."

But Dad did hit the road with her this summer on a day trip to Nashville when she was looking for a producer for her next CD.

"I’ve got to learn the business, how to make this really happen—finally," Leslie says.

TEN MINUTES BEFORE THE CD release party, I ask Steve what he thinks of Leslie’s chances of making it in one of the toughest careers on the planet.

"With her talent and confidence, she’s got to try," he says. "There are plenty of good people in the music business—she just needs to find them. And a good lawyer, so she doesn’t sign something she regrets."

He knows the odds. He once made his own calculations—albeit in the far less lucrative genre of free jazz—and chose not to go for it. But he’s 100 percent behind his daughter now.

"If she can do what she loves and make a living at it, wouldn’t that be great?"

Keyboardist Jim Baker sticks his head out the door. It’s time to get started.

Five minutes later, Steve kicks off the set. "Preternatural" is the word one critic uses to describe the way these musicians play off one another. John Litweiler writes that "in reflection, in the heat of passion, and in their moods between, their intensity of listening, feeling, and responding makes their quartet amazing."

Leslie is watching from a few tables back, sitting next to a family friend from one of Steve’s earlier bands. Several more old friends and many much younger walk in during the first number. Her younger sister Lauren arrives and Leslie hugs her. After a few minutes they’re playfully imitating their father, who is rocking back and forth in reverie as the first set winds up.

Leslie is watching from a few tables back, sitting next to a family friend from one of Steve’s earlier bands. Several more old friends and many much younger walk in during the first number. Her younger sister Lauren arrives and Leslie hugs her. After a few minutes they’re playfully imitating their father, who is rocking back and forth in reverie as the first set winds up.

Watching Steve play the music he loves with these friends he’s played with for decades brings back Leslie’s words to him earlier that evening: "I think it’s great that you never really have to take gigs because your bills depend on it—that you play only the music you love to play."

At that moment, it’s hard to imagine a man more content. His daughters are in the audience and he’s sitting at the back of the band, cueing Williams or Baker one moment, closing his eyes and smiling the next, his drums keeping it all together.

The best of both words.

Read more about Leslie Hunt’s music at www.myspace.com/lesliehunt