On Friday, April 15, a CSX freight train stopped on the tracks that cross Market Street in downtown Crawfords-ville. It was about 7:50 p.m. and traffic was backed up about a mile in both directions.

On Friday, April 15, a CSX freight train stopped on the tracks that cross Market Street in downtown Crawfords-ville. It was about 7:50 p.m. and traffic was backed up about a mile in both directions.

I know these things because I was about to give the welcoming curtain speech for the Sugar Creek Players’ production of To Kill a Mockingbird at the local community theater when the phone in my pocket vi-brated with the message, “Hold the curtain.”

Experienced directors of live theater know that holding the curtain is usually a good thing—the crowd is stacked up in the lobby and you will have a packed, if late-arriving, house. As a first-time director, I was a wreck with nervous anticipation.

I quickly sent a text message to Henry Swift and Brent Harris H’03 in the sound booth with instructions to play another piece of music to stall. And then I tried to collect myself all over again.

For six weeks I had labored with a cast and production crew of 30 through a long and sometimes difficult journey to bring Harper Lee’s story to the stage in Crawfordsville. Our production attempted to highlight the racial issues of the story—growing up poor and black in depression-era rural Alabama.

As I waited for the late arrivals behind a large set piece that formed the wall of Atticus Finch’s house, my 11-year-old daughter, Sammie, was about to take the stage as Scout Finch, a dream role for any child actor.

I’ve heard the advice they give first-time directors—“never work with kids or pets” and “never, ever direct a family member”—but somehow I didn’t think those old rules applied to me. I had second thoughts during a rehearsal in early March, when Sammie interrupted me while I was working through a critical scene with three adult actors. “Excuse me,” she said, “but could all of you make sure to recycle your plastic water bottles?” On the ride home that night I had to make it clear to Sammie that while we were at the theater, I was the play’s director first and her dad second.

For the next several weeks I wondered if I would regret choosing to distance myself from my daughter so that I might somehow seem more professional to the other actors. Had I sealed myself off from what might have been the most profound six weeks of fatherhood I might ever have?

In the shadows of set pieces that opening night, just seconds before taking the stage in her biggest role ever, she hugged me and whispered in my ear, “I’m so proud of you, Dad. I never thought you could do anything like this.” All I could muster in return was, “I’m proud of you, too. I love you.”

For all my careful study of Harper Lee’s text, it was Sammie’s unexpected embrace that opened my mind and heart to the fullness of the complicated relationship between Atticus Finch and his daughter, Scout. Kind of ironic since it was the only unplanned, unrehearsed aspect of the entire production.

Thank God for the train.

Mockingbird had never before been staged in Montgomery County. Our challenge was to produce something that did more than stir nostalgic recollections from middle-aged audiences who fondly remembered reading the book or seeing the movie as children. Our hope was that the production would inspire honest and thoughtful conversation about race and class. At the time of our play, America was celebrating the 50th anniversary of the book’s publication—but it had been only 20 years since the last KKK rally here in Crawfordsville.

I agreed to direct Mockingbird only if my friend Jerry Bowie ’04 would produce the show. I’d worked with Jerry before, and I needed him—for logistical support, rallying Wabash students to audition for a community theater play, help in building the set, and his sense of humor. But I also needed Jerry to help me understand the one thing I could never know: what it’s like to be black and suffer racial prejudice. Jerry is an African American whose roots lie in the deep south of Mississippi, but for the past 11 years he’s called Crawfordsville home.

Jerry and I made well-intentioned plans for important educational and community outreach. We received grants to go into local schools and provide free tickets to students and teachers studying the book or its themes. When the time came to visit fifth, sixth, and seventh-grade classes, Jerry and I did our best to explain the conditions of the South in the 1930s: the differences between poor white people and poor black people, and how black men were routinely, unjustly convicted of crimes they did not commit.

We had never imagined the reactions we got from the students. They didn’t get it; they couldn’t believe what we were saying. In their minds, we were teaching the stuff of legend. The kids we met have grown up in a multi-racial society, and every class we visited was rich with diversity. “But these things happened in my lifetime,” I shouted, summoning my inner Peter Frederick and seizing the teachable moment. I tried telling them that not that long ago a man with Jerry’s skin color wouldn’t have been able to teach a class in this county. Still, to elementary and middle school students, racism was something they were learning about from us—not experiencing in their lives.

