Four nights after 12 Wabash students began teaching teenagers in a run-down school in one of Quito, Ecuador’s roughest neighborhoods, the lights went out.

“The high school students are yelling in Spanish, and their voices are bouncing off the walls, because there’s no sound insulation in these concrete-block classrooms,” Professor of Teacher Education Deborah Butler remembers. The Wabash students did their best to calm their charges—Michael Jordan ’11 used his cell phone as a flashlight. And Professor Butler was still wondering what could go wrong next when Alex Avtgis ’11 approached her calmly in the midst of the cacophony with a question: “Do you know any language games we can play in the dark?”

.jpg)

The lights came back on minutes later, but Butler sees the blackout, as well as the response of the Wabash men and the two DePauw women in the program, as a metaphor for this first teacher education module for the College’s Summer Study in Ecuador program.

So many surprises—testing the students’ mettle and patience, resilience and adaptability, not to mention their convictions and determination to make a difference. Which is why this year’s Ecuador program may have been the best yet.

What’s Next?

“We learn immediately that nothing is what it seemed,” Butler wrote in her journal the day she arrived in Quito.

Wabash students had been in the city for three weeks, living with host families, ratcheting up their language skills, adapting to the Ecuadorian culture and cuisine. Now it was time to begin to teaching, to put to the test the lesson plans and activities they’d worked on in class back home.

Their first surprise: They’d be teaching not in the cozy, classy Centro de Formacion (with its high walls topped with broken glass to keep out intruders), but in the high school blocks away, with concrete echo chambers for classrooms that had cracked and broken windows and one blackboard facing 45 to 60 desks per room.

They’d be teaching the night shift.

And the lesson plans? Throw them out; the high schoolers lacked the basic English skills needed for almost all the activities planned for them.

But these 12 students picked from 30-plus applicants had not been chosen for this class because they were teachers—only two were even in the teacher education program. They’d been selected, in part, because of their desire to serve and ability to adapt to difficult situations. Professor Butler was about to find out whether she and the other program faculty, Spanish Professors Dan Rogers and Jane Hardy, and Assistant Professor of Teacher Education Michele Pittard, had chosen well.

“A Bone to Pick”

“I have a bone to pick with our education program,” Victor Nava ’10 told Butler on his second day teaching in Quito. “Nowhere in our methods courses did I ever learn how to teach in the dark or what to do when students bring their babies to class.”

“Well, what did you do?” the professor asked.

“Asked the baby’s name as we all introduced ourselves, and we just kept talking and trying to learn,” Nava said. When the noise from all of the other rooms made conversation impossible, Nava led his class outside to an empty unlit room away from the racket.

“He simply taught them in the dark, with enough ambient light to see one another,” Butler explains.

When the school’s science teacher didn’t show up one night, school officials asked for a volunteer to teach the class.

“We had Patrick Garrett ’12, who’s in biology, and Josh Johnson ’11, who’s a chemistry major, so they went off to this classroom to teach science.”

Butler watched Garrett in another class as he and a DePauw student taught the meanings and pronunciations of English words.

“Patrick would act out the meaning, do anything to get them to say the word, play-acting to help them understand,” Butler says. “He just naturally fell into that engaging and entertaining approach, and I thought, This is a guy who can teach.”

Alex Avtgis ’11 wasn’t daunted by the change in plans. He’d brought books by Dr. Seuss and Shel Silverstein just in case the students didn’t have the language skills the group had expected.

“And, of course, they didn’t,” Butler says. “The way he read the books gave his students both the meaning and the rhythm of the words, and they loved it. Alex made it fun—a beautiful teacher.”

Jake German ’11 and John Funston ’10 had potential troublemakers in their group.

“They called on one of the tougher guys in the back of the room, and I thought, This is it—they’re going to have a problem now. But Jake can really draw students in. He walked down the aisle, pointed at this tough guy, the other students start laughing, and the guy goes up and does the exercise Jake was leading. The class applauds, and the guy sits down, pleased as he could be. He’d just spoken English in front of a room of 35 people.

“We were needed here in South Quito,” Butler concludes. “Volunteer teachers don’t usually go here, but if you take the College’s mission seriously, this is where you go—where there is the most need. There may also be the most danger, the most frustration, where you have to be able to deal with ambiguities, be flexible, and that’s what we wanted to put our students through, testing their mettle, testing those values.

“And their resolve won out.”

