The Shiver of the Liberal Arts

Meeting in China with academic leaders, alumni, and a remarkable friend of the College, I was surprised to see anew Wabash at its best and most expansive imagination of itself.

There are many reasons for the emphasis on foreign travel and study in contemporary American higher education. Some say that we need to see the larger world in order to compete on the global stage, to understand a world that is at once incredibly large and shrinking every day. Yet the force behind the shrinking world—rapid communication and the wonders of the Internet—would seem to make a lot of moving unnecessary.

Why travel to Rome to see the Sistine Chapel when a Google search will provide images of the ceiling painted by Michelangelo in more detail than standing on the crowded floor of the Chapel will allow?

Why endure the hassle and expense of study abroad or the immersion learning experiences that have become so popular and important to Wabash students in the last 15 years? Why are these one of the four key goals of our Challenge of Excellence campaign?

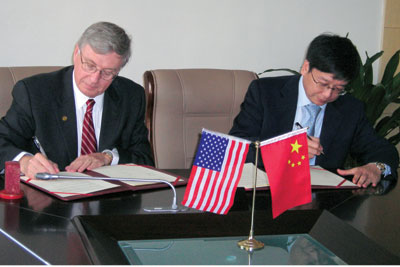

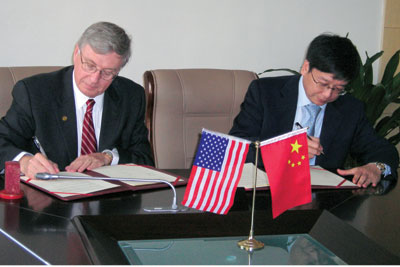

I found some answers to these questions during my own weeklong immersion-like trip to Shanghai and Beijing to meet with leaders of three Chinese universities to establish connections and explore collaboration.

I am a Midwesterner born and bred, not a world traveler like many of our faculty. For me, this trip was packed with the delight and the shock of the new. I was like a freshman on his first day on campus, ever watchful for the unusual. I developed great empathy for our students who have taken immersion trips, many even more provincial and landlocked than I. It was a feeling articulated long ago by another heartland native in a very strange place indeed: “Toto, I don’t think we are in Kansas anymore.”

This perception lies at the heart of our pedagogy for our students. The work of the Center of Inquiry at Wabash tells us that challenge and the confrontation of diversity are among the two most important factors in enhancing student learning. The shock of the new can happen in a classroom or abroad—the depth of its impact depends upon the attitude of the student and his capacity to be open and amazed. But travel is a powerful catalyst.

On our trip to China, I was challenged and amazed by new people, new friends, and new places. Yet there was another kind of wonder.

During our first full day in Shanghai, we met with representatives of Fudan, one of the greatest of Chinese universities. Dean of the College Gary Phillips and Professors Kay Widdows and Qian Zhu Pullen offered excellent presentations about Wabash and our interest in connecting to Fudan. Through alumni and friends of the College, we had been developing a relationship with Fudan for many years, but we were still moving into unfamiliar territory.

Preparing for the trip, I had encountered what I thought might be common ground. So when it came my turn to speak, I praised our hosts and the history of their distinguished university:

“I understand the name Fudan comes from a short phrase from the ancient text The Shangshu, Book of Documents, that reads, literally, ‘the heavenly light shines day after day.’ At Fudan, I understand, you take that text to mean, ‘we continue to get better.’ To me, that sounds a lot like our motto, ‘Wabash Always Fights.’”

Our hosts’ responses revealed that they saw this, too, yet seemed equally surprised. This was not the shock of the new and different, but what Herman Melville noted when he met Nathaniel Hawthorne: the “shock of recognition,” a frisson, a shiver or shudder that comes from perceiving not difference, but commonality and connection, as if you had been old friends all along.

Didn’t Dorothy return with the deep sense that many of her Kansas friends had been with her in Oz?

Some travel to find that which is completely exotic or strange, others to find something completely familiar. Both are wrong. It’s in the gap between where learning happens —the shudder of recognition you experience when you see difference where you expect likeness, when you see likeness where you expect difference. The poet John Keats called it “negative capability”—the ability to hold two seemingly contradictory things at the same time.

