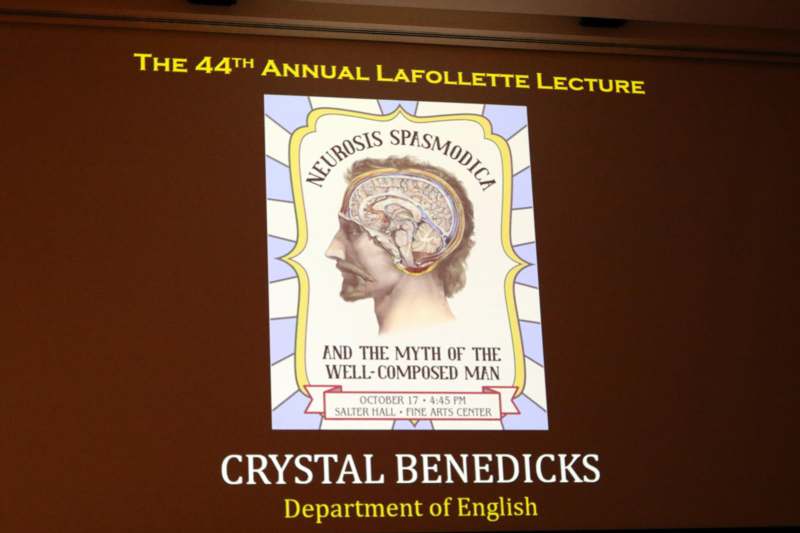

44th LaFollette Lecture: Crystal Benedicks

The LaFollette Lecture series was established in 1982 by the Wabash College Board of Trustees to honor Charles D. LaFollette, their longtime colleague on the Board. The lecture is usually given annually by a Wabash College faculty member who is asked to address the relation of their special discipline to the humanities, broadly conceived. This year's lecture, “Neurosis Spasmodica and the Myth of the Well-Composed Man,” was delived by Crystal Benedicks, Associate Professor of English. Presented with the accompanying photos are excerpts from her lecture.

Crystal Benedicks teaches writing, poetry, and a range of literature classes. Her research interests include Victorian poetics, composition theory, queer theory, and masculinity studies. Her most recent research project examines the legacy of the “Spasmodic” poets, a group of 19th-century writers who were laughed out of the literary canon because of their strange, excessive verse.

As the coordinator of the College’s efforts to teach expository writing, Prof. Benedicks takes a special interest in teaching composition courses at all levels, from introductory to advanced. She believes that writing is at the heart of a liberal arts education, and she enjoys the opportunity to work with Wabash students on honing their abilities.

"Today I want to talk about the intersection of three fields that have structured my academic career: literary studies, disability studies, and the teaching of composition," she started. "I invite you to explore with me the ideas we’ve inherited about what good writing is and what proper bodies are."

"The finished essay, the final draft turned in to the professor or the articles professors send out for peer review, we like for them to portray us, even if implicitly, as more whole, more cohesive, braver, than we are," she said. "Indeed, why not? Isn’t that how you maintain a good GPA or get published? Isn’t that what I’m trying to do here, on this stage? We might not have a century of cheerleaders congratulating us on our Byronic prowess when we write something good, but we do feel good when people describe our writing as 'strong' or 'powerful' or 'masterful.'"

"What I want to do today is try to get at that associative link between writing and shame," she said. "I want to pull apart those stories about Byron and Dobell to figure out why they seem to serve as elaborate smokescreens for Byron’s disability. That is, I want to think about how sound bodies got linked to sound texts and how shame fringes our efforts to conceal our flawed selves with unflawed writing.

