MOTIVATION AND INSPIRATION

Some view classical liberalism as but one political philosophy amidst many alternatives. Whereas an egalitarian would judge the moral qualities of a community with reference to its distributions of power and privilege, the liberal cares most about the levels and potentials for individual rights and freedoms. Yet, classical liberalism transcends the disciplinary confines of political philosophy.

It instead draws from and also bears relevance upon the entire array of social sciences and humanities. As twentieth century economist, Ludwig von Mises (1927) perhaps noted best, “Liberalism is not a completed doctrine or a fixed dogma. On the contrary: it is the application of the teachings of science to the social life of man.”

Freedom is not just a goal or evaluative standard of society, it is perhaps the most explanatory variable in all of human history and social science. Ebbs and flows in the levels and qualities of human liberty arguable coincide with the existence and flourishing of civilization itself.

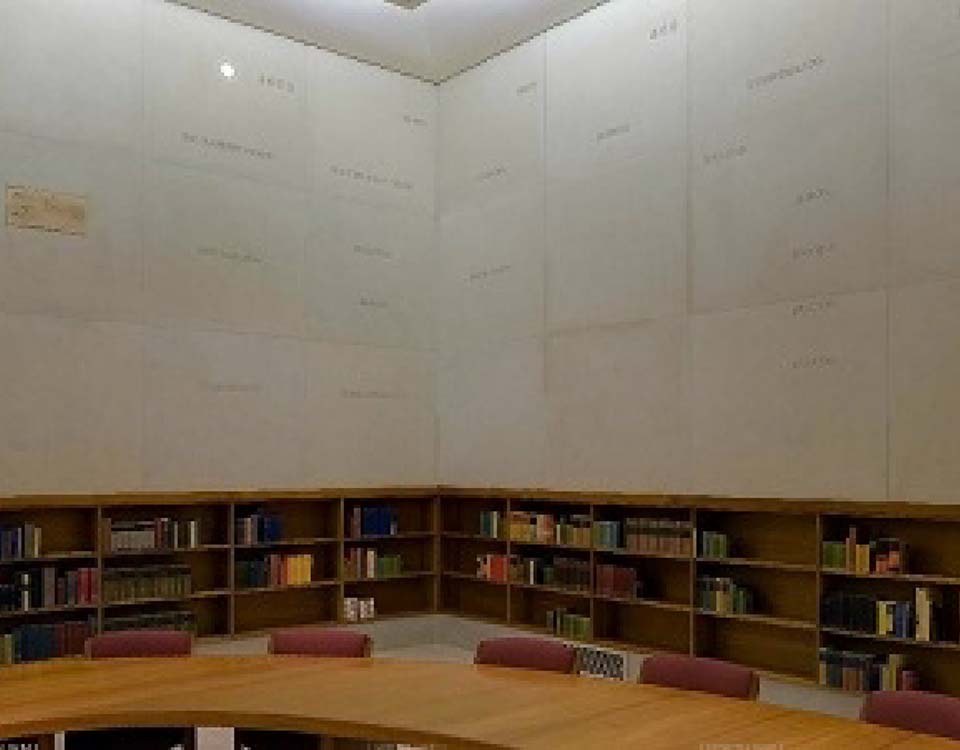

Wabash alumni, and renowned philanthropist Pierre Goodrich shared this educational vision of the liberal tradition as it is embodied in the architectural design and décor of the seminar room on Wabash’s campus which bears his name.

“Etched into limestone slabs set in its walls are important names and developments of significance in the history of freedom that stretch back in time from the Declaration of Independence to the epic story of Gilgamesh...

Beneath the limestone inlays Mr. Goodrich placed the primary works and histories of each entry plus other writings that have contributed significantly to our understanding of liberty. The collection of books thus extends the story of humankind’s struggle against tyranny well beyond the Declaration of Independence and into the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In the middle of this vast collection of materials is a large oval table that can be broken down into smaller stations to accommodate conversation groups of various sizes. When one considers the room as a whole, the intent of its designer becomes evident: the idea of liberty, which was developed and transmitted from generation to generation, is seen as a long historical conversation of which the students themselves are a part (Eicholz 2000).”

Since the enlightenment era, Max Weber was a pioneer of modern sociology. Adam Smith is the proverbial founding father of economic science. Alexis de Tocqueville deserves similar credit for some of the earliest developments of political science. And, nary a philosopher can deny the lasting influence of Emmanuel Kant or John Locke on philosophy today. These thinkers each made foundational contributions and essentially launched wholly distinct fields of study academic inquiry. Their shared identities and commitments as liberals were not a mere coincidence.

One could argue that given liberalism’s inter-disciplinary relevance, the classical liberal tradition carries strong implications for a wholistic vision of a liberal arts education. But what is the status of classical liberalism in higher education today?

Academia of the late 1960s hosted a healthy mix of diverse perspectives regarding political philosophy and public policy. Approximately 45% of faculty self-identified as left-leaning, 29% as right leaning, and 29% as moderate. Today, more than 60% identify on the left, 30% as moderate, and merely 10% as conservative. Some disciplines consistently report zero self-identified classical liberals when surveyed. This asymmetry is more pronounced in the northeastern elite universities, and it is similarly more pronounced within the humanities departments and administrative roles of higher education relative to the natural sciences and professional disciplines (See: Brennan and Magness 2019).

Today’s undergraduate students may never have the opportunity to take a course that focuses explicitly on the themes or topics of classical liberalism. In so far as college courses do engage ideas like individual liberty, personal responsibility, private property rights, the Scottish Enlightenment, America’s constitutional founding, and free market economics; it is becoming less and less likely that such a class will be led by a faculty member who finds such ideas compelling, or whose own research aims to progress the classical liberal tradition.

John Stuart Mill (1859) famously argued that students are at a great loss in this state of affairs. Not only is the engagement with opposing arguments important for understanding one’s own position, but a student, “must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them; who defend them in earnest, and do their very utmost for them. He must know them in their most plausible form; he must feel the whole force of the difficulty which the true view of the subject has to encounter and dispose of, else he will never really possess himself of the portion of truth which meets and removes that difficulty.”

With Mill and all of the above in mind, the Stephenson Institute has designed a seminar model to provide motivated undergraduate students with a week-long intensive opportunity to read, learn, and discuss the substantive intellectual contents and contributions of the classical liberal tradition. We have selected core texts as associated readings, chosen dedicated lecture topics, invited renowned faculty experts, and scheduled opportunities for group discussions and debates.

We hope that any and all undergraduates wanting and interested in deepening their working knowledge of the ideas and research associated with classical liberalism and the free society feel inspired to apply. All are welcome to apply, but space is limited.

SOURCES

Brennan, J. and Magness, P. (2019). Cracks in the Ivory Tower: The Moral Mess of Higher Education. Oxford University Press.

Eicholz, H. “Forward” in P. Goodrich (2000). The Goodrich Seminar Room at Wabash College: An Explication. Liberty Fund.

Mill, J. (1859). On Liberty. John W. Parker and Sox, West Strand.

Mises, L. (1927). Liberalism: The Classical Tradition. The Ludwig von Mises Institute.

SHARE PAGE