In 1981, Wabash warmly welcomed its first student from the People's Republic of China—hospitality that proved an invitation not only to a College, but to a nation.

Rujie Wang ’83 expected to spend the summer of 1982 working in the College’s Lilly Library to help pay his tuition. Then Dean of Students Norman Moore called the Wabash junior—and the College’s first student from the People’s Republic of China—into his office.

Rujie Wang ’83 expected to spend the summer of 1982 working in the College’s Lilly Library to help pay his tuition. Then Dean of Students Norman Moore called the Wabash junior—and the College’s first student from the People’s Republic of China—into his office.

“He asked what I was planning to do for the summer,” recalls Wang, now a professor of Chinese and Comparative Literature at The College of Wooster. “When I told him, he said, ‘You need to get out and see America,’ and he took out $500. He asked, ‘Is that enough to travel a bit and see the rest of the country?’ I didn’t know what to say.”

A few months later, Wang, Art Howe ’82, and two friends drove to the Grand Tetons, Yellowstone, and Rocky Mountain National Park.

“We all met in Crawfordsville, rented a car, and Art drove us to these parks. It was the first time I saw the rest of America; that trip was when I fell in love with this country. I will never forget Dean Moore.”

As a member of the Red Guard, he’d been forced to denounce his father, a university professor who had attended Yale in the 1940s and had taught Chinese at Harvard to U.S. military personnel.

“The Red Guards came to our family to tell my father to confess to his so-called crimes. They kicked him and beat him up, but he insisted he had committed no crimes.

“My father told the Red Guard, ‘You need to know that America and China were allies in World War II,’ but they wouldn’t listen, because anything associated with the U.S. at that time was considered evil.”

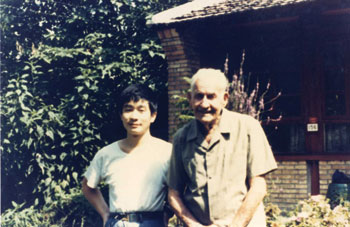

Wang’s parents taught at Peking University, where Robert Winter, Wabash Class of 1909, was professor of English literature. As a boy, Rujie had often visited “the friendly old man who had the ability to sleep while floating in the water.” As

a young man, Wang and his schoolmates would stop by Winter’s home to get a better understanding of America beyond his country’s propaganda.

“Even during the Cultural Revolution, my father had been a light for me when everyone else had been taught to hate America; I had my father to rely on, and he would say America wasn’t as bad as Mao said it was.

“Robert Winter did the same for me. I would take my classmates to visit him and he would tell us so many things about America that we wanted to know. By the late 1970s and 80s we all had so much yearning to come to the States.”

In 1978 Deng reversed Mao’s policy regarding higher education, and Wang and his generation were allowed to take the college entrance exam. Wang attended Peking Normal University for three years. Then a student in his class left

to attend college in America.

“We were shocked that this was possible. Our goal was to study so that we could eventually become high school English teachers—that’s what Peking University was all about. But by the time I left China half of my class was already in the U.S. I asked my parents if they had friends or relatives in the States, like those who had already left, but they didn’t.”

But they had Robert Winter. He wrote an impassioned letter to the Wabash Board of Trustees, including these lines describing Rujie:

“Wang is probably the best Chinese student of English that I have ever known. Since he was a child I have spoken English naturally with him and have lent him English books. In spite of his many accomplishments, his most extraordinary quality is his modesty and his quiet determination to learn.”

Wang was admitted in 1981 as a junior. When he applied for his visa at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, his interviewing

officer was Steve Fox ’69. Director of Admissions Paul Garman picked him up at the Indianapolis airport.

From Beijing’s millions to Crawfords-ville’s fewer than 15,000 residents should have induced culture shock, but the young English major found the transition relatively easy.

“I had grown up on college campuses, and I liked the Wabash campus. It seemed like a medieval monastery—people reading, writing, the study carrels in the library. I was impressed by the size of the rooms in Wolcott; I was not used to that much space and luxury. And I was drawn to the way people studied independently.”

There was one other Asian student on campus—Tomoaki Ishi ’82, now a political science professor in Japan.

“When we were homesick, Tomoaki would come to my dorm and we would cook ourselves a pot of rice and buy some tomatoes and eggs and eat Asian food,” Wang recalls. “But our American friends who drove would take us to Chinese restaurants. Coming to America was the first time I saw a buffet. That defined communism for me right there—to pay one price for everything. But I was shocked at how affluent this country was.”

Wang was most influenced by the conversations he had with faculty and fellow students outside of class.

“Tim Haffner ’82 and I had great debates in Wolcott about the political systems in our respective countries, and I enjoyed those conversations immensely. At times I would have these conversations with other students, or watch students debate everything from the Academy Awards to nudity in films. For the first time I became deeply appreciative of this culture—that there could be so many perspectives, so many ways to look at a particular issue. That was the liberal arts at work, and it affected me deeply in just my two years there.”

Wang kept up an ongoing correspondence with Winter.

“Once he wrote something I think seems almost prophetic now,” Wang recalls. “He said that China and the U.S. are so opposite to one another in their values, but there will be a day when the two countries will be friends.”

Wang remembers Professors John Swan and David Hadley counseling him when he received a “Dear John” letter from his girlfriend in China, and he has great respect for the Wabash faculty. Professor of English Bert Stern was more than a teacher.

“Bert cared about students beyond the academic, and that’s what I hope I’m doing for my students here at Wooster,” Wang says. “Bert was also interested in what China was like; he invited me to his house, and I told him about my life, working at the state-owned farm, about my parents, about Robert Winter. And he listened. There was already a space in his imagination and mind created for China.

“He was my professor, and a very good friend. I may have forgotten some of the texts he taught, but I’ll never

forget the way he approached life. And Bert’s own passion for literature and poetry stayed with me, so I brought the same passion, care, and patience when I did my graduate work.”

Wang is now a naturalized citizen of the United States.

“You are talking to an American,” he says with some pride as we wrap up our conversation. His mother lives with him in Wooster. “By now, I have spent more years in America than in China. It’s really a global community for me, the way I travel back and forth, bringing students to China.

“Home is where you have friends—I have friends there, and I have plenty of friends in the States. But I’m always traveling between languages and traditions and religions and worlds, and I feel at home with that.

“I remember Robert Winter and realize that, without his example, I would not have been able to imagine myself living in America to stay. He lived so much of his life in a country so far away, a culture so alien, yet he stayed and contributed a lot to the English department at Peking University and is still respected there. And teaching Chinese studies in America, I did the flip-side of what Robert Winter did.”

Wang still speaks fondly of his fellow students at Wabash. Their welcome was not only a college’s invitation, but a country’s.

“Greg Britton ’84 took me home to visit his family, and his father took me to his steel plant in Gary, [IN]. And John Van Nuys ’83 and his family were such loving and caring people to me. His mom once cut me a check for $120 just so I’d have money to buy clothes, and she and John’s aunt went to visit my mom in China and in Canada when she was there. All these classmates took me to their homes, into their families.

“I don’t know how I can ever repay these debts.”

Contact Professor Wang at rwang@wooster.edu

Lower Photo: Rujie Wang with Robert Winter, circa 1980