Excerpted from a talk

—by Philip Caputo, 2007 Will Hays Writer-in-Residence

Every day, the news media bombard us with facts, many of which later turn out to be untrue.

Every day, the news media bombard us with facts, many of which later turn out to be untrue.

Astrophysicists trot out new models of the cosmos faster than Microsoft or Apple markets new operating systems, thus turning the old models, previously accepted as valid, into creation myths. A medical study presents as gospel the beneficial effects of a new drug; then a subsequent study proves beyond doubt that the drug is not beneficial, but is, in fact, harmful.

All this fluctuation, this constant altering of what’s true, is bewildering. We are confronted daily with the unsettling realization that the "facts" we embraced last year or last month or only yesterday were illusions, and our belief in their veracity was, therefore, little more than superstition.

It is especially bewildering for the writer, making it difficult for him or her to stay focused. Focused on what? On human nature. The truths of human nature don’t change, which is in itself a truth both comforting and disturbing. As Faulkner said, the human heart in conflict with itself is the writer’s subject, and the emotions that move and rive the human heart—love and the need to love, hate and the need to hate, greed, ambition, pride, fear, jealousy, pity, cruelty, courage, cowardice—have done so probably ever since some hairy biped rose up off its knuckles to stride upright across the African savannas.

The circumstances that give rise to human emotions and conflicts change drastically, but the feelings and the conflicts themselves are the same. Put Flaubert in a supermarket checkout line and he will find Madame Bovary in some bored, dissatisfied young woman as she gazes with frustrated longing at the glamorous faces looking back at her from the covers of celebrity magazines. Put Stephen Crane in Iraq and he will find Fredrick Henry in some resolved but frightened soldier patrolling the streets of Baghdad. Conversely, put a copy of Madame Bovary in the hands of that young woman and she will recognize herself; let the soldier in Iraq read The Red Badge of Courage and he will see himself.

All of my writing career—it will be 40 years next year—I’ve been both a novelist and a journalist. You could say that I have a foot in both worlds, but that would set up a false dichotomy. In me, the realms of fact and fiction, of the empirical and the imaginative, occupy the same mental space at the same time, and sustain each other.

In the spirit of the new journalism, which is anything but new today, I’ve used the techniques of fiction in writing nonfiction. My first book, A Rumor of War, has often been mistaken for an autobiographical novel because of its structure and dramatic tension, but it is a memoir, as factual as my memory could make it.

On the other hand, the reporting I’ve done as a newspaperman and magazine writer has often planted the seeds for my novels. My first one, Horn of Africa, grew out of an assignment for the Chicago Tribune in 1975, covering the Eritrean rebellion in Ethiopia. I have also found that the skills acquired as a journalist are useful in researching a work of fiction. Sometimes, the information I pick up can be recycled into journalism. For example, I filled a half-dozen notebooks and twice that many file folders in researching the novel I’m working on now—Crossers. It is set on the U.S.-Mexican border. In the midst of writing it, the Virginia Quarterly Review asked me if I could contribute 10,000 words to an issue they were devoting to the border situation. So I set the novel aside for a time, and transited out of the imaginary world I was creating into the real world, and did not suffer the equivalent of culture shock.

I’ll mention in passing that I am careful not to confuse the two genres. Ever since Tom Wolfe penned his Kandy-Colored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby and Truman Capote his In Cold Blood—the urtexts of the new journalism—a lot of nonsense has been purveyed in journalism schools, generally under the course title of "creative nonfiction." All too often this form of journalism is the last, or first, refuge of charlatans who take creativity as a license to tell whoppers under the guise of telling the truth. That violates the bond of trust between the writer and the reader, who has a right to expect that the author is presenting a tale of factual accuracy. Capote himself was guilty of manufacturing entire scenes and conversations, and made millions off his fraudulence. Which didn’t make it right.