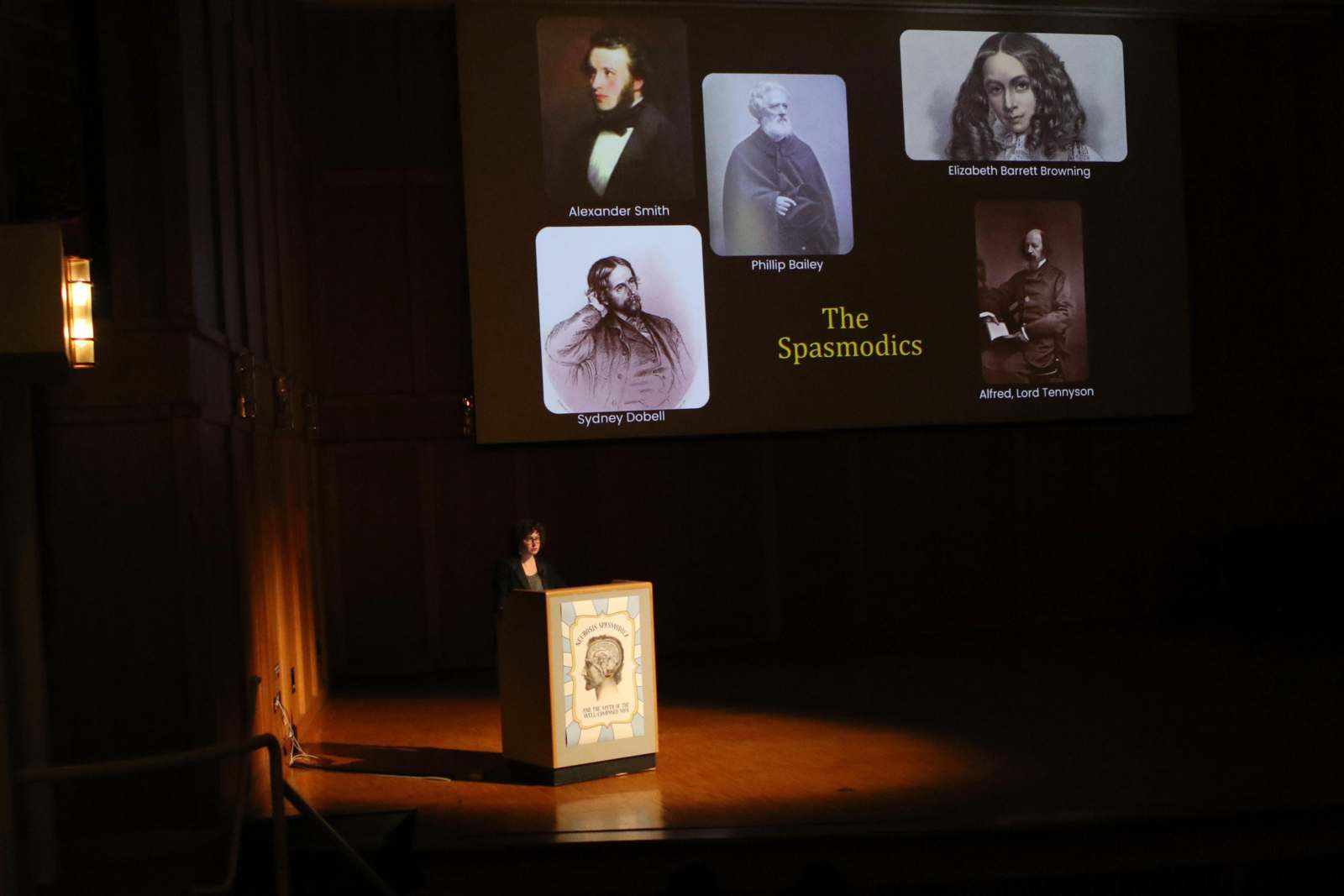

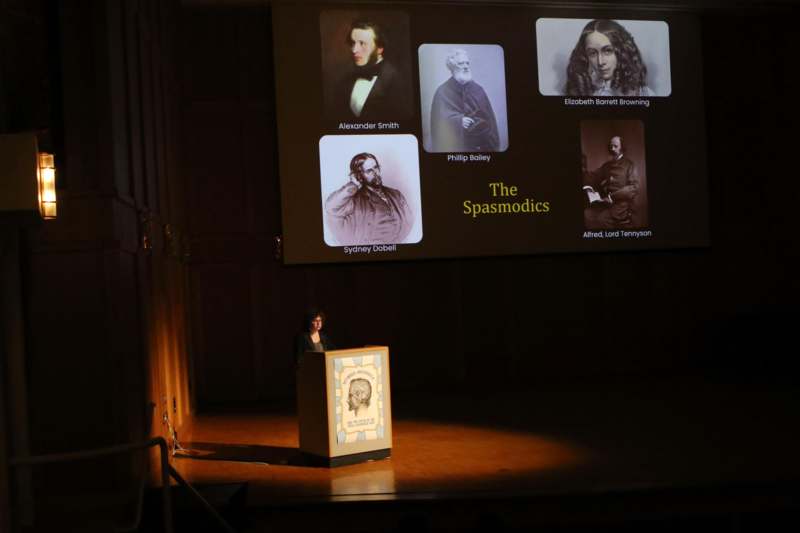

"To do that, I want to turn again to the 19th century and describe the school of poetry to which Dobell belonged: The Spasmodics. The most notable Spasmodics were Sydney Dobell, about whom I’ve spoken, Alexander Smith, and Phillip Bailey. Even such luminaries as Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote poems many considered 'Spasmodic.' They were a group of loosely associated poets who rose to considerable fame in the 1850s. A 19th century literary magazine claimed that Spasmodic poets 'received a more universal and flattering welcome than was ever before awarded to an English poet.' Spasmodic poetry evoked intense emotional states using unusual, dazzling images and irregular meters. Their book-length poems often dwelt in detail—something like seven thousand lines of detail-- on a lonely, tormented speaker’s plight."

"Most people’s experience of writing is closer to the creative and personal and even sometimes tormenting practice of the Spasmodics and further from the bravado and machismo of the military general," she said. "We already know the toll it can take on mental health to be told that one must be in control at all times. And aren’t there more productive metaphors for the creative task than to subdue and dominate? What about exploring, questioning, proposing, striving? The creative endeavor seems to me so far removed from the clamped-down rigor of the dutiful warrior."

"It wasn’t only bodies that could go Spasmodic, either," she said. "In the 1860s, medical researcher Henry Maudsley describes a type of mental illness he calls “Neurosis spasmodica,”a condition in which a person is “liable to whimsical caprices of thought and feeling; and, although he may act calmly and rationally for the most part, yet now and then his unconscious nature, overpowering him and surprising him, instigates eccentric or extravagant actions.

