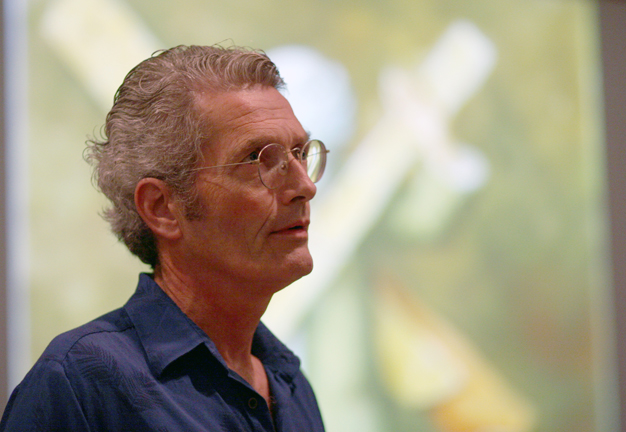

Biblical critic and Wabash Dean of the College Gary Phillips believes the art of Samuel Bak should not only change the way we read the Bible, but also reshape the questions we ask about God and suffering.

Biblical critic and Wabash Dean of the College Gary Phillips believes the art of Samuel Bak should not only change the way we read the Bible, but also reshape the questions we ask about God and suffering.

A Holocaust survivor whose family was forced into the Vilna, Lithuania Ghetto after Germany invaded that country in 1941, Bak exhibited his first paintings there at the age of nine in the midst of massive executions perpetrated by the Nazis and their Lithuanian collaborators.

In presentations on Bak’s work given Thursday at Keene State University and at the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting in Boston this weekend, Phillips and his co-author, Drew University Professor of the Hebrew Bible Danna Fewell, portray Bak’s 70-year body of work as "art that entrances, [but] also disquiets."

They describe repeating elements in his paintings: "Dismembered human figures of flesh, metal, wood, and stone; broken pottery and rusted keys; petrified teddy bears and discarded children’s shoes; floating rocks, and uprooted trees. Broken chess pieces. Fractured rainbows. Soundless musical instruments, flightless doves, mechanized, immobile angels, crucified children."

And yet, Phillips says, there are also images of "new growth on broken branches, sunrises in sunsets. Genesis and genocide. Ruins and remnants. Paradoxes. Contradictions. Ambiguities. Excesses. All ingredients of a survivor’s post-Holocaust landscape."

Bak’s art, Phillips says, challenges convenient or traditional answers of both believers and skeptics to the question, "Why do the innocent suffer?"

"The Jewish philosopher Irving Greenberg has written that ‘no statement, theological or otherwise, should be made that would not be credible in the presence of burning children,’" Phillips said. Bak’s art keeps those faces in front of him as he interprets the Old and New Testament and contemplates his own theological questions.

Phillips and Fewell wrote the catalog for the artist’s exhibit at the Pucker Gallery in Boston in October, and they’ve co-edited, with Yvonne Sherwood, Representing the Irreparable: The Shoah, the Bible, and the Art of Samuel Bak, published last May. They also have befriended the artist, becoming part of a conversation that not only informs their scholarly work, but Bak’s latest paintings.

Phillips and Fewell wrote the catalog for the artist’s exhibit at the Pucker Gallery in Boston in October, and they’ve co-edited, with Yvonne Sherwood, Representing the Irreparable: The Shoah, the Bible, and the Art of Samuel Bak, published last May. They also have befriended the artist, becoming part of a conversation that not only informs their scholarly work, but Bak’s latest paintings.

"Bak’s work had already taken up pieces of the Biblical text before we met him," Phillips explains. "But in conversation with us, he’s begun to do more. Our becoming conversational partners had a double benefit. We were mining his work for help in reading Hebrew and Christian texts in a different light, shaped by the experience of the Holocaust, while he was going back to his artwork and exploring themes related to the Bible and religion that had been there, but had not been articulated."

Two results of that conversation: Phillips and Fewell’s book, which came out of a series of conference papers related to the intersection of Bak and the Bible in light of the Holocaust; and a flurry of Bak paintings of the "Ghetto Boy," based on a photograph taken in the Warsaw Ghetto.

"There were maybe 19 or 20 of these paintings, but now there are nearly 80," Phillips says.

"We have become invited guests into the gallery to put together these catalogs, which are labors of love," Phillips says. "But also we increasingly feel like part of the family, a resource for them—we help articulate Bak into the academic community, at the same time learning a great deal from him.

"But we’re dealing with issues that go beyond the scholarly and artistic community," Phillips explains. "On Monday night we’re meeting at the Pucker Gallery with a number of people from the Boston area who have taken up the issue of children and their welfare. The gallery owners, Bernie and Sue Pucker, are taking this up as a calling — a citywide effort to address the needs of children."

In terms of the theologian's scholarly work, Bak’s creative response to the Holocaust has transformed the way Phillips thinks about Biblical texts he had studied his entire academic career.

"When we read the first chapter of Genesis with Bak’s imagery in mind, we are invited to… imagine a very different story than tradition has allowed."

Phillips calls the new way of seeing that Bak’s work inspires a "parallax." A term more common to astronomy, a parallax is that shift in perception you notice when you’re looking at an object, you close one eye, then quickly open it and close the other.

"You need both views for depth perception," Phillips says. "Bak’s work coming out of the Shoah enables you to see the object of the world differently by contrasting the view you normally have with the view he has," Phillips explains. He believes seeing Bak’s work provides a sort of depth perception in understanding.

"His art has led us to think about authorship of the Bible as emerging out of and in responses to some historical moment of trauma or crisis. For the Hebrew Bible, that moment is the Babylonian exile. For the Christian Testament, particularly the Gospels, it’s the Roman War of 67 to 70. Both of these traditions are shaped by trauma—concrete historical moments in which there are real human beings whose experiences have been torn apart and patched together. That experience is instructive to the way these testaments are put together."

The cover of Phillips’ book features a Bak painting entitled "Memorial" that serves as a metaphor for this patchwork.

"Bak’s work is, at some basic level, about the power of the question—the power of his paintings to reshape the questions we ask about God and suffering," Phillips adds. "The question becomes not, ‘Why does God permit suffering?’ but ‘What steps can I take now to intervene in the suffering of another?’ ‘What’s the phone number of the local clinic?’ ‘The local family shelter?’ ‘What question do I ask of officials to hold them accountable?’"

Dean Phillips and Wabash will welcome Samuel Bak and his work to campus on March 2 in the Eric Dean Gallery of the Fine Arts Center.

In photo: "Memorial" by Samuel Bak; Dean of the College Gary Phillips