Blackboard in the Jungle

.jpg)

Professors Pittard and Hardy led the students for their next week of teaching at Yachana High School in the Ecuadorian rainforest. The school is sustained by an adjoining eco-tourism lodge, and most who come stay in the lodge or special volunteer quarters.

“Our students were the first group ever to live in the dormitory with the students,” Professor Pittard explains. And that made all the difference.

“It was so much better, both for our students and the Yachana students. They were literally immersed with them between classes, in the evenings.”

Garrett, Drew Capsalis ’10, and Chris Pearcy ’10 even helped students with their biology homework in the dorms.

“They ate together, too, and that’s where some of the best conversations took place. Our students got a bowl, a spoon, and a cup, exactly what the Yachana students got.”

Every day from 7 to 10 a.m., the Wabash students helped the Yachana students with work projects.

“Our guys just dug in and did whatever their students were doing,” Pittard says. “It was a good time for them to communicate with the students in Spanish.”

At least one student used those conversations to learn the native Quichua language.

“And this was tough work,” Pittard says. “Our guys couldn’t believe how hard the students worked.”

Pittard was impressed with her own students’ initiative.

“They really took seriously their responsibility as teachers—they were there to teach and to work. And the one-on-one sessions they had with the high-school students were great.”

The English teacher at Yachana wrote to Hardy soon after the Wabash group had left.

“I hope you all leave Ecuador more inspired to do little things in your life that change others’ lives, like you have done here. You really made a tremendous impact on Yachana.”

“There’s nothing like teaching to put to the test the things you think you’ve learned, the things you believe,” Butler says. “This was a group of students committed to making some kind of a difference, and perhaps the hardest thing for them was not knowing for certain if they had.

“They asked, ‘We only taught these kids for a week, and we’ll never see them again. How do we know if we’re doing any good?’”

In that question may be the most important lesson of the trip.

“When you’re in education, you don’t always see your impact immediately,” Butler told them. “But if you believe that you’re educating—the Latin root of the word means ‘to lead out,’ to bring people to a different place—you might be having a powerful impact you won’t see for years.

“In the end, it’s kind of a matter of faith. To be an educator, you have to believe you can reach something in someone else, something that could make a difference,” Butler says. “I think our students came to see why it’s worth it to keep on trying.”

German was a case in point as he reflected on the students he had taught in South Quito:

“They came at night because they had jobs during the day. Many worked in their homes taking care of siblings while their parents worked. Others worked in hospitals, restaurants, and clothing stores. Some worked in a factory for eight hours before coming to class.

“It was a privilege to teach such determined students.”

Photos

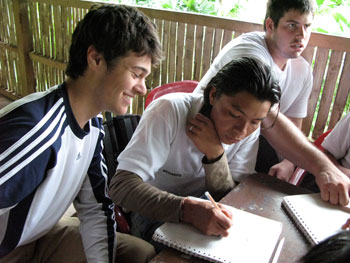

(upper right): “All of the studying that I have done at Wabash has finally come together here in Ecuador to give me a clear picture of myself as an educator and the true role that I have in a social context.”—Victor Nava ’10 surrounded by new friends in Quito, Ecuador

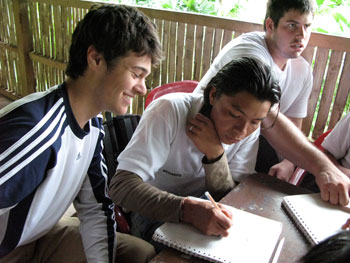

(lower right): Ian Starnes ’11 and Evan Isaacs ’10 at Yachana. Isaacs: “A teacher can prepare lesson plans all day, but you never know how ready you are until you start teaching. [Note to self: Teaching is nothing more than being flexible at all times!]”

.jpg) The lights came back on minutes later, but Butler sees the blackout, as well as the response of the Wabash men and the two DePauw women in the program, as a metaphor for this first teacher education module for the College’s Summer Study in Ecuador program.

The lights came back on minutes later, but Butler sees the blackout, as well as the response of the Wabash men and the two DePauw women in the program, as a metaphor for this first teacher education module for the College’s Summer Study in Ecuador program..jpg) Professors Pittard and Hardy led the students for their next week of teaching at Yachana High School in the Ecuadorian rainforest. The school is sustained by an adjoining eco-tourism lodge, and most who come stay in the lodge or special volunteer quarters.

Professors Pittard and Hardy led the students for their next week of teaching at Yachana High School in the Ecuadorian rainforest. The school is sustained by an adjoining eco-tourism lodge, and most who come stay in the lodge or special volunteer quarters.