That refreshing reality became another challenge for the cast and crew. We had to create the kind of environment that, as Damon Lincourt, who played Atticus, said, “would transport audiences to a different place and time,” so that the play’s enduring themes could be placed in proper context.

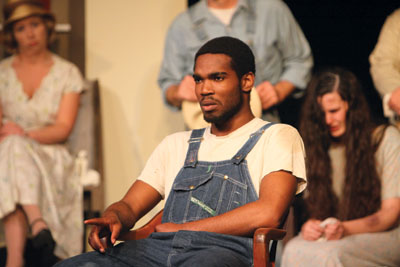

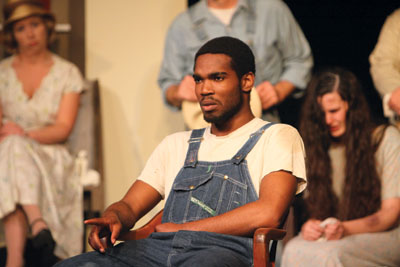

Our cast ranged in age from 11 to 84 and included Wabash students and professors, local school kids, and high-school dropouts. Some were black, some were white, and some were bi-racial. About half of the cast and crew had Wabash connections, another quarter were community theater veterans, and the others were first-time actors from Montgomery County who wanted to be a part of an historic production. There were factory workers, three grandmothers, and a Rhodes scholar (Professor Stephen Morillo deserves a Tony for the way he played the vile, racist Bob Ewell.). And two Wabash students, DeVan Taylor ’13 and Larry Savoy ’14, shared the role of Tom Robinson, the black sharecropper on trial for a rape he did not commit.

I became frustrated with the script early in rehearsals. While true to Harper Lee’s book, it was written for school and community theaters and is very much G-rated. The word “rape” does not appear in the script, and “nigger” is shouted from off-stage. Over one mid-rehearsal Sunday evening dinner, I asked the cast, “Can we help the audience better understand the ugliness of racism at that time if we replace the word ‘black’ with ‘nigger’ in a few key places in the script, just as Harper Lee had written in the original text?” A conversation not unlike a classroom discussion at Wabash unfolded, complete with references to history, culture, language, race, and politics. The actors knew that in the 1930s, a black man convicted of raping a white woman was sentenced to death (if not lynched before trial). They felt as though they needed to convey the grave consequences of our courtroom scenes. At the end of our discussion it was clear that no one was comfortable adding in Lee’s original language. But all agreed it was important to do it.

Later that night I asked Alison Aldrich, a local 19-year-old woman who played Mayella Ewell, to refer to Tom Robinson as a “nigger” in the courtroom scene. She hesitated for a long time, her lips quivering, then looked up at me and said, “I don’t think I can. I’ve never used that word before.”

It was a long process. I had to convince her that in order for our audience to understand the grievous nature of the crime and the ugliness of racism, she would have to play the part true to history. As poor, lazy, and repulsive as the Ewells were in Maycomb, AL, they were still one notch higher in that society than working black men; the only thing she held over Tom Robinson was her ability to use cruel language to keep him in his place. She managed to get the word out at each of the next few rehearsals, but she lacked the conviction to make it believable.

Two nights later, Larry and DeVan approached me and told me that they had been reading the script and comparing it with the book, and they, too, wanted to add back language. When cross-examined by the prosecutor, their character, Robinson, is asked why he ran from the scene if he did not commit the rape. The script called for Robinson to say, “If you were black like me, you’d run, too.” My Wabash actors had done their homework and knew that no African American man would refer to himself as “black” in that period. “They’d say ‘colored’ or ‘nigger,’” they explained. “Can we try the scene tonight and say, ‘If you were a nigger like me, you’d run, too’?

The students were right. Their script change was smart and gave us permission to be authentic. And over time—and with the encouragement of DeVan and Larry, two black actors on the receiving end of the slur—Alison grew into her part as Mayella.

We contrasted the insertion of the ugly language by adding two scenes to demonstrate that the black characters had lives outside the Finch home and courtroom. We showed them in their homes, raising children, and praying. We also used music to enrich our production—Billie Holiday’s haunting “Strange Fruit” set the tone at the outset of the play, and an old gospel number, “There’s a Leak in This Old Building,” suggested that justice would not prevail for Tom Robinson.