"Critical discourse about Spasmodic poems and medical discourse about spasmodic bodies are both marked by panic about losing control. In the Victorian medical imagination, spasms marked the difference between a knowable body and a radically disconnected one; a body that was almost outside the realm of meaning. When literary critics employed the term 'Spasmodic' to refer to poetry, then, they were impugning more than style. They were facing the painful and always unanswered question of whether or not people can control or know their own bodies or minds. The implications were as threatening to notions of physical and mental fitness as they were to notions of masculinity and purposeful writing."

"We here in this room may know more intimately than most how gentlemanliness, as a concept, is often illusive, that living up to it takes time and effort," she said. "You don’t become a gentleman just through the desire to be one, any more than a clear cogent thesis is the first thing to appear in a writer’s mind. We work at these things. It’s important to remind ourselves that gentlemanliness, like clear writing, is always an evolving process. Progress is a result of failure; drafts are never finished. We also know that a restrictive definition of gentlemanliness, this old-fashioned Victorian one, with its insistence on fierce domination—is an impossible standard of masculinity with no room for empathy, retrospection, vulnerability, rest, or human connection. This version of the gentlemen has sent so many men to their graves.

"But we don’t have to accept that as our collective definition of what gentlemanliness means today. We can shed the gendered straitjacket it implies, remove both the idea of the writer and the idea of the gentleman from their roots in an exclusive system of gender, race, and class privilege. We only invite more voices in when we recognize that efforts to develop, as people and as writers, are more important, in and of themselves, than the seamless finished product. What would this free up in us? What kinds of approaches to self and creativity would it allow?"

