The Gentleman’s Rule is an ever-elusive thing when you attempt to put it into practice in the real world.

In my parents’ home in Crown Point, IN, only one Wabash image hangs as a reminder of the days my older brother Chad and I spent doing “air-raids” in Mud Hollow, chatting up Coach Max Servies at the Scarlet Inn, eating a fried peanut butter sandwich at the Snacker, and shooting pool at Tommy’s.

In my parents’ home in Crown Point, IN, only one Wabash image hangs as a reminder of the days my older brother Chad and I spent doing “air-raids” in Mud Hollow, chatting up Coach Max Servies at the Scarlet Inn, eating a fried peanut butter sandwich at the Snacker, and shooting pool at Tommy’s.

The image is a pencil drawing. I drew it when I was a junior in high school. It’s a depiction of Chad leaving the field at Little Giant Stadium, battle tested and victorious in a tattered scarlet jersey. The line along the bottom of the page reads “Some Little Giant.”

My brother was small for a football player, undersized even for a Division III defensive back. But Chad played bigger, gave more, and he inspired me. The drawing was a gift to him on the Christmas I decided to follow his footsteps and attend Wabash College.

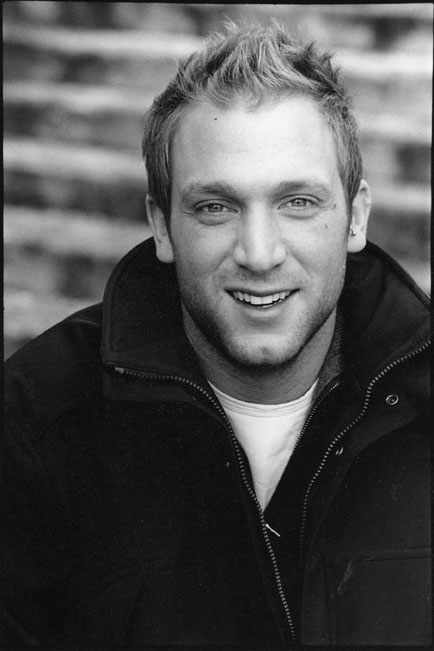

Chad proclaimed that I would get more out of Wabash than he did. He said, “Ty will appreciate the experience more than I did. Ty will embrace the culture, take fewer road trips to chase women, be more involved on campus. Be a better Wabash Man.”

Wabash Man? What does that even mean?

My after-college journey has not been the typical Wabash narrative. Over the past five years I’ve lived in Manhattan. I’ve worked as a high profile bartender in the club scene and the after hours of the urban night.

The money was good, real good, the temptations even better. By my own admission I had lost my way in that place, becoming a follower to the night, a slave to fantasy, a weekend version of the boy that left Crawfordsville just a few short years ago.

When President Ford had rung us out with the Caleb Mills Bell that hot day in May 1999, he urged us to go out into the world, and, above all, be good men. I had failed. I certainly was no gentleman!

My world changed on February 5, 2007. I was awakened by a phone call to my Manhattan Loft—a call too early to bring anything but bad news. This brought worse. My younger sister was on the other line. She was delirious. My niece, Reilly—Chad’s five-year-old daughter— had died.

Reilly had been an exuberant spirit. She had the energy and moxie of that undersized defensive back her father had been in college. She had the intellect of an adult, and the heart of an angel. We later would find out that she passed away from complications of the flu.

No warning. No preparation. No answer.

The next few months were a terrible struggle. I decided it best to leave my life out East for the time being and return to Crown Point to be with family, to offer support, to try to be a good brother. I watched a family paralyzed with grief learn to walk again, slowly, bruised and battle tested, and scarlet tattered.

As the icy February ended, March brought new life. Amidst the depression, the darkness, and nothingness of grief a great deal of hope was born. People who had heard about Reilly’s death began to send donations. The outpouring was overwhelming. Chad and my sister-in-law Michelle decided it best to honor their daughter by starting a foundation that would help terminally ill children and teach others to do the same.

The Reilly C. Bush foundation was born. In less than two years they raised over $100,000 dollars for children in Indiana and Illinois. The projects they are doing today are drawing notice and helping countless underprivileged and sick kids. They are making Reilly proud.

Eight years out of Wabash, I’ve learned that by going into the world you’re bound to fail—it’s inevitable—by taking risks and trying to evolve. The mark of a man isn’t when he falls down, but how he recreates himself—that he finds the courage to get back up when the odds are against him.

The underdog, his brother’s keeper, the Little Giant. As always, Chad has proven himself an excellent example of all three. The loss of his daughter has been the impetus for a rebirth—a rebirth for all of us. Together with Michelle and so many others, he has built a charity on top of grief and has shown us all what it means to be strong, to be a leader, and to serve others with grace and compassion.

This past year I’ve been reminded of what it means to be a gentleman. I now try to move forward to help others. To make the right decisions. To be a man. To re-learn the lessons taught so many years ago.

The Gentleman’s Rule is an ever-elusive thing when you try to put it into practice outside the hermetic environment of the Chapel, Center Hall, and the old Armory. It’s something we have to keep reaching for even in our darkest of days.

So I ask the question once again—to be governed by a rule that is defined by the individual: What does it mean to be a gentleman? How do we become good men?

We fight. After all, Wabash always fights. We fight for those we love —our family, our friends, and for those who cannot fight for themselves.

Maybe Chad was right; perhaps I took more from Wabash than he did. But he is giving back. And from where I stand, all I see is Some Little Giant.