China is like us and not like us; we’re different, and we’re the same, and it will take the rest of our cultures’ histories to explore what that means. That’s why global education at Wabash must be an ongoing dance, not an acquisition of facts about China or wherever our students may travel.

The matter lies not in the information, but in the transformation of the life.

For the learning that comes through travel also teaches much about the traveler. Our hosts showed us new and wonderful things about Wabash as they listened and appreciated something in us that resonated with them, whether we were talking about Center of Inquiry research, global education, the liberal arts, teaching, or the Gentleman’s Rule.

As I finished a comment about the Gentleman’s Rule, Fudan Dean Fan Lizhu raised her arms in a pumping motion and said, “That’s good—we need strong gentlemen in China, as well. I’m glad someone is making strong gentlemen.”

When I mentioned that I had spent 18 years teaching at a women’s college, there was a sound of surprise, a laugh, and nods of recognition from the women leaders in the room. They began to see Wabash in a different context.

Perhaps the most moving moments of the trip came in Beijing, where we attended a conference celebrating the 30th anniversary of the China Educational Association for International Exchange [CEAIE]. Dr. Jiang Bo, CEAIE’s secretary general, had extended the invitation. He is the father of Han Jiang ’07, who was killed in a car accident in Craw-fordsville during his junior year at Wabash. Dean Phillips and I had met Dr. Jiang just days after his son’s death that spring of 2006 before either of us had officially assumed our positions at the College. We both remembered him as an unassuming man who took great pains to be gracious to us at a time of his own personal loss.

Five years later, here we were in his country.

Due to some confusion with directions, we arrived late for the conference. I intended to quietly slink into the back of the auditorium. But then we discovered that the conference hadn’t started. Dr. Jiang Bo, in effect, had said, “We can’t start without Wabash.”

We hadn’t expected to have a role in the conference, but all of the sudden we were at the center, at least in Dr. Jiang’s mind. Afterward I was telling him how sorry I was that we were late, but he wouldn’t hear it.

“That’s okay,” said this man whose experience with Wabash is tinged with a tragic personal loss. Then he spoke more formally: “You know, in me, Wabash always has a friend in Beijing.”

That evening at the lavish dinner for the conference, Dr. Jiang had invited Wabash men Hao Liu ’11 and Victor Meng ’09 to join us. Once again, he graciously brought me to the head table. As the evening progressed—with course after course of fine food and music and dance from the great professional companies of China—and as I spoke with academic leaders from China and all over the world, I came to another shock of recognition: that here was one example of Wabash at its best and most expansive imagination of itself.

When I speak to prospective students, I urge them to choose a college where they can become heroes in their own lives. The way of the hero is always moving, assuming the adventure, taking up the quest to go out of his world and return changed. For Wabash men, their four years at Wabash is a journey, a transformative experience that changes the hero and changes the lives of his family, his community, and the larger world, including the College that has a stake in his success. It is vital for Wabash and our students that our moving be as expansive and varied as possible.

T. S. Eliot writes near the end of “Little Gidding”:

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

At the heart of liberal arts education is the injunction to know thyself. This is not a task for one course, but the project of a lifetime. It is a call to keep moving, keep traveling, keep readying yourself, and this College, for the shock of the new and the shock of recognition, for all the profound and deep shivers that arise from a life of learning.

There are many reasons for the emphasis on foreign travel and study in contemporary American higher education. Some say that we need to see the larger world in order to compete on the global stage, to understand a world that is at once incredibly large and shrinking every day. Yet the force behind the shrinking world—rapid communication and the wonders of the Internet—would seem to make a lot of moving unnecessary.

There are many reasons for the emphasis on foreign travel and study in contemporary American higher education. Some say that we need to see the larger world in order to compete on the global stage, to understand a world that is at once incredibly large and shrinking every day. Yet the force behind the shrinking world—rapid communication and the wonders of the Internet—would seem to make a lot of moving unnecessary.