So let’s say that when it comes to fact versus fiction, I believe in the separation of church and state. My fifth book, Means of Escape, was a kind of experiment to see if that separation could be maintained in a single work. It was to be a memoir of my years as a foreign correspondent in the Middle East, Vietnam, East Africa, and other third-world hot spots. Now, a memoir is the tale memory tells, and my memory of events like the October war in Israel, the fall of Saigon, and the Lebanese civil war was as smudged as my old notebooks—smudged by the passage of time so that parts of it were illegible or barely legible. And I was aware of an observation Schopenhauer once made—that what Peter says about Paul says more about Peter than it does Paul. So, too, a memoir says more about the way its author is now than he was then. But I did my best to remember things and myself as they and I were rather than as I wished them to have been.

I was well into it when I began to sense that something was missing, some quality of what the places and the times felt like—the weirdness of Vietnam, the deadly chaos of Beirut, the anguish and dread that marked the birth of the age of terror. My notebooks and my memory were full of disconnected episodes that didn’t fit in with the main narrative. I hit upon the idea of shaping these isolated incidents into sketches that would appear as interludes between the autobiographical chapters. As I wrote them, I realized that capturing the emotional truth I was after required some fiddling with remembered experience—a certain rearrangement of fact, if you will.

I was well into it when I began to sense that something was missing, some quality of what the places and the times felt like—the weirdness of Vietnam, the deadly chaos of Beirut, the anguish and dread that marked the birth of the age of terror. My notebooks and my memory were full of disconnected episodes that didn’t fit in with the main narrative. I hit upon the idea of shaping these isolated incidents into sketches that would appear as interludes between the autobiographical chapters. As I wrote them, I realized that capturing the emotional truth I was after required some fiddling with remembered experience—a certain rearrangement of fact, if you will.

I had, and trust that I still have, a fairly high standard of professional ethics, inculcated long ago in the Chicago Tribune’s newsroom. I recall the time when, as a cub reporter, I’d interviewed an Estonian immigrant whose daughter had been raped and beaten on the North Side. I wrote something to the effect that Mr. So-and-so felt angry and betrayed by his adopted country. The night city editor called me over to the copy desk and asked, "What do you mean, he felt angry and betrayed? How do you know that?"

"That’s what he said," I answered.

"Then that’s what you write," the editor shot back. "Mr. So-and-so said he felt angry and betrayed.’"

Given that rigorous training, I knew there were liberties I could not take. I did not want to hoodwink anyone into believing that the vignettes were precise records of what happened, so I distinguished them from the factual parts of the narrative by titling them "Disasters of War," after Francisco Goya’s pen and pencil sketches from the Pen-insular War in Spain. Also, I took pains in the introduction to tell the reader that my sketches were at least partly invented, were semi-fictional pieces composed to achieve an artistic effect.

Well, you do that sort of thing at your peril. Critical reactions were mixed. Reviewing Means of Escape in the New York Times, Morley Safer took me to task for fogging the boundaries between the real and the imagined. The late Harrison Salisbury, however, in his review for the Chicago Tribune, thought—or shall I say, wrote that he thought—that the sketches were somehow truer than the "true" passages.

Ezra Pound, a man who I understand spent some time at Wabash, said somewhere that literature is news that stays news. News, as we understand the word, is by its nature evanescent—there is nothing older than yesterday’s headlines, or, in this age of 24/7 coverage, the headlines of an hour ago. How to make it stay, how to find in the swift passage of events what is enduring, is the thing I’m always after.

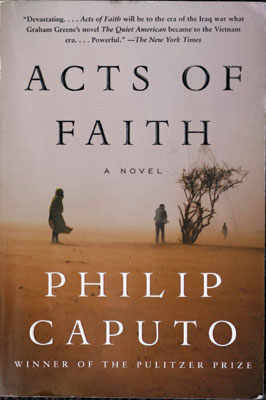

Philip Caputo shared a Pulitzer Prize when he was a reporter for the Chicago Tribune. His memoir A Rumor of War has become a classic, and he is the author of 10 other books, including his most recent novel,

Acts of Faith.

In October, he was the 2007 Will Hays Writer-in-Residence at Wabash.