In spite of their different races and ages, the cast came together as an ensemble that could tackle the difficult issues of racism, sexism, and class differences. They came to know each other so well—and trusted each other so much—that they were capable of using the wicked language we’ve tried for generations to purge from our lexicon. DeVan and Larry, 19-year-old black men, sat on stage as a dozen white people called them “nigger” in scene after scene, rehearsal after rehearsal, night after night. Re-creating that part of our not-so-distant past was a painful, though remarkable, achievement, possible only because of the bond of trust formed within the cast.

Five months after Mockingbird closed as the most profitable production ever staged at the Vanity Theater, I was reminded that while those kids we taught in the local schools may—may—grow up in a post-racist society, there are pockets of prejudice here in Crawfordsville and, I suspect, just about everywhere.

Dr. Willie James Jennings is a professor at the Duke University Divinity School and visits Wabash every few months as a member of the Advisory Board for the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning in Theology and Religion. On September 10, 2011, he was on campus for a series of meetings, and late that afternoon he decided to walk a few blocks to the local CVS pharmacy. Dr. Jennings is an ordained Baptist minister, prolific writer, and esteemed scholar. He is also African American.

As he made his way from the Wabash Center to CVS, a truck pulled up beside him and slowed down. The passengers shouted at him, ridiculed him, and called him “nigger.” Shocked by the verbal assault, Dr. Jennings’ first instinct was to reach for his phone to take a picture of the license plate. But because he was alone—and fearing physical assault—he chose not to take the photo. He kept walking. Before he got to CVS, another car drove past him and a passenger leaned out the window and made a rude gesture.

Hearing of the events two days later, I was speechless—sucker-punched back to reality. And those events reinforced in my mind that the play we staged and the environment to which we attempted to transport our audiences was not the stuff of legend. We still have a long way to go.

Mockingbird has been described as one of the great children’s books of all time. Yet its themes are hardly typical childhood fare, and there is no happy ending. Tom Robinson is found guilty—though even the prosecutor knows it’s a sham—and is shot dead in prison not long after. Bob Ewell continues to walk the streets spouting racist garbage and is later killed by Boo Radley, the white recluse who is never charged or brought to trial. Harper Lee taunts readers with the notion that Maycomb is making “baby steps” toward basic human rights. She also makes it clear that meaningful progress will take generations.

That progress won’t happen, as Atticus Finch says, until we consider things from the other’s point of view, until we “climb into his skin and walk around in it.” Perhaps what made our production so successful was our ability to do just that. As teachers, we saw a new multi-racial world through the eyes of the kids in our local schools. African-American actors, dis-covered new pieces of their own history, and helped to educate the cast and our audiences. White actors came to feel the bitter sting of racism. Wabash students gained an appreciation of the power of community theater and the hard work it takes to sustain it. Local actors, veteran and novice, came to see Wabash’s students, faculty, and staff quite differently.

And parallel with the story’s central relationship between Atticus and Scout, one father got to see himself through the eyes of his daughter, and one daughter came to know her father as someone other than the guy who does PR for Wabash.

Thank God for the train.

Top Photo: Larry Savoy '14 as Tom Robinson

On Friday, April 15, a CSX freight train stopped on the tracks that cross Market Street in downtown Crawfords-ville. It was about 7:50 p.m. and traffic was backed up about a mile in both directions.

On Friday, April 15, a CSX freight train stopped on the tracks that cross Market Street in downtown Crawfords-ville. It was about 7:50 p.m. and traffic was backed up about a mile in both directions. Mockingbird had never before been staged in Montgomery County. Our challenge was to produce something that did more than stir nostalgic recollections from middle-aged audiences who fondly remembered reading the book or seeing the movie as children. Our hope was that the production would inspire honest and thoughtful conversation about race and class. At the time of our play, America was celebrating the 50th anniversary of the book’s publication—but it had been only 20 years since the last KKK rally here in Crawfordsville.

Mockingbird had never before been staged in Montgomery County. Our challenge was to produce something that did more than stir nostalgic recollections from middle-aged audiences who fondly remembered reading the book or seeing the movie as children. Our hope was that the production would inspire honest and thoughtful conversation about race and class. At the time of our play, America was celebrating the 50th anniversary of the book’s publication—but it had been only 20 years since the last KKK rally here in Crawfordsville.