"Today the relationship between what poetry can teach and what composition students need to learn is often occluded by the sense that poetry is emotive and subjective while prose (especially college writing) is thoroughly logical," she said. "We can see the seeds of this attitude in the 19th century. Just as many composition handbooks today emphasize correctness over emotive power, the typical Victorian writer’s guide would begin with the grammatical ordering of words in a sentence, proceeds through sentence structure, the ordering of sentences in a paragraph, and the ordering of paragraphs in a whole paper."

"This desire to keep order is exacerbated by the chaos it was intended to banish, a chaos that was rooted deeply in the nervous system and which shared a name with a strain of evocative poetry: Spasmsodicism," she said. "That frightening slip from control. Writing has long been associated with the projection of strength. In her book Writing: Gender, Rhetoric, and the Rise of Composition, writing theorist Miriam Brody argues that throughout the history of composition, from antiquity to today, 'good' writing has been equated with traditionally masculine values of mastery, force, restraint, and simplicity."

"All of this depends, though, on the assumption that the quality of the writing measures the quality of the man—but that’s too simplistic an equation," she said. "Writers don’t pin their already-digested ideas down on paper; they create those ideas through a restless, endlessly fecund engagement with words that hone thinking and thinking that hones ideas. The writerly self isn’t a projection of mastery or of anything else, it isn’t an a priori moral avatar, it’s a always-developing production of the dance among thinking, writing, rewriting, rethinking."

"We can emphasize writing as an iterative act of self-and-world creation, but we are working within powerful cultural forces that reward seamless mastery and self-control. Think of Byron bolstering his poetic worth by physically parting the waves. That is, it’s OK—even noble—to struggle through the writing process as long as you win in the end, make it to the other side of the Hellespont and wait for your praise. It may be that the only way to create an essay that looks and sounds clear, cohesive and controlled is through uncertainty and grappling, but when we cast this journey as a quest for mastery, we imply that the anxiety and unpredictability of writing are necessary demons to be conquered along the way rather than evidence of the hard thinking writers do."

"To be clear, I’m not suggesting that we all start writing like Spasmodics," she said. "I don’t want us to toss out thesis statements and organizing principles and cohesive writerly personas. I want instead to see those as something hard-won, so that when we experience confusion or anxiety, we don’t see ourselves as failing, but as engaged in some of the deepest work we do at colleges—writing. It’s a deeply human task—perhaps because it takes a long time and it is difficult. I think Spasmodic poets alarmed their hostile critics because they acknowledged and even celebrated that difficulty, rather than pretending that composure ever comes easily. They didn’t want to hide the inelegant parts of creativity—and nor do I. We can help students write better—and write better ourselves—when we acknowledge that cohesive, graceful prose is nobody’s first language."

"My studies of the Spasmodics has led me to a field of inquiry that emphasizes these lived relationships: that is, disability theory," she said. "When critics used the pathologized medical language of “spasms” to describe a school of poetry, they were in effect rendering it disabled. Calling something “disabled” is an effective way to render it invisible, but the link between Spasmodics and disability also provides a critical lens through which to see them and to probe the ideas about writing we’ve inherited from the controversy over them."

"I wrote about the Spasmodics for years before I figured out I was thinking about my mother," she said. "I can see now that I transposed into literary studies the issues of shame, disability, writing, and even pleasure that were central to her real life. I suppose I wanted to sanitize and distance myself from those things—maybe as a way to give me room to grapple with them. Maybe all writing has some element of the repressed, the personal, the child’s longing to understand."

"Her disability created profound physical intimacy—at times, all of us in my family were extensions of her body, executing the commands her broken nervous system could not," she said."It’s my hope that in supporting one another in tasks physical and academic, as mundane as pulling a lever or as significant as helping direct the leadership of the nation, as simple as making an appointment at the writing center and as profound as allowing ourselves the space to make a creative mess, we can become freer and better writers and citizens, with an appetite for risk and a dedication to the working out of our ideas, just as we become more able to value the ways our lives are essentially and powerfully entwined. We can see that calls for mastery and domination of self and of our productions are rooted in shame and fear. And we can choose instead the radical honesty of owning how consuming our work is and honoring the points of human connection that enable it."